Since its appearance, the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19 has been the subject of an avalanche of scientific studies and research. More than 50,000 articles have already appeared in medical journals in just four months. Let us remember that last December we did not even know the name of the virus that has become the object of concern for all the inhabitants of our planet. Entire battalions of scientists, researchers and doctors from all countries are totally tense on this subject: to sequence the virus' genome, to find a vaccine, a treatment, to understand its dynamics, its contagiousness, the physiological damage it causes to the sick, etc.

Governments around the world rely on these scientists to implement protective measures, to order containment and de-confinement. Yet the impression of a hesitation waltz remains. For the uncertainties persist and this damn coronavirus raises questions, often fundamental ones, that scientists are still stumbling over.

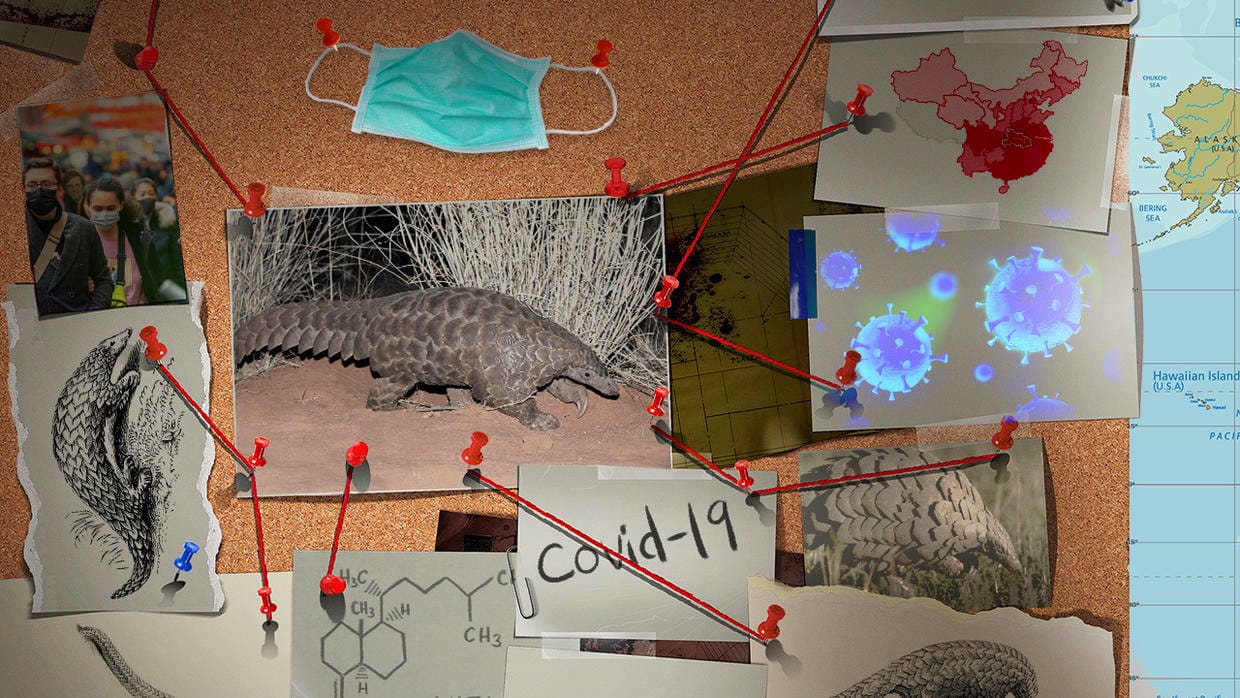

Where did he come from?

Where did he come from?

That's the first riddle. It is not only of interest to historians who want to trace the origins of what has world upheaval in these few weeks of the early 2020s. It is of great interest to epidemiologists who want to know so that this does not happen again. It is known that it was born in China, and that its genome bears an uncanny resemblance to that of the coronaviruses that used to infect bat populations. For lovers of strange signs, note that the exact anagram of "bat" is "strain-to-virus "*. Coronaviruses like these gentle mammals and colonize them without much damage because these bugs have developed, over the course of evolution, adapted immune defences.

The big question is how could the virus jump from one species to another, from bats to humans? We suspect an intermediate host. From the beginning, we suspected pangolin was the ideal candidate for this intermediary. But the hypothesis is tending to be abandoned. Today, we're not sure of anything. We don't know if the virus jumped from bats to humans, if it mutated to do so, if it used another vector. These are all questions that will have to be answered if we are to avoid further pandemics caused by our encroachment growing up in the wilderness.

How is it transmitted?

How is it transmitted?

It's the question of the century. And at the time of writing, and contrary to what all the containment measures or barrier measures put in place around the world might suggest, not much is known. More than two million people-at least-are officially contaminated around the world. How were they infected? Specialists believe that this type of virus causing respiratory diseases is transmitted by coughing, sneezing, through a multitude of droplets projected by an infected host. Everyone has learned that it is the sputum that transmits the virus. But not much is known about transmission through fomites. These are the surfaces likely to be contaminated. Several studies have been published measuring the life span of the virus on cardboard, plastic or metal. In reality, nothing is certain, including how long a virus can harm a surface.

It is also questionable whether aerosols may play a prominent role in transmission. These are clouds of invisible droplets projected into the air by an individual carrying the coronavirus. Finnish scientists have established that these clouds can remain airborne for several minutes. This would be a highly contaminated environment, favoured in confined spaces, with many people, poorly ventilated.

A good understanding of how the virus is transmitted is fundamental to defining truly effective recommendations and modes of conduct. For the time being, the question remains unanswered.

What's his actual mortality rate?

What's his actual mortality rate?

It sounds incredible, but the exact mortality rate of the coronavirus is far from known. On March 28, the World Health Organization (WHO) put the case-fatality rate at 4.6 %. This figure is calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of confirmed cases. In reality, however, we do not know. For this rate to be accurate, it would require get to know precisely the number of people infected, sick or asymptomatic carriers. Not counting those who are not reported; which is the case in many developing countries.

The only accurate data is the number of deaths. It is therefore relatively easy to compare it with that of other previous periods. Italy has just made this count and observes that the number of deaths during the epidemic period is twice as high as the number of deaths during the same period the year before.

In France, data were published on 10 April by INSEE; they establish that between 1 and 30 March 2020, 57,441 people died in France. This is more than over the same period in 2019 (52,011) but less than in 2018 (58,641), a year in which the seasonal flu had been particularly long. These figures correspond to a global view of the country's situation. If we zoom in on the regions most affected by Covid-19 such as the Grand Est or Ile-de-France, we observe a higher mortality in March 2020 compared to March 2018 - +17% and +22% respectively.

In order to have precise figures to calculate the dangerousness of the virus and to compare it with that of other diseases, it will probably be necessary to wait until the end of the epidemic.

Why can it be both harmless and very serious?

Why can it be both harmless and very serious?

The doctors taking in patients from Covid-19 are very baffled. They observe both very serious and very mild cases, with symptoms that are not much worse than those of a seasonal cold. In some cases, patients are carriers of the virus but have absolutely no symptoms. On the other hand, we have seen these terrible images of patients being carried on stretchers, put on artificial respirators and dying from a searing infectious storm.

From the beginning of the epidemic, the statistics s have shown that very serious, life-threatening cases are reserved for the elderly or those suffering from comorbidity. But as the days went by, we saw younger people dying. Or others, seemingly recovering but suddenly succumbing to a "cytokine storm", an over-inflammation caused by a runaway of the patient's immune system. Molecules involved in the control of immunity would then cause catastrophic consequences: drop in blood pressure, respiratory oedema, renal complications, which could lead to death.

Why does the virus kill young and apparently healthy people so violently and have no effect on others? We don't know. It is a mystery to doctors, but they do have a hypothesis: it is not the virus that kills, but the patient's defences that turn against it through over-activity. A hypothesis that does not yet answer the question.

What medications should be prescribed?

What medications should be prescribed?

This is the great tragedy of this epidemic. Doctors don't know what medicine to prescribe. So they just treat the symptoms - paracetamol is the standard - to soothe the patients, but they don't know how to treat Covid-19. However, the battle rages in the labs to get a drug out as quickly as possible. Several candidates are in the running, and some even, such as hydroxychloroquine, have acquired in a few days a worldwide reputation never before seen for a drug. The problem is that these drugs have never proven to be effective on this coronavirus and have no adverse effects. This requires clinical trials to be conducted according to precise and standardised protocols. This takes time and some people, such as the now famous Professor Raoult, would like to speed up the pace and prescribe his drug as soon as possible.

But health authorities, like the entire medical community, are keen to maintain a "scientific" approach. This means endless debates, forums, petitions, battles in social networks. In the meantime, doctors do not know to which saint to devote themselves and the sick are fighting to stay alive.

The issue of drugs goes beyond the medical sphere. For as long as a drug that has proven its efficacy is not available and marketed, political leaders are forced to hold containment measures or uncertain deconfinement, discordant between countries, catastrophic for overall economic activity and the mental health of all those who suffer these hesitations.

How long does immunity last?

How long does immunity last?

It's one of the other great riddles of this coronavirus. When a person has contracted the disease, even if asymptomatic, is he or she well immune and if so, for how long? The answer to this question impacts all current public health measures. Scientists have no definitive answer to this question. It is true that several studies have been conducted, including previous epidemics of SARS and MERS, which are also coronaviruses. But the results are insufficient to be applied to Covid-19 because immune responses can vary widely from one virus to another.

The Chinese led a research on monkeys carrying the virus and observed that they produced antibodies that would enable them to resist further infection. These results support the theory of acquired immunity, but they do not answer essential questions: how long does this immunity last? Does it vary from one individual to another? Can it be recontaminated?

Since the Covid-19 outbreak has occurred very recently and is still ongoing, physicians do not have enough hindsight to answer these questions. On the recontamination issue, the French government wants to reassure itself on its website claiming there are no cases of recontamination. But the Koreans have observed several cases of reactivation of the virus in people who had been detected as positive and quarantined. Some epidemiologists even believe that the virus could remain latent in certain cells and then reactivate on certain occasions such as a respiratory infection.

These are only hypotheses, and the great mystery lies in the very nature of this coronavirus. This species of organism has co-evolved with the human immune system for thousands of years, adapting to their hosts to manipulate their immune defences. Will the current coronavirus do the same? We don't know. The only way around this puzzle would be to have an effective vaccine. But it is not expected for many months.

What role does it play on children?

What role does it play on children?

If there is one certainty, it is this one: the vast majority of children are much less seriously affected by Covid-19 than other categories of the population. The figures for morbidity and even more so for lethality are very clear in this respect: most children are not ill with Covid-19. Children under the age of 15 years account for less than 1% of resuscitation admissions as of 15 April in France and no child under 15 years of age has died from Covid-19. However, this characteristic could hide a much higher infection rate. From works have suggested that children may be as contaminated as adults.

On the other hand, scientists have serious doubts about the role that children play in the spread of the epidemic. It is suspected that they are healthy carriers, that is, they carry the virus but do not develop the disease. They would then be super-propagators of the virus for some scientists, while others believe that they do not spread the disease as adults do.

Experts have no certainty about the level of spread of coronavirus by children or the infectious potential of asymptomatic individuals. Answers to this question are always accompanied by a very precautionary conditional.

Nevertheless, as a precautionary measure, nurseries and schools were closed as soon as the first containment measures were taken. They will be opened first from the first hours of deconfinement, on 11 May in France. This decision is of great concern to parents and is the subject of debate in the scientific community because nothing clearly establishes the degree of contagiousness of children or the risks they carry between children or in relation to adults.

Has he transferred yet?

Has he transferred yet?

The whole world is waiting for a vaccine by early 2021. But if the virus has mutated in the meantime, this vaccine will be useless. So the question of the coronavirus mutating is of the utmost importance. And yet, scientists do not know much about it.

Mutations are natural and random processes; coronaviruses such as seasonal influenza mutate a lot. That's why we have to get re-vaccinated every year because the virus has changed.

The precise modalities of mutation of the current coronavirus are unknown and will need to be explored on dedicated surveillance platforms such as Nextstrain. However, at this stage, it appears to geneticists that the coronavirus mutates very slowly. Its mutation rate is estimated to be 25 mutations per year, half that of the virus responsible for seasonal influenza.

Two forms of this coronavirus are already known to be circulating: the L strain, which is the most common, accounting for 70 % of cases, and the S form, which is much less aggressive. It is inevitable that the virus mutates, even slowly. What is not known is whether it will mutate to a more aggressive form or a milder form. Only time will tell.

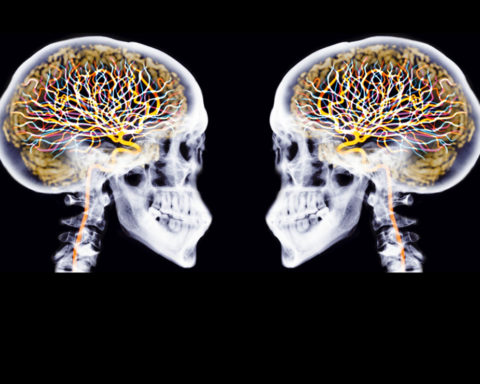

Does it also affect the brain?

Does it also affect the brain?

The coronavirus causes lung diseases, some of which are severe or even lethal. But it doesn't just affect the airways. Indeed, as early as February, Chinese scientists have been working on a study of the coronavirus. detected central nervous system disorders. The most common symptoms they observed were muscle aches, headaches, dizziness or confusion - which tend to occur with any viral infection, especially in the elderly. A few patients had more distinct neurological syndromes, including stroke, prolonged convulsions and loss of sense of smell.

But in early April, Japanese scientists publish the case of a patient on whom no trace of the virus had been found in his blood or lungs. However, by analyzing his cerebrospinal fluid, they discovered the presence of the virus. The virus would have pierced the blood-brain barrier to attack the neurons.

These cases are fortunately isolated and marginal, but the doctors are faced with the unknown. They are not able to carry out massive tests on cerebrospinal fluid and do not know how the virus got into the brain. Despite the devastating human toll of Covid-19, few autopsies are performed, leaving scientists with a major puzzle: that of a possible viral invasion of the brain.

Will the summer heat stop him?

Will the summer heat stop him?

Everybody has seen it, viruses causing respiratory diseases are seasonal. The flu is caught in winter and not in the middle of August. What appears to be obvious is tinged with nuances when we observe it outside our hexagonal perimeter. Indeed, epidemiologists point out that these respiratory viruses circulate all year round in tropical zones for example.

From then on, the mystery thickens as to what might become of our current coronavirus. There is no guarantee that it will stop at the first good days. Nor is there any evidence to the contrary.

What virologists fear is the emerging nature of this coronavirus. This one being new, the population is perfectly virgin compared to it, without any immune defence. In this case, the impact of the outside temperature is neither demonstrable nor proven.

We don't know that, and the only thing we can do is avoid catching the virus and spreading it. Only with sanitary measures could the virus be contained. Waiting until summer to see it disappear is, for now, wishful thinking.

For some time now, by dint of climatic, financial and existential crises, the dangers of the world had taught us, as if in a cure for mithridatization, that we had entered the age of uncertainty. This gradual change in the vision of the world and its risks has led each individual and each State to give priority to reaction rather than action. That is why some people are so impatient with the lack of strong action to combat global warming. It seems that we are waiting for the catastrophe to hit us hard before we finally react.

The coronavirus crisis reveals another facet of this era of uncertainty. It sheds light on the limits of our knowledge, the brutal force of nature and the long time it takes to do science. We have to admit that we do not know; whereas everything led us to believe that we were over-powerful, sitting on the throne of the gods. We are capable of going to Mars but we know almost nothing about an unfortunate virus. This pandemic reminds us of our limits and puts us in our place. We do not know. We must wait. We will. So many injunctions we can't stand, so used to having the answer to everything at the click of a button, in real time. The coronavirus reminds us there's a real world out there, too. And that uncertainty, the unknown, the unpredictable is part of it. When we know nothing, when we don't know for sure what to do, when we lack knowledge, our only point of support remains our values. We must accept this with humility and make it a strength. Our values alone will guide us into the unknown.

*This anagram is by Jacques Perry-Salkow, author notably of Four-hand anagrams, Acts Sud 2018