This report was supported by the Pulitzer Center. It originally appeared in Rolling Stone. It is republished here as part of UP' Magazine's partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 selected media outlets to strengthen journalistic coverage of climate change.

This report was supported by the Pulitzer Center. It originally appeared in Rolling Stone. It is republished here as part of UP' Magazine's partnership with Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 selected media outlets to strengthen journalistic coverage of climate change.

It is June, the beginning of the fire season in the Amazon. Fires are starting to rage all over the forest, the final stage of clearing land for grazing. The smoke is getting so thick that it is visible from space and difficult to breathe here on the ground. But from where I'm sitting, in a dented van heading south, I can barely see through a dust storm.

I'm on BR-163, a congested road from hell that has been under construction since Brazil was ruled by a military dictatorship forty years ago. I am in the heart of the state of Pará, in the north of the country, 2 000 kilometres from the Atlantic coast and three days' drive from Rio de Janeiro. For the past two hours we have been sailing through potholes the size of a lunar crater and driving around a caravan of semi-trailers. Snaking south through the Xingu Basin, the BR-163 starts in Santarém, a wet port city on a tributary of the Amazon, and ends 1,500 kilometres further south, in the breadbasket of Brazil, the state of Mato Grosso, a name that can literally be translated as "thick jungle. Now almost completely barren, much of the landscape resembles Kansas.

The road we are on leads us to Brazil's future as a commodity superpower. No country exports more soy and beef than Brazil. We pass hundreds of trucks heading for the Amazon ports, loaded with soybeans, where they will be unloaded onto cargo ships bound for Europe and China. At ten degrees from the equator, BR-163 is a kind of dividing line, a boundary point between the natural world and what seems to be its destiny: an industrialized monoculture that moves north every year.

This explains why BR-163 has become so well known - few areas of the Brazilian Amazon have experienced more rapid deforestation in the last decade. I've been told that if I want to understand the forces behind the destruction of the most important brake on climate change, this is where we need to go.

Why not enjoy unlimited reading of UP'? Subscribe from €1.90 per week.

Within a few weeks, fires will be lit all along this road, intentionally set by the farmers who live here. In August, nearly 80,000 fires will rage in the southern Amazon, projecting a river of smoke that will darken the skies over São Paulo and cause an international outcry, focusing the world's attention, however briefly, on the ground where I am now.

As we pass a crumpled landscape of razed jungle, my guide, Gabriel, explains to me the pattern of destruction. Precious woods are first extracted, followed by mining, then cattle breeding, which is the main driver of deforestation. The final stage is the planting of soya, from which there is no return. Already, huge swathes of what was once a rainforest biome have been transformed into savannah, and unless something radically changes, this seems to be the future for what remains of the forest along BR-163.

What's happening in the Amazon affects us all...

One way or another, everything that grows here ends up in the global supply chain. Forty per cent of Brazilian beef is raised in the Amazon, and most of it is processed by the world's largest beef supplier, the Brazilian company JBS. Brazilian beef is shipped around the world, mainly to China, Hong Kong and Europe, but much of the meat is also exported to the United States - 31,000 tonnes last year, mostly in the form of corned beef and pet food. Leather from cattle raised in the Amazon is used, according to Trase, a Stockholm-based NGO that tracks supply chains, by major furniture and car manufacturers in the United States. And most of the semi-trailers we see on the BR-163 are headed to a large plant in Santarém owned by Cargill, the largest privately owned company in the United States, where the soybeans will be processed into animal feed for cows and chickens, which will then be consumed in fast-food chains around the world. In other words, what is happening in the Amazon affects us all.

I'm heading to the front line of a battle for the future of the forest. It is a lawless zone where cattle ranchers, gold miners and logging companies are moving closer and closer to one of the largest intact indigenous reserves in the southern Amazon - an area of 55,000 square kilometres that includes the villages of Baú and Mekragnotire, home to the Kayapo people. I want to see if the forest can be saved before industry kills it for good.

From Indonesia to the Congo, the world's forests, a fragile buffer against climate change, are disappearing. In 2017 alone, 160,000 km2 of tropical forests have disappeared. That's the equivalent of 40 football fields disappearing every minute for an entire year.

Nowhere is the stakes higher than in the Amazon, which has 40 percent of the world's tropical rainforests and more biodiversity than anywhere else on the planet. Two of the world's leading climatologists, Carlos Nobre of Brazil and Thomas Lovejoy of George Mason University, estimate that if an additional 3 to 8 % of the forest were to disappear, it would begin to burn itself out. In February 2018, Nobre and Lovejoy published an post announcing that we're on the brink. In 2016, for the first time in history, the Amazon released more carbon into the atmosphere than it absorbed. The causes - widespread drought and forest fires - were in themselves the effects of climate change, but Nobre and Lovejoy warn that if deforestation in the Amazon continues at the current rate, more than half of the rainforest could die permanently, a devastating climate change scenario with terrifying implications. Weather conditions would change throughout South America and billions of tons of carbon would be released into the atmosphere.

Brazilian tragedy

The tragedy of what is happening in Brazil, home to 60 percent of the Amazon rainforest, is that, under the aegis of the leftist Labour Party, deforestation fell by 70 percent between 2005 and 2013 as a result of a series of aggressive reforms, including the setting aside of 150 million hectares of tropical forest, a protected area roughly the size of France. Space agency surveillance satellites have triggered real-time alerts of forest loss, farmers caught cutting down trees have lost access to credit, and an elite team of environmental cops has targeted the worst culprits, flying to areas of destruction by helicopter, where they have destroyed machinery used for mining or burned tractors and bulldozers used to destroy the jungle. What they did not destroy, they confiscated.

In 2014, the trend has been reversed. This coincided with the worst corruption scandal in Brazilian history, which ousted the Workers' Party and gave rise to a far-right political coalition. Under the presidency of Michel Temer, a long-time boss of cattle and soybean farmers, the budget of the Ministry of the Environment was cut and the agency charged with protecting Brazil's indigenous reserves, FUNAI, had to fight attempts by the agricultural lobby to destroy it. Despite this, dozens of FUNAI bases were closed and their budgets cut by almost half.

Then came Jair Bolsonaro. Former captain of the army of Rio de Janeiro, a fetish of the Brazilian years under military rule, he is known as the trump card of the tropics. Racist and homophobic, no one took him seriously when he ran for president; he had once told a colleague in Congress that he would not rape her because "she was not worthy" - she was "too ugly".

But by aligning the growing evangelical voting bloc in Brazil with the agricultural lobby, also known as the ruralists, Bolsonaro drew its momentum from the global populist wave. Like Trump, he expressed an open contempt for science, and declared climate change to be a Marxist conspiracy. He promised to open up the Amazon to development and pledged to eliminate environmental impact assessments for infrastructure projects bogged down in bureaucracy. Roads that had not been paved for a long time, such as BR-163, would be completed. And it would not allow "an inch more of indigenous land.

To fight against disinformation and to favour analyses that decipher the news, join the circle of UP' subscribers.

Since Bolsonaro took office in January, the trees in the Brazilian Amazon have been disappearing at a rate of two Manhattan per week. This summer, INPE, Brazil's space research agency, announced that satellite imagery showed that deforestation had increased by 278 % in July compared to the previous year. In response, Bolsonaro questioned the data, fired the director of INPE and threatened to close down the entire agency.

"What is happening is unprecedented," says Jose Sarney Filho, who served as Minister of the Environment under two presidents. "This new government is trying to destroy what we have built in 30 years. »

Under Bolsonaro's leadership, cattle barons and farmers in the Amazon are acting with impunity. "What is really heartbreaking and discouraging is that for more than 10 years we have shown the world that deforestation can be stopped," says Marina Silva, a former environment minister and presidential candidate. "I don't think people realize how fragile the forest is, and how quickly it could disappear. »

The king of deforestation

We've been on BR-163 for six hours. Gabriel's driving carefully to avoid rocks and unexpected ruts in the road. Lilo, who is accompanying me, is an experienced photojournalist from São Paulo. He shows me potholes, stops to take pictures of strange animals killed on the road and helps me to recognize the difference between vultures and other large birds circling over the jungle. "We're lucky it's not the rainy season," says Gabriel. The road would be impassable. Sometimes soybean trucks get stuck here for weeks. Last winter, the military had to airlift food and supplies, and some truckers simply abandoned their loads.

We head to Novo Progresso, a remote and isolated outpost in the jungle about 10 hours from the port. BR-163 is the only way in and out. Cut in two by the highway, the town of about 25,000 inhabitants is surrounded by tropical rainforest and has a Wild West atmosphere. The streets are mostly unpaved and dusty and lined with shops that supply gold miners, ranchers and loggers.

This is the house of the so-called king of deforestationIn a recent case, a man whom federal investigators compared to a mafia boss allegedly under investigation for keeping workers in slave-like working conditions and for cutting down large tracts of national forest to make way for cattle ranching and land speculation. He owns a car dealership, a chain of grocery stores and is linked to the political elite that runs the city. IBAMA, the agency responsible for protecting the forest, operates from a base on the outskirts of the city, but does not allow its agents to leave its walled enclosure. They have seen their trucks burned and faced so many death threats that they only operate under the protection of the Brazilian Federal Police. Informants working at the request of the land grabbers follow the movements of the agents. We are heading towards a war zone.

As we approach the town, Lilo and Gabriel exchange stories about what they have heard about other journalists who have come to Novo Progresso. A colleague was invited to leave shortly after her arrival at the hotel," explains Lilo. When she ignored the warning, she found an envelope under her door. It contained three bullets. Gabriel has a friend who came here with an NGO a few years ago. Armed men surrounded the hotel and ordered them to come out so that they could "shoot the environmentalists". A police escort had to take them out of the city.

That evening, in a pizzeria on the main street, it is immediately obvious that most of the city's inhabitants are immigrants from other parts of Brazil, mainly from the south. They have German names and European traits; Lilo and Gabriel quickly recognize accents of states such as Paraná and Rio Grande do Sul. They are the children of immigrants who arrived here a generation ago under one of the largest resettlement programs in the country's history, where the generals who ruled the country lived in the paranoia that if they did not occupy the Amazon, a foreign power would invade.

Thus, in an ambitious plan, the Brazilian government offered large plots of land to anyone who would agree to fly and be dropped off in the forest. As in the Oklahoma land rush of 1889, the government did not care that the forest was, in fact, already occupied. The results were disastrous. Dozens of tribes disappeared and, with no forest management program in place, the settlers cut down and burned the jungle. When BR-163 passed through Kreen-Akrore territory, 250 tribal members died of disease within 12 months of contact with road workers.

"There were only trees and forests, and it was mostly people from other parts of Brazil who had no idea how to live in the Amazon," says Sister Jane Dwyer, a religious I met on the Trans-Amazon Highway. She has been living in the Amazon since 1972. "It was nine to ten months of rain. Snakes. Malaria. I don't know how people survived. They didn't, most of the time. »

The development of Novo Progresso occurred along the way, a model followed throughout the Amazon. Livestock was the cheapest way to occupy and claim the land. Unlike soybean plantations in the south, which required expensive fertilizers, processing machinery and infrastructure for irrigation, livestock needed only raw fencing and seed for grazing.

The man who was to become the king of deforestation, Ezequiel Castanha, moved to Mato Grosso in the 1980s as a teenager, and by the age of 25 he had opened a mini-market that served a gold mine on the border of Mato Grosso and Pará. By the early 2000s, so many forests had been cleared in Mato Grosso that land was becoming increasingly expensive. Castanha heard that he had to follow BR-163 northwards to what was rapidly becoming Brazil's new agricultural frontier.

He arrived in Novo Progresso in 2003, and already tensions about the future of the forest were rising. That year, when federal agents came to mark the boundaries of the new reserves of Baú and Mekragnotire, a crowd of hundreds of herders, loggers and miners, often armed, led about 1,000 citizens to close the road in protest. Then they entered the forest, vowing to hunt down the agents.

"I got tired of trying to keep them on the highway," Agamenon Menezes later told the press. Menezes is the president of a livestock union called the Rural Producers of Novo Progresso, and the town's de facto boss. He said the situation could have escalated and that his men were shooting to kill. "When a hunter enters the woods behind his prey, the rifle is ready to shoot. »

President Luiz Inacio da Silva and his Labour Party coalition made Novo Progresso and BR-163 the focus of their ambitious plan to slow deforestation. The administration, da Silva announced, will complete the paving of the road, but only if it can preserve the forest at the same time. In 2006, it created the Jamanxin National Forest, just north of Novo Progresso.

The forest was now out of bounds for development, but it already contained more than 250 illegal farms, including one owned by the mayor. There was no way to legally own property there, even before it was declared a national forest.

"In the rest of Brazil, a title deed proves who owns the land," Daniel Azeredo Avelino, former federal prosecutor of the state of Pará, told Brio, a Brazilian online magazine. "The number of people with a title is very low. From 80 to 90 % of the properties in the region do not have this document. »

In 2006, IBAMA officials examined satellite images from their office in Brasilia, the capital of Brazil. The imagery of the area around Novo Progresso was shocking. A piece of forest had simply disappeared in a few days. They flew there to see for themselves and found a 400-hectare clearing between the road and the Curuá River, which meanders through the Bau Reserve. There were already six farms in the area. The land had been cleared by Castanha.

As IBAMA increased its operations around Novo Progresso, threats against the agents intensified and in April 2011, a crowd invaded the IBAMA complex on the outskirts of the city. Through informants, they knew of agents who were planning to raid a farm in the Jamanxin Forest belonging to the deputy mayor. A helicopter was about to take off and the crowd attached steel cables to the propellers to prevent the operation from moving forward.

A few days later, the director of the local IBAMA agency called a meeting with the mayor, the city council and city officials to calm things down. This time IBAMA agents came armed. In the middle of the meeting, Castanha stood up. He admitted that he had cleared a piece of land in the national park and sold it to a local doctor, who eventually became deputy mayor.

Castanha didn't apologize. "If we don't clear the forest, our land becomes a reserve," he told the head of IBAMA. "It was you who made us clear the forest. »

IBAMA officers and the federal police began to further investigate Castanha's business activities, studying his taxes and financial transactions and tapping his phone. They alleged that he was sitting at the top of a sprawling criminal organization that stretched from the Amazon to São Paulo and southern Brazil.

By 2014, Castanha had accumulated $9 million in fines, had been indicted 16 times for environmental crimes and had had nearly 5,000 hectares of land confiscated for illegal land clearance. In 2015, federal officials estimated that he alone was responsible for 10 % of deforestation throughout the Amazon.

He refused to pay the fines and continued to treat the land as his own. A wiretap showed that, through a real estate agent, he had broken up land that he had illegally seized into lots for sale. When a journalist from the national news programme Globo Rural interviewed him that spring, Castanha said: "If we didn't deforest, there would be no Brazil. There would be nothing. »

On 27 August 2014, just before dawn, 96 federal agents descended on Novo Progresso, wearing bulletproof vests and assault rifles. Dressed in black, they rushed to IBAMA headquarters and, after calling for reinforcements, broke into small platoons and dispersed throughout the town. They arrested members of Castanha's gang, including the leader of his land-clearing team and a lawyer who had spent the last few days shredding incriminating documents, but Castanha was on the run. He remained at large for almost six months. In February 2015, working on a tip from an informant that Castanha was back in Novo Progresso, federal agents returned, and this time Castanha surrendered.

Video footage of Castanha, handcuffed to a waiting helicopter, was broadcast that night on the national news. The king of deforestation had been caught. Officials estimated that his gang was responsible for 20 % of deforestation in the Amazon in recent years and accused him of environmental crimes and money laundering. But within a few months he would be released from prison (his case has not yet been tried), and soon deforestation along the BR-163, which had dropped by 65 % in the seven months following the issuance of an arrest warrant against Castanha, would begin to increase.

The Kayopo War

The Kabu Institute is right next to BR-163, behind a concrete wall. Officially the headquarters of a non-profit association that supports the Kayopo, it is also a gathering place for the tribe members who enter and leave the Novo Progresso.

On the morning of our visit, the sun rises just above the jungle. Several Kayopos are sitting on the porch, smoking cigarettes and waiting for the opening of the institute. The smell of freshly cut wood floats in the air.

Today, the Kayopos are one of the richest and most powerful of Brazil's 240 tribes, but in the late 1970s, when the Trans-Amazon Highway was completed, their population grew from 4,000 to about 1,300. Over the following decades, a series of legendary chiefs found a way to adapt their warrior culture to the modern world. They patrolled their borders and commandeered strategic river crossings. They partnered with non-profit organizations and joined with celebrities like singer Sting to protest the construction of a dam that would flood their lands. They also used force: they attacked ranches and gold mines that were illegally occupying their land, taking hostages or warning intruders that they had two hours to leave or they would be killed. Some were killed. Others were sent back to town naked and humiliated.

A few years ago, the Kayopos participated in an operation against a man named AJ Vilela, who succeeded Castanha as the new king of deforestation. Based in Castelo Dos Sonhos, a town a few hours south of Novo Progresso, the project had similar contours: land speculators who illegally seized the forest worked with real estate agents to offer properties to investors in the South. But unlike Castanha, Vilela didn't even live in the area - he ran the operation from one of São Paulo's richest neighbourhoods, Jardim Europa.

The son of a cattle baron accused in the 1980s of trying to poison Indians with arsenic, Vilela was a pillar of jet set society (he married a famous Brazilian jewelry designer in St. Barths; his sister appeared in the Brazilian edition of Vogue) and had family ties to some of the biggest players in Brazilian agriculture.

Vilela operated for years before IBAMA even detected a forest loss because her teams left the canopy intact, sparing the taller trees and obscuring the cleared fields from satellite imagery. Then, in April 2014, members of the Kayopo arrived in the capital covered in war paint, carrying bows and arrows. They waited for the head of IBAMA to leave his office and cornered him in the parking lot. The land inside their reserve was disappearing and they needed IBAMA's help.

Together, they launched Operation Kayopo. IBAMA agents studied telegraphic transfers and land titles, and the Kayapos travelled through the forest looking for deforestation camps. Eventually, they captured 40 people who were clearing the forest and, together with IBAMA agents, interviewed them to understand the operation.

At the time of Vilela's arrest, her gang had already cleared 5,000 hectares, an area five times the size of Manhattan. IBAMA leader Luciano Evaristo said the operation was a rare success and that cooperation with the tribes was the only way to stop deforestation. They were the real intelligence force in the jungle, able to spot what satellites could only detect after the fact. But all this happened under the previous presidential administrations, before IBAMA was paralysed and its activities simply stopped.

Inside the Kabu Institute, a staff member shows me how pastoralists are encroaching more and more on the villages of Baú and Mekragnotire. He shows a map on a computer screen, with green dots marking the forest and red dots indicating cleared land. The buffer zone between BR-163 and the reserve was about 110 km long, he says. Now there is almost no buffer zone. Herders are clearing the forest at the boundary of the indigenous reserve, and he fears that one day they will invade the reserve itself.

Local hero

Nobody wants to talk to us about Castanha, it seems. North of the city, we heard that there is a squatter settlement and that an activist who lives there wants to talk to us, but she sends us a text message saying that it is too dangerous and that she is afraid to come to the city. We offer her a ride to the camp, but she stops communicating.

A farmer who promised to talk unofficially about the Novo Progresso criminal network tells us he will meet us for dinner one night and never show up.

I will need a presentation from Castanha, suggests Lilo, and I will start with Agamenon Menezes, the president of the rural producers of Novo Progresso, the local association of cattle breeders. There is a similar group in almost every city in the Amazon, and they all wield significant political power. Menezes is said to have his own militia.

We found him in a crappy office downtown. The walls are dirty and the place smells like musty jungle. There are posters on the walls of cattle and tractors. There's a bushel of soybeans in a file cabinet. Menezes is sitting behind a big desk. He's a slim, dark eyed, short-haired man. He speaks in a low mumble and spices up his sentences with a smile that seems threatening. His hands shake as if he has early Parkinson's disease.

He explains that like most of the city's "pioneers", he arrived in the 1980s, when there was only dense forest here. He says he contracted malaria more than 70 times and remembers when the road was so bad that he got stuck and had to walk home for 17 days. When he speaks, it is clear that he is proud of what Novo Progresso has become. He does not see himself as someone who has launched an unprecedented destruction of the forest. He sees himself as someone who brought civilization to a frontier that his government wanted to colonize.

We came here because this same government, which now calls us bandits and criminals, sent us here," he says. "We were scouts, and now they're putting us on the news as bad guys. »

He tells me that Castanha is a local hero who stood up to a tyrannical government that would fly to cleared land and destroy tractors and burn fences without due process.

"He came at an opportune time and did what many people wanted to do but were afraid to do," says Menezes. "He opened farms and sold farms. He's a leader here, highly respected. »

Things are different under Bolsonaro," says Menezes. The president understands that the rural producer is the engine that drives Brazil. He was arrested at IBAMA, an agency that Menezes says exaggerates reports on deforestation, or simply makes them up. "They came here violently burning equipment and so on, always with the media in their helicopters," he says. "Now, thanks to Bolsonaro, they've been taught good manners. They came here and talked to me the other day, respectfully, and told me that they were taught how the government should act. »

Menezes lists some of the actions he has ordered over the years, such as sending his men to an airstrip where a documentary film crew was ready to leave for home. They were flying around, filming farms cleared in the forest. Menezes told me his men destroyed the crew's cameras and their footage.

He also tells me that he is the reason why NGOs active in the preservation of other parts of the Amazon have not been able to establish themselves here.

"NGOs, and you media, come here and paint us as bad guys. That's why I won't allow any of them to come here." he says about NGOs. "I will do everything in my power to prevent them from settling here. »

"Like what?" I'm asking.

"Like burning their cars," he says.

An awkward and tense silence fills the room.

He bends his gnarled hands over the belly, the belly of an old man, and bends over his chair.

"We will preserve our way of life. »

"The air's different here, isn't it? »

One morning, we get up before dawn and head east towards the Baú and Mekragnotire reserves. We travel with Kudjekre Kayapo, a member of the Kayopo tribe who works at the Kabu Institute. As we walk along a small dirt road, the forest closes around us and a mist rises from the canopy. I roll down the window and suck in the air, which is humid, rich and fresh. Kudjekre looks at me and smiles. " The air is different here, isn't it? »

We drive about three hours before arriving at a small river that marks the limit of the reserve. Kudjekre makes a call on his cell phone and a few minutes later we hear the rumbling of a small fishing boat and a member of the tribe takes us across the river.

In Brazil, indigenous communities are called aldeias. Typically, they are small clearings in the forest where a dozen thatched huts spread out in a semicircle. When we arrive, most of the tribe members, who had heard we were coming, are gathered under a kind of pavilion called the warrior council. All the men are painted black. The women have black tattoos that fade after a few weeks.

Although the Kayopos have retained their traditional customs and, for the most part, live like their ancestors, it is clear that the modern world has infiltrated them. A group of young men carve sticks, checking out Facebook from time to time on their smartphones. A man leaning on a motorcycle smoking a cigarette points to the front of the lodge, where the chief sits on a bench roughly carved out of a large log.

His name is Cacique Ireo Kayapo, and he asks me to sit next to him. He has painted a thick strip of black paint over his eyes and along his belly, which is beaded with little drops of sweat. Another man from the tribe is sitting next to us, translating.

Ireo speaks nostalgically of the years before the tribe saw miners or lumberjacks. In the 1980s, the reserve land wasn't even marked, and the only white men they had seen were from the FUNAI.

The miners arrived around 2009," says Ireo, "and at first the tribe thought that working with them might be a good thing. But soon after, the money they brought had pitted neighboring tribes against each other, and the alcohol brought by the miners had ruined the men and families. After the miners, then the loggers, then the lumberjacks, with their fire and their shots and their smell of smoke and destruction.

We don't want to get mixed up with these people anymore," says Ireo. "We don't want white men on our land. »

He is concerned that the Novo Progressso breeders have their eyes fixed on the reserve. In a compromise, the Kayopos had already agreed to reduce the size of the reserve, hoping that this would put an end to encroachment into the forest. But nothing has changed. They are getting closer every year and swallowing more and more land.

A week before my arrival at Novo Progresso, I was at a ranch outside Redenção, where I met Jordan Timo. Tall and thin, dressed in cowboy boots and a white straw hat, Timo told me that he had formed his first cattle herd just outside the Kayopo Reserve, near the city of São Félix do Xingu, which has become synonymous in Brazil with explosive deforestation (in 1980 the city had 22,500 head; his herd is now the largest in Brazil: 2.8 million, a staggering figure).

When Timo arrived in São Felix, he was surrounded only by forest. When he went to town, he traded a cow for gold to hungry miners, then slept through the night with a Winchester gun in his lap to avoid being robbed by drunks leaving bars and brothels.

The only way: deforestation

"It was very violent," Timo told me. "The big problem on the border is that there is no state, no electricity, no water, no school. »

And no one to know how many forests he or anyone else was clearing. So he rounded up men from brothels and street corners in São Felix and promised to pay their bills. He then took them to a discount. Once he had huddled there, armed men led them to a ferry that took them up a river to his ranch, where they were forced to stay until they had cleared the forest.

"Was it forced labour? Maybe it was," Timo admits. "But there wasn't really an alternative, it was the reality of the world. »

Timo tells me that he regrets having cleared so many forests and that he resorted to slavery to do so. "When I first came here, the only way out was through deforestation. Even if I wanted to legalize one of my employees, I would have had to travel 1,000 kilometres to sign a work card, so I used methods that everyone else used. But there comes a time in your life when you think between right and wrong, between the law and the lawless. »

Today, he fights deforestation by running a software company that tracks supply chains. The software is used by slaughterhouses who want to make sure that the cattle they buy have not been raised on illegally cleared land, on indigenous territories, in conservation units or on ranches that use forced labour. In 2016, 46 per cent of the meat sold in Pará passed through its computerized tracking system.

This number should be higher. Under the law, slaughterhouses operating in the State of Pará, which has more than 250 000 farms, are required to follow their supply chains, but only 63 slaughterhouses have complied with the law, while 65 refuse. As a result, approximately 18,000 cattle a day are slaughtered in the Amazon without any environmental monitoring.

"Some people try to follow the rules and others don't really try," says Timo. "It's cheaper and easier to clear the forest than to follow the law, and there's no real punishment for those who don't do it. »

Even those who monitor their supply chain, such as JBS, the world's largest beef producer, have no way of knowing where all the cattle they slaughter come from. Illegal ranchers can raise calves up to a certain weight and then sell them to a licensed rancher, who then sells them to major slaughterhouses. (In a statement, JBS said, "We have a zero deforestation policy in the Amazon and we prohibit cattle from deforested farms in the region from entering our supply chain," adding that they monitor more than 50,000 suppliers and have blocked more than 7,000 for non-compliance).

Timo says this problem of "cattle leakage", or illegal cattle laundering through clean pastures, would be easy to solve. It would simply involve putting an ear tag with a microchip on every cow born in the Amazon, a system that has been used for years in the United States and Canada. He says it would cost less than 5 $ per cow.

"We don't need to create any more monitoring tools," says Timo. "The tools are there. The laws are there. What we lack are police resources to crack down on it. »

Timo says that most cattle breeders in Pará are trying to comply with the law. The problem is that poor farmers often can't afford it. Because the Amazon is so vast, trucking fertilizer to keep pasture green for months after the rainy season is prohibitively expensive. It is much easier to simply clear the forest and then move livestock to another pasture once the forest is degraded. Most Amazonian pastures are abandoned within 10 to 15 years.

"We have a lot of sticks and not enough carrots," says Marcelo Stabile, an agronomist at IPAM, the Amazon Environment Research Institute. "We need to invest more in the rural producer to help him make better use of his land. »

Timo agrees, but says that the only thing that will really put pressure on the Brazilian government to enforce the law is market forces.

"If there is no commitment from consumers, not just in Brazil but around the world, to look for ethically sourced beef, then farmers here will continue to look for the easy way out, and that is deforestation.

Just the mention of his name makes people nervous.

The last morning in Novo Progresso, I decide to pass in front of the supermarket in Castanha to see if we could find it. It's our last chance. So far, no one has agreed to organize a meeting; just mentioning his name makes people nervous. His shop, called Castanha Supermercado, occupies a whole block. He has a couple of them scattered around Novo Progresso, but I think the one right next to BR-163 is our best chance to find it.

It's a Catholic holiday today and the supermarket is one of the few places in the city that is still open. Most of the city's businessmen have gone to their ranches to barbecue and drink beer. Gabriel, my companion, says it is unlikely that Castanha is there.

We go into the market and ask for Castanha. The woman sitting at her desk looks at me and raises her eyebrows. She glances over her shoulder at a large corner desk behind a glass so darkly tinted that I can't see if anyone is hiding behind it. She scribbles my name and passes the word to another worker, who disappears into the office.

I'm sitting in the middle of a row of chairs in front of the supermarket when Castanha suddenly appears. He is a tall man, much taller than I expected, at least six feet tall, with fleshy hands and broad shoulders. He's wearing cowboy boots and jeans. A big smile spreads across his face as he shakes my hand and welcomes me into his store.

"I can't talk to you," he says. "My case is still in court and my lawyer says it's best not to talk to the press. »

But he talks so fast I fumble to get my tape recorder out of my pocket. He admits that he cleared the forest, but wonders if it was really illegal. He loves the forest. He shows his shop signage, which includes a collage of images of rivers, crocodiles and leopards. His name, after all, is Castanha, which is the Portuguese word for Brazil nut and the tallest tree in the forest.

People in this town just want to make a living, he says. He talks about a story I have heard over and over again, that the government sent people like him here to settle the land. Now they are suddenly changing the laws, declaring farms off limits, imposing fines, destroying equipment. Only because he stood up to IBAMA did they prosecute him.

His case hasn't been solved yet. He did a short stint in prison, but thinks the worst is behind him. Anyway, he is no longer in the deforestation business, he says. He has his grocery store and a small ranch. His kids are in college.

Before I can ask him anything else, he looks at his watch and tells me he has to leave. He puts his hand on my shoulder and thanks me for visiting Novo Progresso. He is not the king of deforestation, he tells me. The media here, as in the United States, print a lot of false news.

Soot falls from the sky

A few months later, I receive a text message from a Novo Progresso breeder. Farmers conspire on WhatsApp to set fire to the forest along BR-163. The local newspaper quotes a rancher who says, "We have to show the president that we want to work. " The only way to do that, they say, is to clear the forest. They declare August 10 "Fire Day. "

A few days later, more than 1500 kilometres away, the sky darkened in São Paulo at 3pm. "Imagine how much you have to burn to create that much smoke," says journalist Shannon Sims.

Soot falls from the sky. Massive plumes of smoke are captured by the European Space Agency. At the end of August, 80,000 fires ravaged the forest.

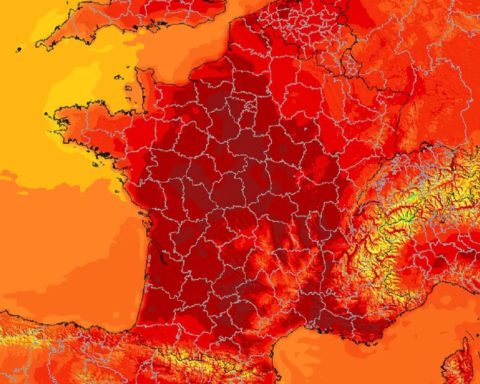

The President of the French Republic, Emmanuel Macron, says it is a global crisis. "Our house is burning," he tweets. A few days later, at the G7 summit, a $20 million aid package is offered to Brazil to help stop the fires. President Bolsonaro rejected it, saying that the Amazon is Brazil's business and that any attempt to interfere is tantamount to colonialism.

Gabriel is back in Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon. He is traveling along the Rio Negro, a major tributary of the Amazon, and sends me a picture of the fire-darkened sky over a national park. The Brazilian news reports that most of the smoke comes from fires burning near Novo Progresso, he tells me. The nun I met along the Trans-Amazon Highway texted me that it is difficult to breathe where she lives, but this is usual during the dry summer months. That's when the farmers always burn the forest.

There is a hint of resignation in his text, and I feel that the attempts by celebrities and world leaders to help, however well intentioned, are futile. I think back to one of my last days at Novo Progresso and what Menezes, the head of the rural union, told me. "We will preserve our way of life," he said. Any attempt to stop them from clearing the forest would come up against force.

Jesse Hyde...big Rolling Stone reporter. Translation and editing UP' Magazine