Should we be afraid? The coronavirus is the subject of all our conversations, not news bulletins without counting the sick, the dead, the measures taken by this or that government. To stop, if not eradicate, what seems to have become a strange paranoia with unpredictable consequences. Locking up cities, fencing more borders, sending children out of schools, all these coercive measures are coercive measures that the world has not seen for a long time; perhaps never, at this point of globalization where we are. The doctors who are monitoring this epidemic coming from China have been trying, in recent days, to be reassuring. But the damage already seems to have been done: fear has set in, and its procession of collateral damage has put economies on the back burner.

Great fears are a leitmotif in history, almost always carried by epidemics. An evil, whose origin is often unknown, strikes blindly and kills en masse. The Aztecs who were decimated by smallpox, like the plague-stricken people of the Middle Ages, found a divine origin for the evil that struck them. A vengeful anger to punish men. When they are not gods, they are scapegoats that men will look for to explain the inexplicable. Jean Delormeau in his masterpiece Fear in the West has observed it well. The foreigner, the Jew, the Gypsy, the Spaniard... was pointed at and raised as an outlet for fear.

Great means and strong method

The coronavirus epidemic occupying the world has its source in China. A mysterious country, so far from us in all respects, an immense country to which ogre appetites are readily attributed, this Middle Kingdom populated for most of us by immense shadowy areas, from this country the virus arrived at the end of the year 2019. This birthmark of the coronavirus, moreover, in the gloomy wildlife markets of a province whose name no one knew, this virus transmitted to a few consumers of bat soup, no more mysteries were needed for the unbridled fear to take hold in the minds.

The Chinese government was the first to be confronted with the epidemic and immediately reacted with great means and a strong method. An entire province and its sixty million inhabitants quarantined, hospitals built in a few handfuls of days, armies of scientists flooding the world with studies and research, an unprecedentedly rapid identification of the virus, its sequencing made available to all the biologists on the planet. All these exceptional actions converted into strong images on all the world's television channels and social networks, which forged the idea that this was serious business. This virus is highly dangerous.

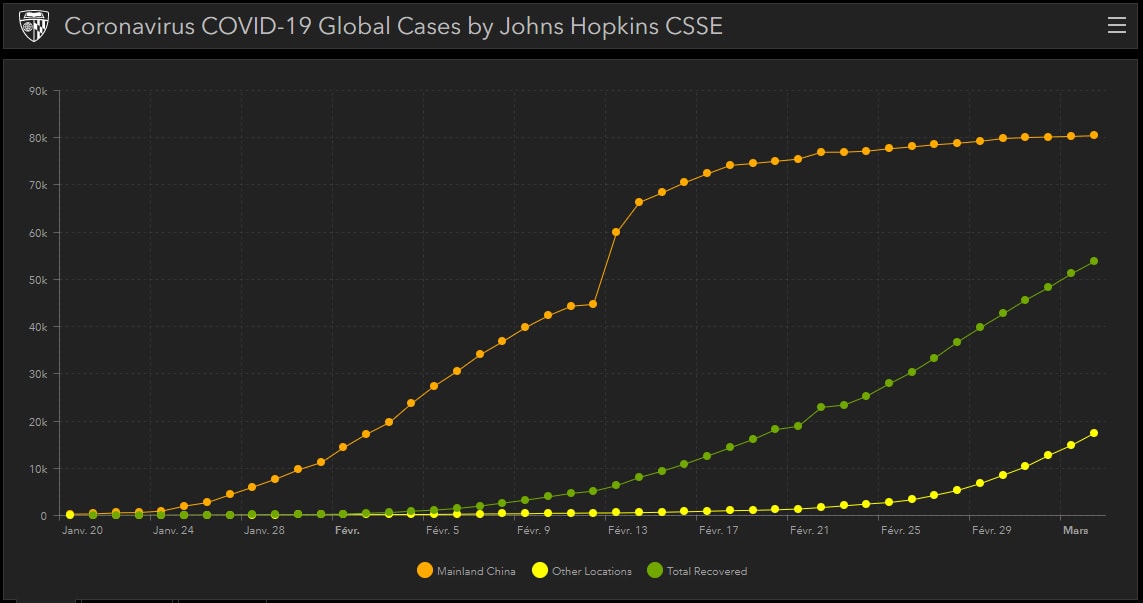

This may be true, and we don't yet know for sure, but if doctors agree that coronavirus is a serious threat, they are rushing to add that the disease it causes, the notorious COVID-19, is actually not that dangerous. One hundred thousand cases have been reported worldwide to date, and just over 3,000 deaths, including 2,912 in China and less than ten in France. The figures counting victims are always a little obscene because they do not reflect the personal, human tragedies. They are curves, Excel spreadsheets, statistics, and considered thus, disembodied, they serve conveniently for comparison. As such, a banal seasonal flu kills every year, according to theWHO,between 300,000 and 650,000 people in the world, including an average of 10,000 in France. We are far, very far from the coronavirus accounts.

Morbid accounting

Especially since the coronavirus counts are not crystal clear. Scientists have calculated a case-fatality rate that seems questionable. This rate is the result of the ratio between infected persons, identified carriers of the virus, and those who succumb to the disease. For the rate to be accurate, both components of the equation must be accurate. As for the number of deaths, there is no problem, they are easily identified. However, the mystery is getting thicker every day in terms of the people who are infected. We discover, in fact, that it is possible to be a carrier of the virus without declaring the slightest symptom; these are the healthy carriers. There are therefore believed to be many more infected people circulating in the world than the number of people who are reported to be infected, which obviously changes the result of the case-fatality rate.

The other questionable rate is that of morbidity, i.e. the number of patients in relation to the total population. It would be 100,000 people in the world today. A figure that must be related to the 7.7 billion people who populate our globe. As a reminder, the Spanish flu that struck in 1918 affected between 30 and 50 % of the world's population.

If we stick to the numbers, the coronavirus should in no way trigger a wave of paranoia and panic.The opposite is true. To protect themselves from evil, societies are digging up their old recipes, such as quarantines - which have become fourteen - the closure of schools and universities, bans on gatherings, shows, crowds, etc. There is talk of closing borders, of wearing badges to distinguish the sick from the others, of postponing elections, and perhaps even the Olympic Games. Some states are innovating, as in China, and are using artificial intelligence, personal data management and the most sophisticated biometric controls, with Orwell called upon to track down the coronavirus. Protective masks are stolen, biocidal products are ruthlessly used to wash hands, supermarket shelves are looted to stockpile in case...

Most of these measures are intended to delay the spread of the virus, experts say, but are putting whole sectors of the economy on the sidelines. Stock markets are in a panic, businesses are worried, consumers are clamouring to stay away from bars and restaurants, and every trip seems like an extreme adventure.

That fear that feels good

Widespread paranoia that speaks volumes about how our societies view risk. We want to protect ourselves from all risks and, as a precautionary principle, we demand the maximum protection in the face of uncertainty. We barricade ourselves. The preventive measures we could take, such as vaccines or stockpiles of drugs, are useless because we have no vaccine or drugs. So we take action to protect ourselves against what could happen. The discrepancy between what the official messages tell us - Wash your hands! - and the highly technical nature of the biology labs looking for a vaccine or a cure is abysmal. The public knows that the brilliant scientists in our research labs will eventually find the answer. But in the meantime, we are in danger of dying and the only protection they offer us is not to shake our hands, not to give us kisses and to wash us every hour with a hydroalcoholic solution. A gap which cannot fail to feed all forms of anxiety if not fear.

Maybe we want to, and maybe that fear does us good.We live in a world that we are told is dangerous, that it may collapse; disasters are just around the corner and the sky will inevitably fall on our heads. With the coronavirus, we have something concrete. Real, solid. Real, real, scary danger. The Italian philosopher Sergio Agamben thinks, in a column, that this fear, which has been lurking in the depths of our consciousness for some years now, finds here a way to translate it into a state of collective panic. This is not just a pretext or an outlet; it is also the entry into an extremely perverse dimension where we would be ready to restrict our freedoms in the name of this fear.Inspection mission

What has happened in China is very exemplary in this respect. A few weeks ago, hospital beds in China were overflowing with sick people. We all have in our minds these images of the hasty construction of a huge hospital in Wuhai. China was overwhelmed by the massive influx of victims of the virus. The rest of the world was worried.

What's happening today? Beds in Chinese hospitals are almost empty. Doctors are having trouble finding patients to conduct clinical trials of their new drugs. The number of cases of coronavirus patients has dropped dramatically.

It's not the Chinese who say so, it's the WHO experts who reported on their inspection mission on February 28. The decline in the cases of COVID-19 is very real.

This report comes at a critical time in what many epidemiologists now consider a pandemic. Last week, the number of affected countries rose from 29 to 61. Several countries have found that they already have a community-wide spread of the virus - as opposed to only travellers from affected areas or people who were in direct contact with them - and the number of reported cases is increasing exponentially.

The opposite has happened in China. On 10 February, when the preparatory team for the joint WHO-China mission began its work, China reported 2,478 new cases. Two weeks later, when the foreign experts packed their bags, the number had dropped to 409 cases. (Yesterday, China reported only 206 new cases).

The experts of the WHO international mission visited hospitals, laboratories, businesses, markets selling live animals, railway stations and local government offices. They also examined the huge body of data that Chinese scientists have compiled. They learned that about 80 % of the infected people had mild to moderate disease, 13.8 % had severe symptoms and 6.1 % had life-threatening episodes of respiratory failure, septic shock or organ failure. The case-fatality rate was highest in people over 80 years of age (21.9 %) and in people with heart disease, diabetes or hypertension. Fever and dry cough were the most common symptoms. Surprisingly, only 4.8 % of those infected had a runny nose. Children accounted for only 2.4 % of cases, and almost none were seriously ill. Mild and moderate cases took an average of two weeks to recover.

Agility and aggressiveness

Much of the report focuses on understanding how China achieved what many public health experts thought impossible: containing the spread of a widely circulating respiratory virus. The most dramatic - and most controversial - measure was the lockdown of Wuhan and the "China has deployed perhaps the most ambitious, agile and aggressive disease containment effort in history."neighbouring towns in Hubei province, which has placed at least 50 million people under mandatory quarantine since 23 January. This measure has " effectively prevented any further export of infected persons to the rest of the country" concludes the report. In other parts of mainland China, people have been voluntarily quarantined and monitored by designated officials in neighborhoods. In Wuhan alone, more than 1,800 teams of five or more people have traced tens of thousands of contacts.

Aggressive "social distancing" measures implemented across the country included the cancellation of sporting events and the closure of theatres. Schools extended the holidays that began in mid-January for the Lunar New Year. Many businesses closed down. Anyone going outdoors had to wear a mask.

Two widely used mobile phone applications, AliPay and WeChat - which have replaced cash in China in recent years - have helped enforce restrictions, as they allow the government to track people's movements and even prevent people with confirmed infections from travelling. " As a result of all these measures, public life is very limited." notes the report. But the measures worked through a combination of " good old-fashioned social distancing and highly effective quarantine with this neighbourhood-level field machinery, facilitated by big data and AI "

China did not hesitate to implement exceptional measures in the face of a threat that was shaping up to be exceptional. The result seems to be there. But can this Chinese model be exported elsewhere? Nothing is less certain. Indeed, it is accepted that China is unique in the sense that it has a political system that can make the public obediently comply with extreme measures. « No one else in the world can really do what China just did.". Nicole Teke, spokesperson for the French Movement for a Basic Income (MFRB), created in 2013, explained à la revue Science magazine.

Learned balance

In response to the fear of coronavirus, Western societies are implementing risk reduction measures. It is a strong demand from their populations worried about the speed of the virus' spread, but it is also the search for a skilful balance between cost and necessity.

Faced with one risk, companies shift the problem to another riskThe German philosopher Niklas Luhmann taught us in his sociological theory of risk that the solution to a problem consists in moving it from one subsystem to another, from one functional sphere of society to another. In this case, it is a question of transforming a health risk, here into an economic cost, and there into an impact on human rights. Faced with a risk, societies shift the problem to another risk that may have equally or even more serious consequences. This inevitably displaces or even increases the scope for paranoia.Beyond fear, what the coronavirus reveals to us is the agility with which it has settled into our lifestyles, our daily lives and our perceptions of the world. Tens of millions of people around the world have learned new patterns with incredible speed. Teleworking and teleconferencing have taken hold in the world of work; economists are taking a new look at the logic of value chains and just-in-time flows advocated by globalization, and are giving velvet eyes to short circuits and the relocation of production circuits. Didn't the Minister of the Economy recently saythat the coronavirus was a " game-changer" in this matter?

The imposed "social distancing" will undoubtedly create a gap that will deepen if the crisis continues. But won't this lack, this deprivation bring out the richness of real exchanges and contacts between humans? So many feelings that seemed to be forgotten, competing with a vain greed in consumption.

The ongoing pandemic has also taught us and raised our intimate awareness of the porosity of the world. The virus has crossed all borders, it has taken hold in all societies, regardless of their lifestyles, religion or political colour. All are equal in the face of the virus as we are in the face of the CO2 particles or heat waves that threaten us. The coronavirus shows us how much the world is a physical place. Perhaps we had forgotten it a little, drowning in our screens, our virtual networks and the artificiality of our living places. We had forgotten that we had a lot of control until we no longer had it. And that moment can come quickly, very quickly. Reality, whether it is a virus or a climate crisis, is capable not only of scaring, but of biting.