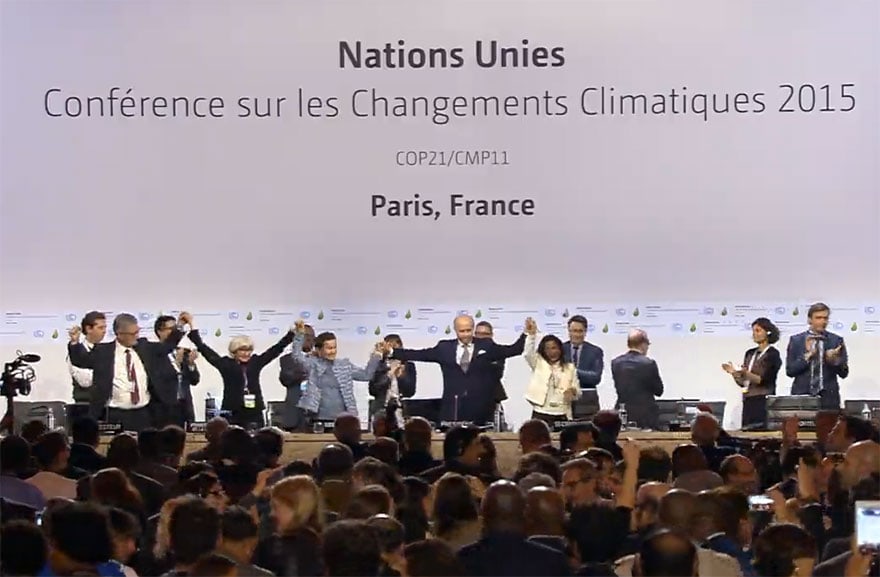

Only a few weeks before COP21, the 21ᵉ United Nations Climate Change Conference, which will bring together in Paris the representatives of all the States of the planet to sign the same "universal" contract. The objective? To find a common response to the problem of climate change, to the greenhouse gas emissions that have gradually warmed the Earth since the industrial revolution. In other words, to ensure that societies in both the northern and southern hemispheres commit, together, to a carbon emissions trajectory that will make it possible to limit global warming to +2°C by the end of the century. Without this agreement, we risk bequeathing a world at +4°C or more to future generations. COP21 is therefore the first brick in the brick of a better world, at least not a worse one.

L’The stakes are immense. Let us take the example of the ocean. It absorbs most of the heat and carbon dioxide (CO₂) that accumulates in the atmosphere; it is also the receptacle for meltwater from ice caps and continental glaciers. Without it, climate change would be even greater. But this service has a cost: the ocean is warming (+0.4°C since the last quarter of the XIXᵉ century), its acidity is increasing (+30 % over the last 250 years), and its surface level has risen (+1.7 mm/year since the beginning of the XXᵉ century, with an acceleration to +3.2 mm/year since 1993).

This disruption of the physical and chemical parameters of the world ocean has very serious implications for marine life, from calcareous organisms (pteropods, shells, etc.) to ecosystems (coral reefs, seagrass beds, etc.). Obviously, beyond the consequences for biodiversity, all this has repercussions on services that the ocean makes us more or less direct in our daily lives: fish stocks, warmer air temperatures on the coasts, favourable conditions for summer beach tourism, protection against waves, etc.

+2 °C or +4 °C, very different scenarios

Another great service provided by the ocean concerns the capture of atmospheric carbon: the more the ocean becomes saturated in CO₂, the more its capacity to regulate climate change in the future will be degraded, and therefore the faster it will accelerate. Scientists have shown that moderate to strong impacts are already being observed on marine life (on tropical corals, for example), and this trend will continue inexorably into the future. But to what extent? What future are we talking about? One in which all countries commit themselves, by signing the Paris Agreement at COP21, to sharply reduce their greenhouse gas emissions? Or a completely different future, one that is more carbon-intensive and more dangerous? This is the question that scientists, grouped together within the Oceans 2015 Initiative, have studied by comparing two scenarios of greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the century: the first characterizes rapid, substantial and sustained global mitigation efforts, and is consistent with the +2°C target; the other reflects the continuation of current trends and leads to a world that is at least 4°C warmer.

In a world at +2°C, the impacts that the ocean is already experiencing will certainly intensify, but will remain in proportions that could leave human societies some room for manoeuvre to readjust their course (for example, by restoring degraded ecosystems or protecting those gradually affected) and adapt to the changes that are now partly inevitable. In the perspective of a warming of around +4°C, future generations will be confronted with a world that will bear little resemblance to the present: a large proportion of marine organisms (tropical corals, pteropods, fish and krill) will most likely face excessively high risks of species displacement or mass mortality. As a result, economic activities and the exploitation of such natural resources will have to be fundamentally rethought, both in the North and in the South. However, the speed of environmental change in the ocean clearly raises the question of the ability of societies to find effective solutions in time. All the more so as we will also have to deal with the induced effects of rising air temperature: changes in precipitation patterns, possible intensification of extreme events of various kinds (cyclones and storms, for example), etc.

Trying to prevent irreversible impacts

This is not about "crying wolf" to make things happen "at all costs". These conclusions are scientifically robust, i.e. they are based on the most recent scientific literature, which mixes laboratory experiments, field observations and modelling, and demonstrates the consistency of these results with the data estimated during the periods of high concentration of CO₂ in the geological past. The few remaining skeptics will not mind, these findings are credible. It is therefore this overall message that must come to the climate negotiations table in the coming days: a global commitment to a rapid, substantial and sustained reduction in emissions from CO₂, which would be the mark of a successful COP21, is imperative if we are to prevent massive and irreversible impacts on marine ecosystems and the services they provide us.

The future is therefore being built today, and the ambition must be up to the task. There are two main conditions for such ambition. The first is that the climate negotiation teams in each country and the Heads of State put all their energy and power at the service of this cause. There are positive signals that are moving in that direction. The second condition is that societies adhere to the policies to combat climate change that will result from the Paris Agreement, that everyone understands why certain constraints will emerge and accepts them, on behalf of future generations. Drastically reducing our greenhouse gas emissions will indeed require profound changes in our energy and transport systems, in particular, and therefore in our individual consumption and travel patterns. In the same way, the impacts of climate change have already begun to be felt on the cycle of the seasons, the availability of natural resources (water, animals, plants, etc.), etc., and this too will affect our individual lifestyles.

Alexander K. MagnanD. in Geography, Researcher "Vulnerability and Adaptation to Climate Change", Iddri - Sciences Po

Alexandre Magnan has published various works (Ces îles qui pourraient disparaître, Des catastrophes... " naturelles " ? Climate change: all vulnerable?) as well as numerous scientific articles.

Jean-Pierre GattusoDirector of Oceanographic Research, National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS)

Photo: © Tarik Tinazay/AFP

The original text of this article was published on The Conversation.