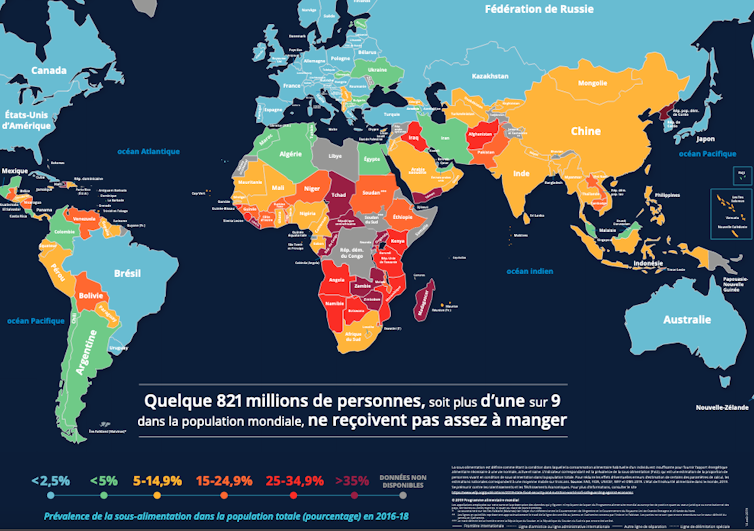

Food has been on the international agenda since the end of World War II. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 unambiguously proclaims the right to food in Article 25. This right was reiterated and specified in 1966 in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. In 2015, the United Nations dedicated one of the Sustainable Development Goals to it: the elimination of hunger by 2030. And yet, nearly one billion people, i.e. one billion people in the world, are still hungry. one in nine people...is suffering from malnutrition.

According to the figures In recent years, the number of undernourished people has been increasing over the past three years. Hunger affects 821 million people. Globally, malnutrition is responsible for one third of deaths among children under five years of age.

Why such a failure? What solutions are available today? Our recent work are making the following observation: you have to stop treating food like any other commodity.

A new approach to food design

For many decades, our societies have treated food as a commodity, that is, as a commodity that is traded on a market. On the one hand, the markets of the hyper-concentrated and highly capital-intensive food industry are in no way geared towards meeting basic needs. Secondly, international law suffers from legal contradictions. On the one hand, the right to food is proclaimed as a fundamental human right. On the other hand, institutions relating to world trade (GATT, WTO) have missions that are contrary to this individual right.

Thus social" rights remain today "second" rights. The right of ownership in its exclusive form, like that derived from the "free trade" enshrined in free trade treaties, in fact exercises primacy over social rights.

Why not enjoy unlimited reading of UP'? Subscribe from €1.90 per week.

Finally, the subject of international law is not the person but the national state, which is "sovereign" in the application of the rules to which it is supposed to submit. It can, therefore, escape the constraints to which it is supposed to have adhered by signing international treaties and conventions (e.g. climate commitments).

This posture has led to the massive exclusion of populations from access to essential food items.

Food, a common good?

This situation explains why fresh thinking are in the process of being affirmed: that of making food a common good. The common goods in the definition proposed by a Italian jurist's commission are "things that express functional utility to the exercise of fundamental rights and to the free development of the person". Consequently, and as such, they "must be protected and safeguarded by the legal system, including in the interest of future generations".

This new discourse is animated by multiple actors. It calls for the creation of conditions to ensure that access to food can be guaranteed for all people, starting with the most deprived.

This approach does not contradict the vision of the right to food. It complements it. Making food "a common good" means thinking about the conditions for the institutionalization of this right.

And concretely?

First of all, it is a question of overcoming the illusion that the realization of the right to food can be based on the "good will" of States, which are moreover subject to the defence of multiple rights and particular interests. This means promoting multiple initiatives, particularly from civil society.

This is not utopia. Three examples of such initiatives (Nutriset, Misola and Nutri'zaza) can guide our thinking.

The Norman company NutrisetThe company was founded in 1986 and is now the world market leader in ready-to-use therapeutic foods. It has developed a product to combat acute malnutrition, Plumpy'Nut, which has never before been effective. Its "form" (a concentrated paste) has made it possible to distribute it outside health centers, facilitating access for populations.

Misola is a French association that has registered a trademark on a food supplement deployed in West Africa to prevent malnutrition in young children under the age of five.

To fight against disinformation and to favour analyses that decipher the news, join the circle of UP' subscribers.

The flour is made entirely from locally grown ingredients and is produced in the villages themselves. The Misola trademark, registered by the association, is given free of charge to any user who undertakes to respect strict specifications in the production process.

Nutri'zaza is a social enterprise under Malagasy law engaged in the fight against chronic malnutrition in Madagascar. Its objectives of social utility are affirmed in its statutes. It is inspired by several great traditions: those of the social and solidarity economy, social business and the mission-oriented companies. These are new forms of business enterprises which are defined in the articles of association, in addition to profit-making, by a social or environmental purpose.

Thus, the power of capital can be marginalized to promote the company's corporate purpose. Shareholders may be remunerated, but only up to the amount of capital invested. An ethics and supervisory committee is in charge of ensuring compliance with the objectives and the impact of its action.

Three considerations

For these entities to be considered as contributing to the right to food, three major considerations must be taken into account.

The first relates to the conditions (pricing policies, manufacturing and distribution arrangements) under which food goods are physically made available. From this point of view, both Misola and Nutri'zaza, by making available a locally produced and cheaply distributed food supplement, are important actors in making food a common good.

In the case of Nutriset, the very high price of the product makes its access entirely dependent on the ability of international organisations to purchase and distribute it. Despite its contribution, the "Nutriset model" therefore has serious limitations in its approach to access.

The second consideration is a social one. It relates to the way in which the initiatives deal with the intellectual property issues of the products they develop. Everything here revolves around the way in which the use of the various attributes of property rights is (or is not) put at the service of the search for the common good.

The Nutriset and Misola initiatives provide opposite cases here. In spite of its contribution, Nutriset has been out of the process of institutionalizing access since it has patented and protected its invention by various means.

On the other hand, Misola, by transferring the Misola brand subject to the respect of the association's charter, has been able to innovate strongly: it uses intellectual property as an instrument for spreading know-how and guaranteeing quality for food produced in the villages themselves.

Finally, the third consideration is based on the corporate form of the entities. Misola, an associative enterprise that locally promotes women's cooperatives for the production of its food supplement, or Nutri'zaza, a "social" enterprise that is statutorily prohibited from paying out profits, illustrate the possibility of designing and deploying innovative corporate forms that are geared towards the objective of promoting access to the most disadvantaged.

The path towards truly inclusive food seems to exist through this type of initiative. But only the construction of specific institutions, legally and economically designed to guarantee access to resources, i.e. to make these resources common goods, will make it possible to achieve the objectives pursued.

Benjamin Coriat...Professor of Economics, University of Paris 13 - USPC and Stephanie LeyronasResearch Fellow, Commonwealth Research Officer, French Development Agency (AFD)

Nicolas Le Guen (AFD), Nadège Legroux (AFD) and Magali Toro (nutrition/health research officer) contributed to this article.

This article is republished from The Conversation, editorial partner of UP' Magazine. Read theoriginal paper.

![]()