La politique européenne n’est pas simplement divisée entre la gauche et la droite, et entre les attitudes pro et anti-intégration européenne, mais entre différentes « tribus de crise » dont les membres ont été traumatisés par des événements clés. Au cours de la dernière décennie, l’Europe a connu et connaît encore des crises économiques, sécuritaires, sanitaires, climatiques et migratoires qui ont créé des identités politiques à travers et entre les pays. Il s’est ainsi formé une atmosphère d’anxiété où 6 citoyens européens sur 10 estiment que leurs pays respectifs vont dans la mauvaise direction. Or l’analyse politique dominante ne comprend pas à leur juste dimension les traumatismes existentiels concurrents qui traversent les différents États membres et les opposent. Pourtant, ces traumatismes sont susceptibles de dominer près de 20 élections à travers le continent en 2024.

À l’approche des élections européennes de cette année, les dirigeants politiques tentent de déterminer les questions qui définiront la prochaine phase de la politique européenne. Le clivage gauche-droite est un indicateur moins utile du comportement électoral qu’il ne l’était autrefois, notamment parce que, dans de nombreux pays, les partis des deux côtés de l’échiquier politique convergent sur de nombreuses questions clés, de l’immigration aux dépenses sociales. Le clivage entre les partis pro et anti-européens risque également d’être un mauvais guide, contrairement aux élections de 2019, qui ont eu lieu alors que le Brexit était encore en cours de négociation : la plupart des partis d’extrême droite ont renoncé à leurs promesses de quitter l’Union européenne, tandis qu’aucun dirigeant ne parle d’une Europe fédérale. Dès lors, comment envisager l’avenir de la politique européenne ?

« L’analyse politique dominante sous-estime les traumatismes existentiels concurrents qui traversent les différents États membres et les opposent ».Pour répondre à cette question, le Conseil européen des relations étrangères a commandé une enquête dans 11 pays européens : L’Allemagne, la France, la Pologne, l’Italie, l’Espagne, le Danemark, la Roumanie, le Portugal et l’Estonie, pays membres de l’UE, et deux pays européens non-membres de l’UE, la Grande-Bretagne et la Suisse. L’enquête a permis de comparer le soutien des partis aux attitudes dans différents domaines politiques et aux attitudes à l’égard des performances des institutions de l’UE et des gouvernements nationaux. Les rapporteurs de cette étude observent d’emblée que « l’analyse politique dominante sous-estime les traumatismes existentiels concurrents qui traversent les différents États membres et les opposent ».Polycrise

Au cours des 15 dernières années, l’Europe a connu cinq crises majeures. La crise climatique a forcé les Européens à imaginer un monde en péril. La crise financière mondiale a conduit les Européens à douter que leurs enfants jouiraient d’un niveau de vie supérieur au leur. La crise migratoire a déclenché une panique identitaire centrée sur les questions du multiculturalisme et de la signification des États-nations. La pandémie de Covid-19 a mis en évidence la vulnérabilité de nos systèmes de santé dans un monde globalisé. Et la guerre en Ukraine a brisé l’illusion qu’une guerre majeure ne reviendrait jamais sur le continent européen. Les auteurs de l’étude font observer que ces cinq crises ont plusieurs points communs : « elles ont été ressenties dans toute l’Europe, bien qu’à des intensités différentes ; elles ont été vécues comme une menace existentielle par de nombreux Européens ; elles ont eu un impact considérable sur les politiques gouvernementales ; et elles sont loin d’être terminées. »

Selon les groupes sociaux, une crise joue généralement un rôle dominant par rapport aux autres.Le terme « polycrise » est apparu pour suggérer que les cinq crises se déroulent plus ou moins simultanément, que le choc de leur interaction cumulative est plus écrasant que leur somme, et que ces différentes crises n’ont pas de cause unique ni de solution universelle. Cependant, une caractéristique de la polycrise dont on ne parle pas assez est que, pour différentes sociétés et différents groupes sociaux, une crise joue généralement un rôle dominant par rapport aux autres. La crise des Gilets jaunes l’a montré, en France, en opposant ceux qui s’inquiètent de la fin du mois (crise économique) à ceux qui s’inquiètent de la fin du monde (crise climatique). C’est dans ce sens que les auteurs de l’étude affirment que « chacun veut sa propre crise ».Cinq tribus pour cinq crises

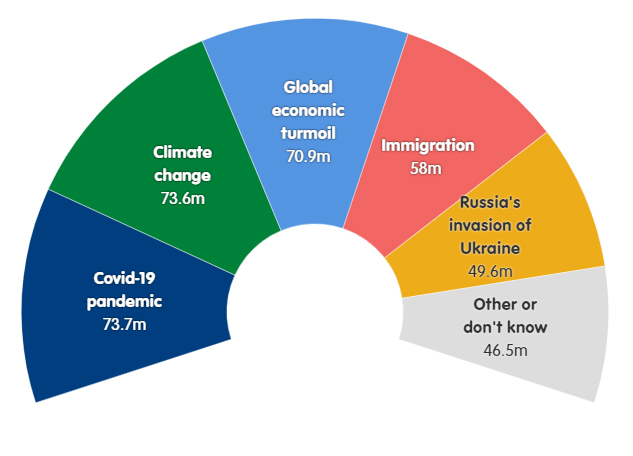

La principale conclusion de l’étude est qu’aucune crise ne domine l’imaginaire collectif européen. Le changement climatique, la guerre en Ukraine, le Covid-19, l’immigration et la crise économique mondiale – chacun de ces cinq problèmes possède son propre groupe de citoyens qui citent une crise particulière comme étant celle qui les préoccupe le plus. Ces groupes sont inégalement répartis entre les différentes générations et entre les différents pays.

Sur les 372 millions d’habitants de l’UE en âge de voter, environ 74 millions de personnes citent le climat, 73 millions le covid-19 et 70 millions la crise économique comme leur principale préoccupation. Viennent ensuite 59 millions de citoyens de l’UE qui sont principalement préoccupés par l’immigration et 49 millions qui se concentrent sur l’invasion de l’Ukraine par la Russie. Environ 47 millions de personnes ont du mal à s’associer à l’une ou l’autre des cinq crises.

Ces cinq groupes sont les différentes « tribus de crise » de l’Europe. Comme toutes les tribus, elles partagent une histoire d’origine commune. Elles partagent des formes de langage et des sensibilités. Elles ont des totems et des chefs, mais aussi des fractures internes.

Géographie des tribus européennes de crise

Les tribus de crise ne sont pas confinées à une seule nation et sont inégalement réparties en Europe.

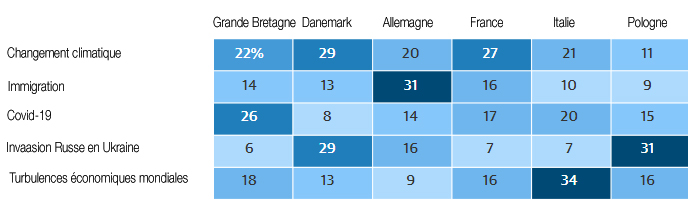

L’Allemagne est le seul pays où le plus grand nombre de personnes désignent l’immigration comme la question qui les préoccupe le plus ; les récentes arrivées de migrants ont peut-être ravivé les souvenirs de 2015, lorsque le pays a accueilli un million de personnes, dont des Syriens fuyant Bachar el-Assad. La France et le Danemark sont les seuls pays de l’UE dont les citoyens considèrent le changement climatique comme la crise la plus importante. Les citoyens italiens et portugais soulignent les turbulences économiques des quinze dernières années ; la crise de l’euro aura laissé une longue traînée dans ces pays. En Espagne, en Grande-Bretagne et en Roumanie, les citoyens considèrent la pandémie de covid-19 comme le problème qui les a le plus affectés. Les Estoniens, les Polonais et les Danois considèrent la guerre en Ukraine comme la plus transformatrice des crises.

Basé sur les réponses à la question : « Parmi les sujets suivants, lequel a, au cours de la dernière décennie, le plus changé la façon dont vous envisagez votre avenir ? »[adning id="34073" no_iframe="1"]

Si certaines crises occupent une place importante dans l’imaginaire national, d’autres sont à peine évoquées. Par exemple, les préoccupations des Estoniens à l’égard de la guerre en Ukraine et de l’économie dominent tout. L’immigration n’est la principale source d’inquiétude que pour une poignée de Polonais, d’Estoniens, de Roumains et de Portugais, même si les réfugiés d’Ukraine continuent d’arriver. Les Allemands ne semblent pas encore, au moment où l’étude a été réalisée, préoccupés par les difficultés économiques. En France, en Grande-Bretagne, en Italie et en Espagne, un nombre presque scandaleusement bas de personnes désignent la guerre en Ukraine comme la crise qui a le plus d’impact sur la façon dont ils envisagent leur avenir.

Démographie des tribus de crise

Les crises divisent également les Européens en fonction de l’âge, du sexe et du niveau d’éducation.

Les jeunes sont plus concernés par la crise climatique que par les autres crisesSans surprise, les jeunes sont plus concernés par la crise climatique que par les autres crises, 24 % des 18-29 ans étant particulièrement inquiets. En Grande-Bretagne, en France, en Allemagne, au Danemark et en Suisse, les jeunes ont tendance à donner la priorité aux questions climatiques. Toutefois, dans d’autres pays, les jeunes se concentrent davantage sur des problèmes tels que la crise économique mondiale (en Estonie et au Portugal), la guerre en Ukraine (en Pologne) et le covid-19 (en Espagne et en Roumanie). En revanche, si l’on considère l’ensemble des pays, les plus de 70 ans sont les plus mobilisés par la guerre en Ukraine (27 %) et se concentrent davantage sur l’immigration que les jeunes générations. Le Covid-19 est la seule crise qui, dans toute l’Europe, ne semble pas préoccuper une génération plus qu’une autre.En termes d’éducation, les personnes les plus instruites des 11 pays européens considèrent le changement climatique comme la crise la plus transformatrice, légèrement avant les problèmes économiques. À l’inverse, les personnes moins diplômées sont plus susceptibles de se sentir affectées par l’immigration. Cette tendance est observable au Danemark, en France, en Allemagne, en Grande-Bretagne, en Italie et en Pologne.

Partis politiques et tribus de crise

Les crises européennes font vivre aux gens des expériences dont l’impact ne s’inscrit pas clairement dans les divisions gauche-droite, pro-immigration ou anti-immigration, establishment ou populisme. Au contraire, toutes ces expériences sont marquées par un fort sentiment de déception résultant des insuffisances des gouvernements en matière de gestion des crises – et par la crainte que les crises ne reviennent.

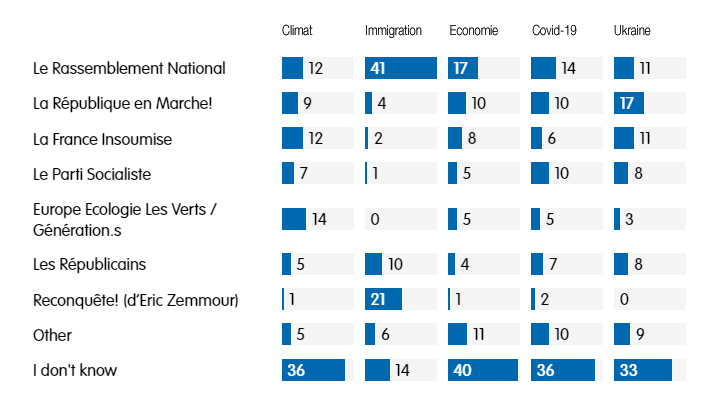

Les crises climat et immigration prennent la forme d’un affrontement entre deux « rébellions de l’extinction ».Les deux crises qui dominent les médias et le débat politique à l’approche des élections sont le climat et l’immigration. Et la lutte entre les deux tribus qui suivent ces questions de plus près prend selon les auteurs de l’étude la forme d’un affrontement entre deux « rébellions de l’extinction ». Alors que les défenseurs du climat craignent l’extinction de la vie humaine et d’autres formes de vie, les militants anti-immigration craignent la disparition de leur nation et de leur identité culturelle.Ceux qui considèrent l’immigration comme la crise la plus grave voteront très probablement pour des partis de centre-droit ou d’extrême-droite. Les données montrent qu’en Allemagne, cela signifie une forte probabilité de voter pour l’AfD ; en France, pour le Rassemblement national de Marine Le Pen ou Reconquête d’Éric Zemmour.

L’inverse est vrai pour le climat, où ceux qui considèrent qu’il s’agit de la question la plus importante, affluent massivement vers les partis verts ou des partis tels que les socialistes en Espagne ou la Coalition civique et la Gauche en Pologne.

Les auteurs de l’étude font remarquer que ces deux tribus de crise connaissent des dynamiques très différentes une fois que leurs partis préférés sont au pouvoir. Lorsque la tribu de l’immigration voit les partis de droite au pouvoir, ses membres ont tendance à se détendre sur la question. En Italie, l’immigration ne figure étonnamment pas parmi les préoccupations de nombreux électeurs : seuls 10 % de la population du pays et 17 % des partisans des Frères d’Italie (Fratelli d’Italia, le parti de la première ministre italienne, Giorgia Meloni ) la décrivent comme leur crise la plus transformatrice, même si les Frères d’Italie ont été élus sur un programme résolument anti-immigration. Une situation similaire a été observée en Pologne avec Droit et Justice, avant que ce parti ne perde les dernières élections générales. Cela rappelle l’évolution de l’opinion publique en Grande-Bretagne, où l’attitude des électeurs à l’égard de l’immigration s’est améliorée après le référendum sur le Brexit, alors même que le nombre de personnes arrivant sur le territoire augmentait.

Les électeurs peuvent percevoir l’élection d’un gouvernement d’extrême droite comme la réponse aux craintes liées à l’immigration mais ils ne considèrent pas que l’urgence climatique est terminée avec l’élection des Verts.La tribu du climat se comporte de manière inverse. Les sondages en Allemagne montrent que les gens continuent de s’inquiéter de la crise climatique même lorsque leur gouvernement a un programme climatique solide ; ils ne considèrent pas que le problème est résolu. En bref, les électeurs peuvent percevoir l’élection d’un gouvernement d’extrême droite comme la réponse aux craintes liées à l’immigration – même si peu de choses changent en réalité – mais ils ne considèrent pas que l’urgence climatique est terminée avec l’élection des Verts.Pour les autres crises, la dynamique est tout à fait différente. Les membres de la tribu de l’économie ne sont pas unis par une politique de gauche ou de droite, mais par une position antigouvernementale. Ils détestent souvent le gouvernement au pouvoir, quelle que soit son orientation politique. Par exemple, en Italie, 31 % des membres de ce groupe déclarent ne pas avoir l’intention de voter lors des prochaines élections européennes, et 16 % ne savent pas comment ils voteront. En France, 40 % des membres de ce groupe ne savent pas quel parti reflète le mieux leurs idées.

Cela pourrait s’expliquer par l’absence de différence majeure entre les politiques d’austérité adoptées par les gouvernements de droite ou de gauche en 2009-10. Plutôt que de renforcer le clivage gauche-droite, la crise économique pourrait avoir réduit son importance. Au cours des différentes crises, les pays qui avaient des gouvernements de centre-gauche en place les ont remplacés par des partis de centre-droit, et vice-versa. Ainsi, les membres de la tribu de la crise économique sont en quelque sorte des électeurs protestataires classiques.

Les membres de la tribu de la guerre et de la tribu de la pandémie sont beaucoup plus favorables au gouvernement en place. La pandémie a plutôt affaibli que renforcé les partis populistes en Europe, du moins à court terme. Mais à long terme, les choses pourraient évoluer différemment si l’on en croit les récentes élections dans plusieurs États membres de l’UE, comme aux Pays-Bas, en Slovaquie et dans certaines régions allemandes. Ces élections ont révélé l’existence de groupes anti-confinement, anti-vax et anti-guerre nés à l’époque du covid-19 et revigorés depuis l’invasion de l’Ukraine par la Russie. Il semble qu’il s’agisse d’identités politiques fortes.

L’examen de la répartition des tribus entre les partis montre que certaines tribus ont une base politique très concentrée. Cela signifie, par exemple, que l’extrême droite pourrait utiliser sa crédibilité en matière d’immigration pour toucher d’autres électeurs en mettant l’accent sur le climat, le coût de la vie et d’autres questions plus générales. Il en va de même pour le climat, où les jeunes sont très engagés et susceptibles de constituer une base électorale solide si les partis politiques parviennent à faire des élections européennes un référendum sur le sujet. Bon nombre des autres partis traditionnels sont des partis « attrape-tout », qui se concentrent sur plus d’une crise ou sur différentes combinaisons de crises. Ceux-ci pourraient rencontrer des difficultés à inciter leurs partisans à voter aux élections européennes, dont le taux de participation est traditionnellement faible.

Tribus en crise et projet européen

Jean Monnet disait : « L’Europe se forgera dans la crise et sera la somme des solutions adoptées à ces crises« . Mais que se passe-t-il lorsque les citoyens commencent à croire que ni leur propre pays ni l’UE ne seront en mesure de résoudre les crises ?

Les électeurs pourraient être davantage motivés par l’angoisse des crises passées que par l’espoir d’un avenir meilleur.C’est dans ce contexte que s’inscrivent les prochaines élections du Parlement européen, où de nombreux citoyens pourraient être davantage motivés par l’angoisse des crises passées que par l’espoir d’un avenir meilleur. Lors des dernières élections, la lutte centrale opposait les populistes qui voulaient tourner le dos à l’intégration européenne et les partis traditionnels qui voulaient sauver le projet européen du Brexit et de Donald Trump. Mais les prochaines élections porteront sur des projections plutôt que sur des projets. Il s’agira d’une compétition entre les peurs rivales de la hausse des températures, de l’immigration, de l’inflation et des conflits militaires.Ces cinq crises sont importantes à l’approche des élections, mais elles ont toutes un potentiel de mobilisation différent. La crise économique finit souvent par démoraliser les gens plutôt que de les motiver à se rendre aux urnes. Les auteurs de l’étude suggèrent que les partis de l’establishment qui font campagne sur l’économie pourraient avoir du mal à tirer leur épingle du jeu.

Dans les mois qui ont suivi l’invasion de l’Ukraine par la Russie, la guerre a accaparé l’attention du continent comme aucune autre question. Mais les citoyens ne perçoivent pas nécessairement qu’il s’agit d’une crise existentielle à laquelle est confrontée l’Europe dans son ensemble ; nombreux sont ceux qui considèrent que la guerre n’est une crise existentielle que pour l’Ukraine et certains de ses voisins immédiats. En effet, la plupart des membres de la tribu de la guerre pensent que l’OTAN et l’UE ne sont pas engagées dans une guerre contre la Russie. Un fossé a peut-être commencé à se creuser entre les élites européennes, qui continuent de parler de tout faire pour soutenir Kiev, et leurs électeurs, qui se concentrent davantage sur d’autres crises. La guerre Israël-Hamas, qui a débuté après le déroulement du sondage sur le terrain, aura probablement un impact plus fort sur la politique européenne dans certains pays que la guerre Russie-Ukraine, mais il ne serait pas surprenant que ses retombées profitent surtout à la tribu de l’immigration, perturbant ainsi la politique nationale.

L’urgence climatique et les migrations vont façonner les élections de cette année.C’est le climat et la migration qui semblent susceptibles de façonner les élections de cette année, comme le suggère le résultat des récentes élections générales aux Pays-Bas, qui ont placé un parti anti-immigration en tête des sondages et l’alliance de gauche pro-climat menée par Frans Timmermans en deuxième position. La tribu du climat est la tribu la plus favorable à l’UE. La nature de cette crise exige une vaste coopération internationale, de sorte que cette tribu pourrait bien considérer que l’UE est plus à même d’agir en faveur du climat que les États nationaux.Contrairement à la tribu climatique, les membres de la tribu migratoire ont tendance à être plus sceptiques à l’égard de l’UE. Ils constituent le seul groupe au sein duquel une majorité s’attend à ce que l’Union s’effondre au cours des 20 prochaines années. Ses membres sont les plus susceptibles de voter pour des partis de droite ou d’extrême droite. Ils sont les moins favorables aux énergies renouvelables (bien qu’une majorité y soit encore favorable) et les plus grands partisans de l’énergie nucléaire et des combustibles fossiles. Nombre d’entre eux déclarent préférer un dirigeant qui défend l’indépendance de leur pays plutôt qu’un dirigeant qui s’engage dans la coopération internationale.

Une élection de projection

À l’approche de l’élection du Parlement européen de 2019, beaucoup craignaient que les partis populistes et anti-européens capitalisent sur la peur de l’immigration des électeurs pour gagner une minorité de blocage au sein de l’organe législatif de l’UE. L’ancien stratège en chef de la Maison Blanche sous Trump, Steve Bannon, espérait qu’il s’agirait du troisième triomphe d’une internationale illibérale après le Brexit et l’élection de Trump. Mais dans les faits, ces partis populistes ont échoué et il y a eu une mobilisation surprenante d’électeurs pro-européens qui voulaient sauver l’UE de la désintégration.

Les élections européennes seront une bataille pour la suprématie entre les différentes tribus de crise de l’Europe.Les partis traditionnels ont peut-être réalisé qu’ils auront du mal à faire des prochaines élections un référendum sur l’avenir du projet européen. Par conséquent, ils examinent de plus en plus les deux crises les plus mobilisatrices – l’immigration et le climat – et développent des stratégies qui pourraient bouleverser les débats politiques européens qui caractérisaient ces crises. L’urgence climatique a traditionnellement été la cause libérale européenne par excellence, comme l’illustrent les initiatives menées par la Commission européenne telles que net zero, le mécanisme d’ajustement carbone aux frontières et Fit for 55. Aujourd’hui, cependant, le climat est en train d’être « renationalisé », alors que le contrecoup anti-vert devient un puissant cri de ralliement pour la droite anti-establishment.L’immigration, quant à elle, était la cause nationaliste par excellence, mais les institutions de l’UE et les gouvernements pro-européens sont en train d’européaniser la question. L’establishment de l’UE s’en est emparé dans le but de trouver une solution européenne commune, notamment en adoptant une politique européenne commune en matière d’immigration et d’asile.

Les décisions prises par les dirigeants européens dans les mois à venir sur les autres crises façonneront également l’avenir de l’Europe. Les États membres devront répondre à des questions sur l’adhésion de l’Ukraine à l’UE, le soutien à l’effort de guerre, le budget du « Green Deal » européen et les détails d’une politique d’asile commune.

« Chacune des cinq crises de l’Europe aura plusieurs vies, concluent les auteurs, mais c’est dans les urnes qu’elles vivront, mourront ou seront ressuscitées. Les élections européennes ne seront pas seulement une compétition entre la gauche et la droite, les eurosceptiques et les pro-européens, mais aussi une bataille pour la suprématie entre les différentes tribus de crise de l’Europe. De nombreux électeurs s’efforceront d’empêcher le retour d’une crise qui leur est propre ».

Cette étude a été menée à l’initiative du Conseil européen des relations étrangères (ECFR) en association avec la Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian, le Think Tank Europa et l’International Center for Defence and Security. Elle est basée sur un sondage d’opinion réalisé en septembre et octobre 2023 auprès de populations adultes (âgées de 18 ans et plus) dans 11 pays européens (Allemagne, Danemark, Espagne, Estonie, France, Grande-Bretagne, Italie, Pologne, Portugal, Roumanie et Suisse). Le nombre total de répondants était de 15 081.

Les sondages ont été réalisés par Datapraxis et YouGov au Danemark (1 040 ; 26 septembre – 2 octobre), en France (2 079 ; 26 septembre – 6 octobre), en Allemagne (2 036 ; 26 septembre – 5 octobre), en Grande-Bretagne (2 043 ; 26 septembre – 2 octobre), en Italie (1 530 ; 26 septembre – 5 octobre), en Pologne (1 069 ; 26 septembre – 4 octobre), le Portugal (1 050 ; 26 septembre – 4 octobre), la Roumanie (1 104 ; 26 septembre – 3 octobre), l’Espagne (1 014 ; 26 septembre – 3 octobre), et la Suisse (1 103 ; 26 septembre – 3 octobre) ; et par Datapraxis et Norstat en Estonie (1 013 ; 26 septembre – 9 octobre).