The coronavirus pandemic still raises many questions about its origin as well as its health impacts. Its complexity comes from its entanglement in a human ecosystem in the throes of upheaval: climate disruption, pollution, chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity, which aggravate the effects of Covid-19. Moreover, the pandemic is developing on the breeding ground of our food system, whose upheavals related to globalization and industrialization of agriculture, processing and distribution are constantly producing harmful effects on human health. All these factors impact "global health" and increase the vulnerability of human organisms faced with the emergence of viral pandemics.

The current pandemic, due to the coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 with its multiple consequences, is not simple to interpret both for its origin and for its health impacts, the only ones considered here. However, it is essential to do so in order to guide and orient the choice of public policies upstream, as well as those of economic actors and citizens and consumers.

This pandemic makes the policy agenda to address the various components of the global changes that characterize the world economy even more urgent.anthropocene These include climate change, water and air pollution, which are not being addressed despite dedicated policies, as well as chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity, the current expansion of which is already a pandemic in itself. Largely dependent on our food systemThe multiple causes of these upheavals are interconnected: they relate to the globalization and industrialization of agriculture, processing and distribution, as well as the westernization of food.

Two major causes of zoonoses1 On the one hand, the risk of zoonoses is increased by the consumption and trade of wild animals, but also by land use change through deforestation and shifting agriculture. On the other hand, the human body is more vulnerable to some of these zoonoses due to a decrease in the effectiveness of our immune system. These apparently independent causes have a common feature, a decline or even collapse of biodiversityIndeed, our intestinal microbiota, when in poor condition or dysbiosis, does not protect us from infectious diseases or their complications. Finally, the decline in biodiversity in cultivated ecosystems also works in synergy with the two collapses mentioned above to accentuate their effects, or to create favorable conditions for their development. Thus, deforestation worldwide, pollution and degradation of air and land locally, intestinal dysbiosis in our bodies, all degradations that seem to have nothing to do with each other, are nevertheless a "system" and are all symptoms of dysfunction in our food system.

We will examine for each of the domains (natural ecosystems, intestinal ecosystem, cultivated ecosystems) the components of our food system that contribute to the decline in biodiversity and their consequences on the development of pandemics.

Biodiversity loss in natural ecosystems: deforestation and zoonoses

Deforestation has increased since the 1950s: five million ha were deforested per year between 2001 and 2015, mainly in Brazil and South-East Asia, at a rate that has not diminished for 50 years. The reason for this is the strong demand for soya for livestock and palm oil for industrial food and biofuels.

Oil palm plantations currently cover more than 27 million hectares of the Earth's surface. The low price of this oil on the world market and its specific properties make it mainly in demand for the manufacture of highly processed foods (frozen pizzas, biscuits, margarine...). Almost half of the palm oil imported into the EU is used as biofuel, and the rest is used for animal and human food.

Moreover, over the last 50 years, soybean production has increased tenfold, from 27 to 267 million tonnes. The increase in demand for meat consumption in the EU, and more recently in China, is at the root of this growth, since the soybean produced in the world is used to feed animals. However, this increase in Western or developed countries is not in line with real needs, since meat consumption in these countries far exceeds WHO health recommendations. This excess has led to the destruction of natural habitats through the explosion of factory farming. As the world's leading source of animal feed, soybean has thus become an indispensable element in the model of agriculture and factory farming. This development, supported by the low relative cost of animal products from this type of farming, is the direct cause of the deforestation that has led to the recent zoonoses.

Decreased biodiversity in our intestines: junk food, dysbiosis and chronic diseases, co-morbidity factors for infectious diseases.

Over the last 50 years, deaths related to infectious diseases have decreased thanks to health advances and the use of antibiotics. On the other hand, chronic non-communicable diseases have increased sharply, in particular due to "junk food", the consequence of which is overweight and obesity, which are the gateway to diabetes with its associated pathologies. The Covid-19 pandemic reveals that these are also risk factors for the development of serious forms of the disease, since it has been observed that the number of patients in intensive care, as well as the percentage of those who die, almost all have one or more chronic diseases (obesity, diabetes, etc.). This observation made in countries as different as China, Italy, France and the USA means that the prevention of chronic diseases should also play a key role in the prevention of infectious diseases or the lethality of their complications.

Our microbiota is a key factor in health and disease. Indeed, humans and microbes have established a symbiotic association over time, and disruptions in this association are the cause of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. These chronic, highly disabling diseases affect different organ systems. Disruptions in the microbiota are risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases, obesity, diabetes, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, but also brain diseases; a considerable part of their pathology is due to our diet and our environment. The processes involved are inflammation, oxidative stress caused by a lack of certain nutrients (fibre, omega 3), excess of others (omega 6, highly processed products, rich in fats, sugars and containing additives) as well as contaminants (pesticides, endocrine disruptors). Some data

Furthermore, it is known that the innate immune response to viruses inhibits their replication, promotes their elimination, induces tissue repair, and triggers a prolonged adaptive immune response. Thus, in most cases, the pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses associated with Covid-19 are triggered for our benefit by the innate immune system when it recognizes viruses and attempts to circumvent them. But several factors can make this response excessive, inappropriate and even fatal. In addition to aging, which impacts the diversity of the microbiota, the lower effectiveness of our immune system depends on the co-morbidity factors of chronic diseases. The development of antibiotic resistance acquired via the air, water, etc. aggravates the situation, and it is now recognized as a major problem for bacterial infections: independently of Covid-19, pulmonary infections resistant to antibodies to prevent the spread of viruses, such as bacteria, viruses, bacteria, and viruses of other pathogens, are more likely to occur.

Loss of biodiversity in soils and landscapes: industrial farming systems, pollution and reduction of food supply in the territories

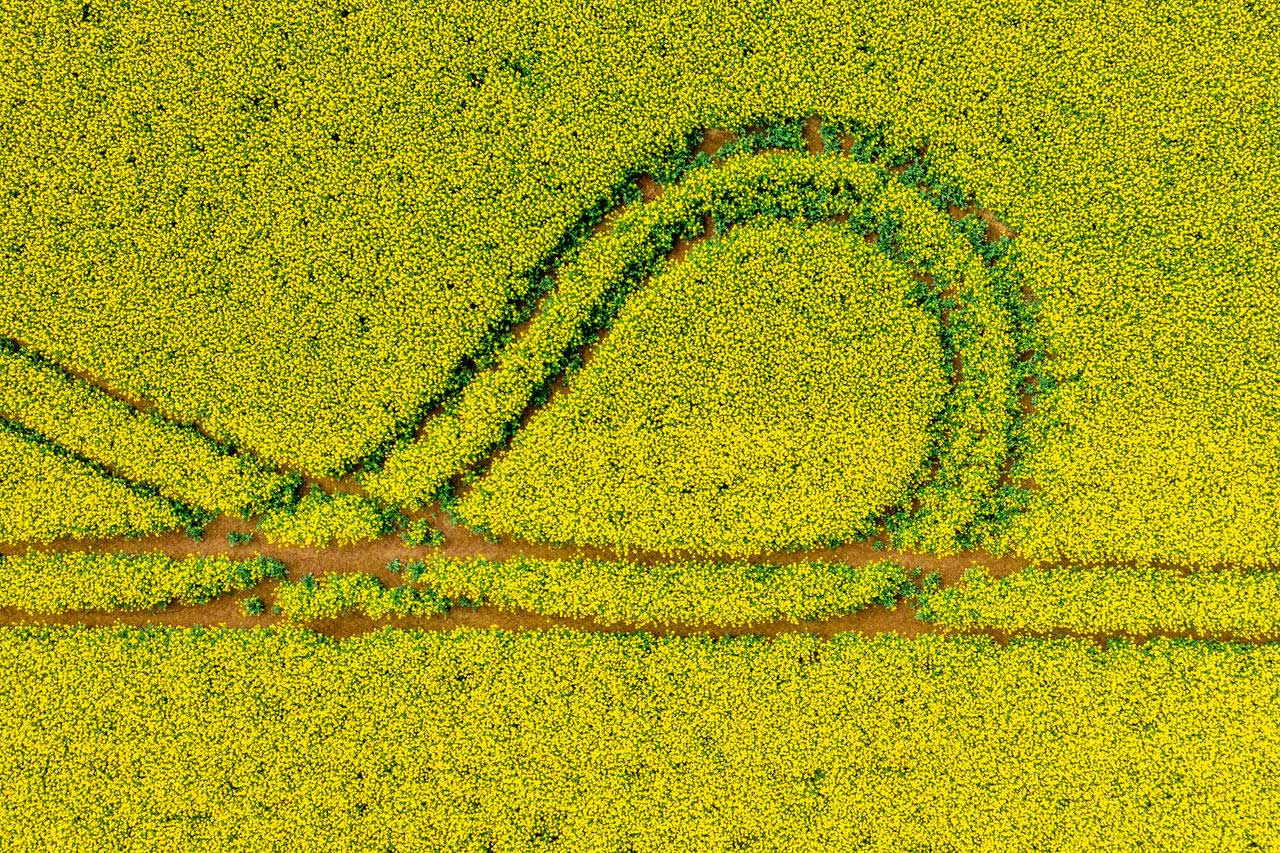

Biodiversity dynamics observed in natural ecosystems and in our gut are also concomitant with declining biodiversity in agricultural soils and landscapes. Simplification of cropping systems such as farm and regional specialization is leading to increased use of synthetic inputs (nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides) in an ever less effective attempt to compensate for the loss of services provided by "nature". For example, very few legumes are grown to fix nitrogen from the air, due to farm specialization in wheat, rapeseed, maize and sunflower. And we import a large proportion of seed legumes for our food while we do not consume enough of them for our health.

We also import a lot of vegetables, sometimes from far away, often with a high environmental impact, when our consumption is already very insufficient for our health, our climate is perfectly adapted to these crops, and they are excellent providers of antioxidants and vitamins.

In addition, in some regions, the high concentration of intensive livestock production dependent on soybeans or inputs exogenous to the region is also associated with high nitrate water and ammonia air emissions, as well as overuse of antibiotics which, together with antibiotics used in human medicine, contributes to the development of antibiotic resistance, the harms of which have been seen.

Global health for understanding and action

Since biodiversity is threatened or has reached critical thresholds in many areas that are very different from one another, it must be restored in a coordinated manner and for preventive purposes in order to ensure the conditions for what will be called "single" or "global" health. Consequently, sectoral policies by field, agriculture, environment, food, health, international trade, which only aim to reduce impacts without touching the system are no longer sufficient. The current vision of the world as unlimited in resources, the compartmentalization of "silo" policies, which address problems in isolation, as well as the mirific belief in the capacity of new technologies alone to save the world, are therefore insufficient and inadequate.

The development of systemic policies is the only urgent response to this systemic crisis. It is the necessary condition to reduce not only the impact and risks of future pandemics but also to face the catastrophic consequences of our food system on health and the environment. Its contribution to climate change amounts to about 25 % of greenhouse gas emissions via nitrogen fertilizers, methane (ruminants, rice fields) and deforestation. How can we reduce 50% emissions in order to reach carbon neutrality in 2050?

Taking environmental and health issues (chronic diseases, but also zoonoses) really seriously requires rebuilding relationships between the different actors in order to think about and implement a transition of the food system as a whole. It is important to take into account difficulties and/or failures such as the management of trans-scale dynamics, persistent inequalities in food rights, power imbalances and contradictory values and interpretations of food security.

Writing a new narrative about the health of organisms and populations (humans, animals) and their habitats (soil, ecosystems, etc.) is a way to rethink public action and give perspectives to collective action.

In the field, a multitude of initiatives (Amap, territorial food plans, short circuits, responsible collective catering, farmers' markets, etc.) are moving towards an agro-ecological transition of food systems. However, the effects on the French scale are difficult to see because these initiatives sometimes ignore or compete with each other, have difficulty capitalizing on skills, and often involve only part of the changes to be made: they concern agriculture or food, but rarely both. The coordination already underway must therefore be strengthened in order to change the scale and make these initiatives visible to as many stakeholders as possible. To this end, the food system scenarios developed by the researchers provide convincing reference points for developing territorialized food systems and giving credibility to the choices made. However, beyond these initiatives, it is important that the

Michel DuruDirector of Research in Agronomy at INRAE. His work initially focused on agriculture (crops, livestock) and the environment. He is currently working on the "agro-ecological transition of food systems". The challenge is to define systemic innovations for healthy and sustainable food, taking into account the finiteness of resources (land, phosphorus, etc.), while reducing our impacts to cope with climate change and pandemics such as obesity and certain infectious diseases.

1] Disease of bacterial, viral or fungal origin transmissible from animals to humans.