Qu’est-ce qu’un philosophe peut-il bien avoir à nous dire en pleine crise pandémique ? Sans doute pas grand-chose si l’on estime que la conversation est exclusivement réservée aux scientifiques s’efforçant de fournir des réponses froides à toutes les questions de l’homme – alors que chez le philosophe, il semble plutôt y avoir multiplication des questions et diminution du nombre de réponses. En revanche, si l’on envisage cette crise de manière plus holistique, c’est-à-dire dans sa globalité, il me semble alors qu’un certain propos philosophique – plutôt athéorique, sensible au primat de la pratique et davantage interprétatif que créatif – peut apporter un précieux éclairage du moment que l’on a affaire à la grande complexité de l’homme vivant.

Dans ces conditions, Clint Witchalls et Lionel Cavicchioli attirent notre attention dans leur article du 10 mars 2020 sur le fait que différents « auteurs ont […] cherché à replacer l’épidémie [pandémie, il faut ici préciser, depuis le 11 mars 2020] dans le contexte d’autres pandémies », mais aussi vis-à-vis de l’impact « croissant du COVID-19 (le nom officiel de la maladie) sur l’économie mondiale, sur ce qu’il révèle de la fragilité des chaînes logistiques, sur la manière dont il rend la science plus ouverte (et sur les risques concomitants que cela comporte), ainsi que sur les progrès en matière de développement d’un vaccin ».

On peut aussi mentionner la réflexion de Giorgio Agamben qui inscrit la pandémie dans le contexte politique récent : pour le théoricien italien, il « semblerait que, le terrorisme étant épuisé comme cause de mesures d’exception, l’invention d’une épidémie puisse offrir le prétexte idéal pour les étendre au-delà de toutes les limites ». Or force est de constater qu’il y a un aspect qui est paradoxalement négligé dans les discours tout en constituant le cœur de la crise : il est ici question d’une réflexion sur l’expérience de la mort qui occupe dans l’histoire de l’humanité une position tout à fait centrale depuis la nuit des temps. Elle revient nous hanter.

Autrement dit, c’est comme si on n’entendait plus vraiment bourdonner à notre oreille le murmure de la mort, on ne l’entend à présent que parce qu’une pandémie semble nous remettre la mort en pleine face.

C’est en tout cas ce qui m’apparaît se présenter devant nous – par-delà toutes les considérations théoriques des experts, dans la pratique, jour après jour – depuis les début de l’année 2020 où « l’on a commencé à entendre parler d’un nombre inquiétant de cas de pneumonies à Wuhan, en Chine, causés par un mystérieux nouveau « coronavirus » [ : à] ce moment-là, elle se propageait en Chine, et quelques personnes avaient été testées positives en Thaïlande, en Corée du Sud et au Japon, comme nous rappellent les deux auteurs de l’article intitulé « Coronavirus : le point sur la couverture internationale de The Conversation ».

À cet effet, l’interprétation que j’avance s’enracine à mon avis dans un mouvement bien plus profond et ancien de la modernité occidentale, soit une certaine marche des Lumières annonçant la mort de la mort :

Ce fut, pour notre conscience, un événement bien plus important qu’une simple transformation de l’image de la mort telle qu’elle nous est parvenue à travers des millénaires de mémoire humaine, soit à travers l’interprétation qu’en donnent les religions, soit à travers les formes d’organisation de la vie de l’homme. Cet évènement, spécifique de notre époque, est bien plus radical encore : il s’agit de l’effacement de l’image de la mort dans la société moderne. Cela, notre conscience l’exige manifestement. On pourrait le définir comme un renouveau du mouvement des Lumières ; mais ces nouvelles Lumières, cette fois, touchent l’ensemble des couches de la population et font de la maîtrise technologique de la réalité, obtenue grâce aux performances éclatantes des sciences naturelles et au système d’information moderne, le fondement de toute chose. Ce nouveau mouvement des Lumières a engendré une démystification de la mort (2).

Toutefois, on constate qu’au sein de l’élan des Lumières portées par le succès des sciences – surtout des mathématiques et de la physique – expliquant des phénomènes auparavant inexplicables – par exemple, par une science oscillante come la métaphysique traditionnelle avant la réforme d’Emmanuel Kant –, la démystification de la mort se situe, par extension naturelle, dans la continuité d’une démystification de la vie.

Qu’est-ce que cela veut dire concrètement ? J’entends par là le fait qu’aux yeux des scientifiques, l’introduction du nouveau dans la cours du monde, l’apparition de la vie dans l’univers, n’a plus aucune dimension prodigieuse ou miraculeuse en tant que « produit d’un jeu incalculable du hasard [; la science] réussit à nommer des causalités scientifiques décisives qui, dans un processus progressif, compréhensible dans ses grandes lignes, ont conduit à la naissance de la vie sur notre planète ainsi qu’à toutes les évolutions qu’elle a subies par la suite » (3). Or, à partir de là, l’expérience de la mort dans la vie de l’homme semble avoir aussi glissé sur cette pente glissante des Lumières : sont ici en grande partie responsables la révolution industrielle et les grandes transformations sociales qui ont accompagné ce qu’on pourrait qualifier de processus visant à rompre tous les liens, à l’échelle macro comme micro, pour atomiser de bord en bord ce qui autrefois était lié.

Au sein de cette nouvelle société atomisée, l’horizon de la mort est subtilement écarté du quotidien :

Non seulement en faisant disparaître la procession funéraire hors du paysage urbain – ce défilé où chacun ôtait son chapeau devant la majesté de la mort. Mais également en rendant la mort effectivement anonyme dans les cliniques modernes, engendrant ainsi un bouleversement bien plus profond encore. La disparation de la représentation publique de cet événement va de pair avec l’éloignement du mourant hors de son milieu familial et familier ainsi qu’avec sa séparation d’avec ses parents (4).

C’est comme si l’expérience de la mort, l’événement de la mort pour employer le vocabulaire gadamérien, est tout à fait intégrée – absorbée en quelque sorte – dans le grand mécanisme technologisant propre à la production industrielle et à sa cadence aliénante. Dès lors, au même titre que les nombreuses autres activités économiques de l’homme moderne, la mort s’insère dans cette trame en tant qu’une autre activité de production – avec ses parts de marché à conquérir, épousant le modèle de l’offre et de la demande, et surtout comme sphère soumise aux lois du marché et de la concurrence commerciale – parmi tant d’autres.

Cependant, l’horizon de la mort représente dans la vie de l’homme une expérience tout à fait unique. Non seulement qu’elle se situe sur un autre plan – elle introduit, jusqu’à un certain niveau, au même titre peut-être que le langage, un devenir humain de l’homme –, mais elle est aussi sans doute « la seule expérience qui marque aussi nettement les limites posées à la maîtrise de la nature que la science et la technique ont rendue possible » du moment que « [m]ême les immenses progrès techniques que l’on a réalisés dans le prolongement souvent artificiel de la vie ne font que démontrer la limite absolue de notre savoir-faire » (5). Ce n’est donc pas anodin si le transhumanisme, en tant qu’entreprise dangereuse visant à nier la finitude de l’homme et donc ce qui en fait de lui un, s’est donné comme principale cible la mort : plus précisément, la mort de cette mort. C’est ultimement en empruntant cette voie que les transhumanises pensent pouvoir aller par-delà la finitude de l’homme, vers une soi-disant vie infinie de l’homme : or, cela concernera naturellement que les plus riches.

Revenons un instant à notre question de départ : qu’est-ce qu’un philosophe peut avoir à nous dire dans ces conditions ? À mon avis, sa contribution est ici plus marquée et nette. Plus précisément, il convient pour le philosophe de notamment contrer l’influence néfaste de la dangereuse utopie transhumaniste. Dangereuse, parce que toute utopie en tant que guide de l’action politique – c’est-à-dire débordant un cadre imaginaire, car seulement à l’intérieur de ce cadre restrictif elle apporte une certaine valeur en tant qu’acte littéraire de création – peut se révéler littéralement catastrophique, soit au même titre que l’utopie communiste et fasciste :

La possibilité d’une solution finale – même si nous oublions le sens effroyable que cette expression a acquis pour nous – s’avère une illusion, et une illusion très dangereuse. Car si l’on croît réellement à la possibilité d’une telle solution, alors il ne fait nul doute qu’aucun coût ne serait trop élevé pour y parvenir : rendre l’humanité juste, heureuse, créatrice et harmonieuse à tout jamais – quel prix ne serait-on pas prêt à payer pour cela ?

Pour faire une telle omelette, il n’existe certainement pas de limite au nombre d’œufs que l’on peut casser – c’était là l’idéal de Lénine, de Trotski, de Mao, de Pol Pot, pour ce que j’en sais. Puisque je connais l’unique chemin qui mènera à la solution définitive des problèmes de la société, je sais par où conduire la caravane de l’humanité ; et puisque vous ne savez pas ce que moi je sais, il n’est pas question de vous laisser la moindre liberté de choix, si l’on veut que le but soit atteint. Vous déclarez que telle politique vous rendra plus heureux, ou plus libre, ou vous donnera plus de place pour respirer ; mais je sais que vous vous trompez, je sais ce qui vous est nécessaire, ce qui est nécessaire aux hommes ; et si je rencontre une résistance, due à l’ignorance ou à la malveillance, alors elle devra être brisée, et des centaines de milliers d’hommes périront s’il le faut pour que des millions d’autres soient heureux à tout jamais.

Que voudriez-vous que nous fassions, nous qui avons la connaissance, sinon être prêts à les sacrifier tous ? Certains prophètes armés cherchent à sauver l’humanité, d’autres leur race seulement, à cause de ses qualités supérieures, mais quel que soit le motif, les millions de victimes des guerres et des révolutions – dans les chambres à gaz, les goulags, au cours des génocides : toutes les monstruosités pour lesquelles notre siècle restera gravé dans les mémoires – sont le prix à payer pour la félicité des générations futures. Si votre désir de sauver l’humanité est sérieux, il faut vous blinder le cœur et ne pas regarder à la dépense. […] La seule certitude que nous puissions avoir est celle de la réalité du sacrifice, des mourants et des morts. Mais l’idéal au nom duquel ils meurent reste lointain. Les œufs sont cassés, et l’habitude de les casser s’installe, mais l’omelette reste invisible (6).

Ainsi, si aujourd’hui, après que les grandes visions utopiques et totalitaires de gauche comme de droite se sont effondrées – ces solutions finales qui ont cassés tant d’œufs –, le spectre d’une autre utopie nous hante : celle du transhumanisme présentée encore une fois comme l’unique chemin qui mènera à la solution (technologique) définitive des problèmes de la société, avec une poignée de patrons qui veulent y conduire la caravane de l’humanité.

Or c’est précisément un refus des réponses univoques à la complexité du réel et de l’homme vivant que j’avance. Sur ce point, je m’appuie sur une observation de la part de Kant que Isaïah Berlin tient pour l’un des plus sages commentaires sur la condition humaine : « Aus so krummen Holze, als woraus der Mensch gemacht ist, kann nichts ganz Gerades gezimmert werden », qui en français évoque que « d’un bois si tors que celui dont sont faits les hommes, jamais l’on ne tirera rien de bien droit », ou bien que « dans un bois aussi courbe que celui dont est fait l’homme, on ne peut rien tailler de tout à fait droit » (7).

C’est pour cette raison, il me semble, qu’aucune solution soi-disant parfaite n’est ni possible ni souhaitable dans les affaires humaines : toute tentative va non seulement résulter en un échec, mais surtout en un excès de violence.

Voilà pour l’objection philosophique, définitive il me semble, à l’idée – plus généralement – d’une totalité parfaite, voire d’une solution définitive, au sein de laquelle tous les problèmes de l’homme sont solubles, mais aussi à l’idée – plus précisément – d’une grande solution technologique et transhumaniste à toutes nos questions comme horizon ultime.

Ceci est d’autant plus vrai à l’heure de cette crise pandémique où la fragilité de notre structure économique et politique – surtout en ce qui concerne la fondation qui oscille du château de cartes formant le grand réseau de la mondialisation – nous est tragiquement rappelée : l’expérience de la mort, ce phénomène gênant et épeurant qu’on a voulu balayer de nos pensées, effectue son retour. En allumant la télévision, on nous présente à la minute près l’évolution du nombre de morts à l’échelle nationale comme internationale ; sur les réseaux sociaux, les proches de ceux emportés par la maladie publient des messages pour nous sensibiliser à la rapidité avec laquelle le virus tue ; la peur de la mort introduit un état de panique généralisé et une dose surprenante d’irrationalité chez ceux qui vident les comptoirs des rayons des supermarchés ; dans certains pays on construit des immenses fosses communes et on s’empresse d’y enfouir les morts ; l’imaginaire de la mort ruissèle de manière lente mais constante sous nos pieds. Elle est de retour.

Car l’homme, depuis toujours, mais encore plus depuis la vague des Lumières, peut difficilement concevoir que sa conscience, « cette conscience apte à se projeter dans le futur » comme dirait Gadamer, puisse complément s’éteindre un jour. On est là en présence de quelque chose qui nous empêche de dormir le soir tellement c’est étrangement inquiétant : « [i]l y a comme un rapport profond entre, d’un côté, la conscience de la mort, la conscience de sa propre finitude, c’est-à-dire la certitude que l’on doit mourir un jour et, d’un autre côté, la volonté terriblement forte et impérieuse de ne rien savoir de ce genre de conscience » (8).

Autrement dit, l’homme est garanti d’avoir un futur tant et aussi longtemps qu’il ne conscientise pas qu’en fait il n’a pas de futur. Notre volonté de vivre passe par le refoulement de la mort. Ce rapport si personnel et profondément intime à l’expérience de la mort ne va pas être épargné par les Lumières, bien au contraire :

On peut certainement dire, pour lors, que le monde de la civilisation moderne tente avec zèle et excès de zèle d’amener pour ainsi dire le refoulement de la mort, qui s’ancre dans la vie elle-même, à une institutionnalisation parfaite, et que, pour cette même raison, il relègue l’expérience de la mort totalement en marge de la vie publique (9).

Dans ces conditions, le projet transhumaniste, en un certain sens, s’efforce de prolonger cette marche des Lumières. Cependant, il semble y avoir une différence – peut-être de taille, je n’en sais rien : alors que les hommes des Lumières se contentaient d’écarter la mort du champ immédiat des préoccupations, sans toutefois l’oublier car elle gardait une place marginale – mais une place tout de même –, les tenants du transhumanisme semblent déborder de confiance en espérant son éradication totale, et ce peu importe le coût d’une telle idée.

Or mon pari est le suivant – à vrai dire, peut-être qu’il s’agit plutôt là d’une observation : la crainte devant le mystère de la mort, un certain effroi devant son silence assourdissant et son caractère sacré, ou encore l’étrange expérience d’une séparation aussi radicale avec celle ou celui qui, quelques instants auparavant, était encore en vie, ne peuvent être écartés d’un revers de main. L’expérience de la mort – et un certain rapport de refoulement tout à fait intime et sain à cette dernière – est inhérente à la vie de tout homme.

C’est précisément pourquoi le projet des transhumanistes, et par extension, celui des Lumières scientifiques jusqu’à un certain niveau, est condamné à frapper un mur éternel, car ils « se heurtent au mystère de la vie et de la mort comme à une limite indépassable » (10).

Plus encore, il me semble que cette limite porte en elle une certaine valeur : elle est un véritable lieu où peuvent s’exprimer les hommes sensibles à la spécificité de notre humanité, défendant côte à côte les mystères de la vie et de la mort en tant que mystères. Si aucun vivant ne peut tout à fait accepter la mort, tout vivant se doit néanmoins de l’accepter. C’est là la complexité de son être.

Ainsi, à travers cette crise pandémique et tout ce qu’elle nous révèle sur nous, il nous est possible de (re)penser la place de l’expérience de la mort dans notre société : la pandémie qu’on traverse nous oblige tous à faire face – de la manière la plus frontale qui soit – à cette expérience essentielle de la limite. À notre époque Disney où un optimisme à tout prix – du moins en apparence – nous est imposé et nous écrase tous (force est d’admettre qu’il nous arrive de faire l’expérience au plus profond de nous d’une tristesse bien plus importante qu’il nous est permis d’admettre publiquement), il est alors peut-être temps de nous réapproprier un espace d’expression où on peut librement habiter nos sentiments – aussi divers et sombres qu’ils soient – de manière à éventuellement diminuer un tout petit peu notre peine à tous. Engageons-nous sur ce chemin dès aujourd’hui.

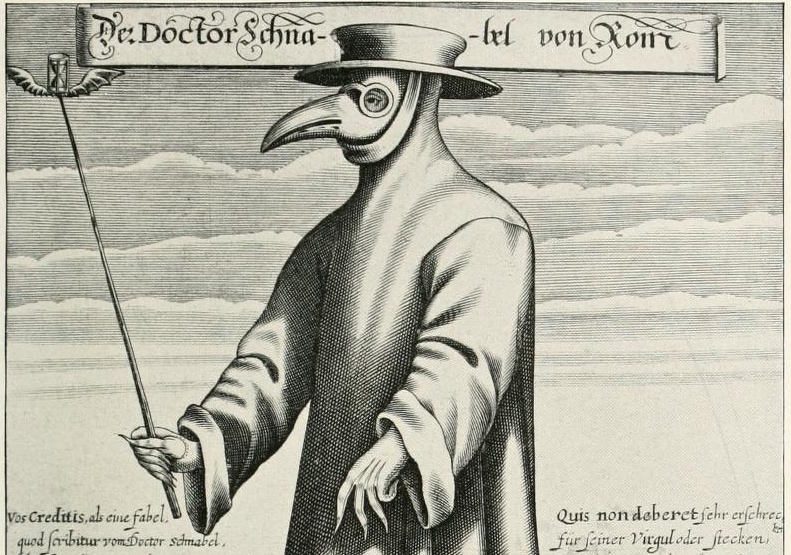

(1) Gravure de Paul Fürst (1656) représentant un médecin durant une épidémie de peste à Rome au XVIIe siècle – « Doctor Schnabel » signifie « Docteur bec » –, dans : Eugen Holländer, Die Karikatur und Satire in der Medizin : Medico-Kunsthistorische Studie von Professor Dr. Eugen Holländer, Stuttgart, Ferdinand Enke, 1921, fig. 79, p. 171.

(2) Hans-Georg Gadamer, « L’expérience de la mort » dans Philosophie de la santé, Paris, Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle et Éditions Mollat, 1998, p. 71. L’italique est de moi.

(3) Ibid

(4) Ibid., pp. 71-72. L’italique est de moi.

(5) Ibid., p. 72

(6) Isaïah Berlin, « La recherche de l’idéal », dans Le bois tordu de l’humanité : romantisme, nationalisme et totalitarisme, Paris, Albin Michel, 1992, pp. 28-29. L’italique est de moi.

(7) Kant, Idée d’une histoire universelle au point de vue cosmopolitique, 6ème proposition, Paris, Bordas, coll. Univers des lettres, 1988, p. 17.

(8) Gadamer, Op. cit., p. 74.

(9) Ibid., p. 75. L’italique est de moi.

(10) Ibid., p. 77.