Dans toute l’Europe, ce week-end du 14 mars fera date pour marquer un tournant décisif dans l’approche de la crise du coronavirus. États d’alerte, confinement des populations, interdictions de sortir, mesures de distanciation sociales sont annoncées les unes après les autres. L’Europe ferme boutique et Schengen s’écroule : l’Allemagne restaure ses frontières avec la France. Les pays se barricadent. En même temps, les chiffres de l’épidémie grimpent et amorcent une ascension exponentielle. Le quotidien Le Monde révèle une étude d’un épidémiologiste britannique prévoyant pour la seule France entre 300 000 et 500 000 morts. Certes il s’agit d’hypothèses les plus pessimistes, mais même si ces chiffres devaient être divisés par 10, voire par 20, ce serait encore beaucoup. Cette crise inédite s’abat comme un coup du destin et impose des mesures exceptionnelles ; elle pose aussi des questions dont les réponses ne sont pas toutes bonnes à entendre.

La pandémie de coronavirus pose des défis aux gouvernements, aux autorités de santé publique, aux personnels médicaux mais aussi au public, à chacun d’entre nous. Des défis en forme de questions éthiques immédiates. Sommes-nous prêts à renoncer à nos libertés pour contenir la pandémie ? Accepterons-nous de rationner des ressources médicales limitées qui pourraient sauver des vies ? Sacrifierons-nous les habituelles règles de sécurité pour accélérer la mise en œuvre de traitements et de vaccins ? Serons-nous dociles aux injonctions de distanciation sociale imposées par les autorités sanitaires et les gouvernements ?

Autant de questions— dont l’énoncé est loin d’être exhaustif — qui se posent alors que la majorité d’entre-nous n’étions pas prêts à les entendre. Serons-nous capables néanmoins d’y répondre ? Et en tirerons-nous des leçons, une fois cette crise passée ?

Sommes-nous prêts à renoncer à nos libertés pour contenir la pandémie ?

La pandémie de coronavirus percute de plein fouet la conception que nous avons de l’équilibre entre nos libertés essentielles et la nécessité de les limiter. Les peuples occidentaux démocratiques, parmi lesquels les Français font figure de pionniers, disposent d’un bien précieux : la liberté. Liberté d’aller et venir, de choisir de vivre sa vie, de décider de suivre ou non un traitement médical… Quand les télévisions et les réseaux sociaux ont diffusé les premières images de la ville chinoise de Wuhan déserte, transformée en ville fantôme, nous les avons reçues comme des bizarreries exotiques. Seul un régime comme celui de Pékin est en mesure d’enfermer sa population, sans émeutes ni rébellion.

Ce dimanche 15 mars, de nouvelles images ont été diffusées dans les réseaux sociaux : celles de la ville de Madrid, déserte, les terrasses de ses fameuses ramblas vides de tout être humain. Ce n’était pas la Chine mais l’Espagne. Ce week-end, le Premier ministre français annonçait la fermeture de tous les restaurants, bars, cafés, théâtres, cinémas… Paris et toutes les communes françaises allaient être désertées alors que le printemps pointe le bout de son nez et que chacun aspire à partager le bonheur insouciant de se prélasser sur une terrasse de bistrot.

Pour la première fois, nous subissons une mesure qui atteint subitement une de nos libertés fondamentales. Et il n’y a pas de révolution dans les rues. Tout le monde ou presque se soumet à la mesure, la comprenant comme un impératif d’intérêt général.

Pourquoi ne pas profiter d’une lecture illimitée de UP’ ? Abonnez-vous à partir de 1.90 € par semaine.

Les citoyens d’Europe en général, et de France en particulier, sont assignés à résidence chez eux. Le gouvernement les invite à ne plus sortir, à travailler si possible à domicile, à garder leurs enfants à la maison, les écoles étant fermées. Des mesures qui percutent lourdement nos façons de vivre, nos libertés de travailler, de nous éduquer, de nous rencontrer. Des mesures dont l’impact économique est incommensurable et affecte tout le monde.

Aujourd’hui, ces mesures, en France, n’ont pas encore de caractère coercitif. Les militaires ne patrouillent pas dans les rues et il n’est pas prévu d’amendes ou de mises en prison si elles ne sont pas respectées. C’est pourtant ce qui se passe ailleurs, en Chine notamment, où les contrevenants sont emmenés manu militari et risquent gros.

Si les citoyens ne respectent pas les injonctions gouvernementales, l’épidémie continuera inévitablement sa course au grand galop et le gouvernement sera contraint de mettre en œuvre des mesures plus contraignantes. Jusqu’à quel point serons-nous prêts à accepter la quarantaine à domicile ou l’isolement dans un établissement médical ? Allons-nous permettre aux autorités d’entrer dans nos maisons pour arrêter et emmener les personnes infectées ? Supporterons-nous un confinement obligatoire et total pendant deux à trois mois ?

L’urgence sanitaire va nous entraîner dans un monde inconnu où nos libertés seront compromises. Quand la crise sera passée, reviendrons-nous facilement au monde d’avant ? Les mesures d’exceptions ne seront-elles pas, au moins en partie, absorbées par la vie quotidienne et installées durablement ?

Accepterons-nous de rationner des ressources médicales limitées qui pourraient sauver des vies ?

Le grand danger de l’épidémie de coronavirus ce n’est pas tant le virus lui-même que la capacité d’absorption des malades par les établissements hospitaliers. Le COVID-19 est dans 80 % des cas une maladie relativement bénigne. En revanche, pour une portion de la population, il peut s’avérer redoutable et entraîner des soins de réanimation lourds et longs, mettant en grande tension les capacités hospitalières.

La question se posera donc assez rapidement de savoir comment répartir au mieux les ressources rares, telles que les médicaments, l’accès aux traitements de soins intensifs, les équipements de protection individuelle, le personnel et le financement de la recherche.

À mesure que le nombre de cas augmentera dans le monde, le nombre de patients gravement malades dépassera rapidement les installations disponibles, ce qui nous obligera à faire des choix difficiles.

Nous devrons décider qui est traité ou qui a accès aux médicaments ou aux technologies rares, comment et au profit de qui les professionnels de la santé et les services d’urgence seront déployés, et comment la nourriture, les vêtements de protection, les masques, les gels hydroalcooliques seront rationnés.

La tragique question du « triage » des malades en situation de catastrophe se posera inévitablement. Comment les médecins distribueront-ils des chances de survie ? En fonction de l’âge, de l’état de morbidité, de la fortune, de l’origine ? Quels seront les critères pertinents, dès lors que les critères médicaux habituels ne suffiront plus ?

- LIRE DANS UP’ : Qui vivra, qui mourra ?

Accepterons-nous de sacrifier des règles de sécurité pour accélérer la mise en œuvre de traitements et de vaccins ?

Dans l’urgence de la crise sanitaire que nous traversons, comment pourrons-nous développer de nouveaux médicaments rapidement et en toute sécurité ? La question qui se pose est relative à la recherche d’un équilibre savant entre les risques inconnus associés au développement d’un vaccin ou d’autres médicaments et la nécessité d’une réponse suffisamment rapide pour limiter la propagation du virus. Une partie de ce défi consiste à assurer une surveillance suffisante des essais cliniques alors que nous accélérons également la mise au point de nouvelles thérapies.

Pour lutter contre la désinformation et privilégier les analyses qui décryptent l’actualité, rejoignez le cercle des lecteurs abonnés de UP’

- LIRE DANS UP’ : Traitements, vaccins, tests : la recherche contre le coronavirus sur tous les fronts

Nous devrons décider s’il est approprié d’accepter des niveaux de risque plus élevés pour les participants à la recherche et les patients lorsque les enjeux sont plus importants. Il a fallu de nombreuses années pour mettre en place un cadre élaboré permettant de garantir que la recherche clinique est menée dans le respect de l’éthique. Toutefois, sous la pression de l’urgence actuelle, devrons-nous trouver des moyens de réduire la bureaucratie et la paperasserie, d’accélérer la prise de décision et de rendre le système plus réactif ?

Serons-nous dociles aux injonctions de distanciation sociale imposées par les autorités sanitaires et les gouvernements ?

Les premiers pays touchés par le coronavirus comme la Chine, la Corée du Sud, quelques pays d’Asie puis, l’Italie, ont assez rapidement choisi une stratégie de défense drastique pour arrêter la propagation de l’épidémie : emboliser complètement l’activité économique de leurs pays. Les mesures de quarantaine, de confinement, d’interdiction ont été brutales, mais la santé des populations a primé sur les lois de l’économie.

D’autres pays comme l’Allemagne, le Royaume-Uni, la France ont adopté, au début de la propagation de l’épidémie sur leurs territoires, une démarche différente. Leur stratégie consiste à ralentir la course du virus, sa propagation de personne à personne, en incitant à l’adoption de « gestes barrières » et de conduites de « distanciation sociale ». L’idée étant d’aplatir la courbe de propagation de l’épidémie pour la réduire à des proportions compatibles avec les capacités hospitalières des pays.

Cette stratégie repose sur un postulat : un comportement approprié des populations, chaque individu devenant un agent de réduction de l’épidémie s’il adopte les bonnes attitudes. Ce faisant, la stratégie évite les mesures trop douloureuses pour l’économie en laissant perdurer les activités jugées « essentielles ». Finalement, l’épidémie serait jugulée par épuisement du virus ne trouvant plus d’hôtes suffisamment bienveillants pour l’accueillir. Cette stratégie repose sur une conception rationnelle de la gestion de crise, qui ménage de délicats équilibres entre santé de la population et continuité de l’économie.

Il faut souhaiter que cette stratégie réussisse, mais elle repose sur des postulats qui posent question. Peut-on compter sur la bonne volonté de toute la population d’un pays pour qu’elle adopte les comportements conseillés par les autorités médicales ? Rien n’est moins sûr. Nombreux sont encore les français qui, malgré les interdictions formulées par le gouvernement, ont continué à se rassembler, se promener au soleil, et s’affranchir gaiement de toute mesure de prudence. Une insoutenable légèreté face aux risques, ou un esprit bravache face au destin, comparable à celui que certains adoptèrent face au terrorisme. Mais le virus n’est pas un terroriste et n’a que faire des postures de héros.

Les mesures de confinement pourraient-elles être durablement supportées ? Les spécialistes des épidémies annoncent qu’un confinement devrait durer de deux à trois mois. C’est une période longue qui se déroulera à l’orée du printemps, et rendra l’enfermement difficilement supportable. Les mesures de confinement ont un inévitable impact sur l’activité économique des personnes. Leur tolérance dépendra alors largement de l’efficacité des mesures d’accompagnement que prendra le gouvernement.

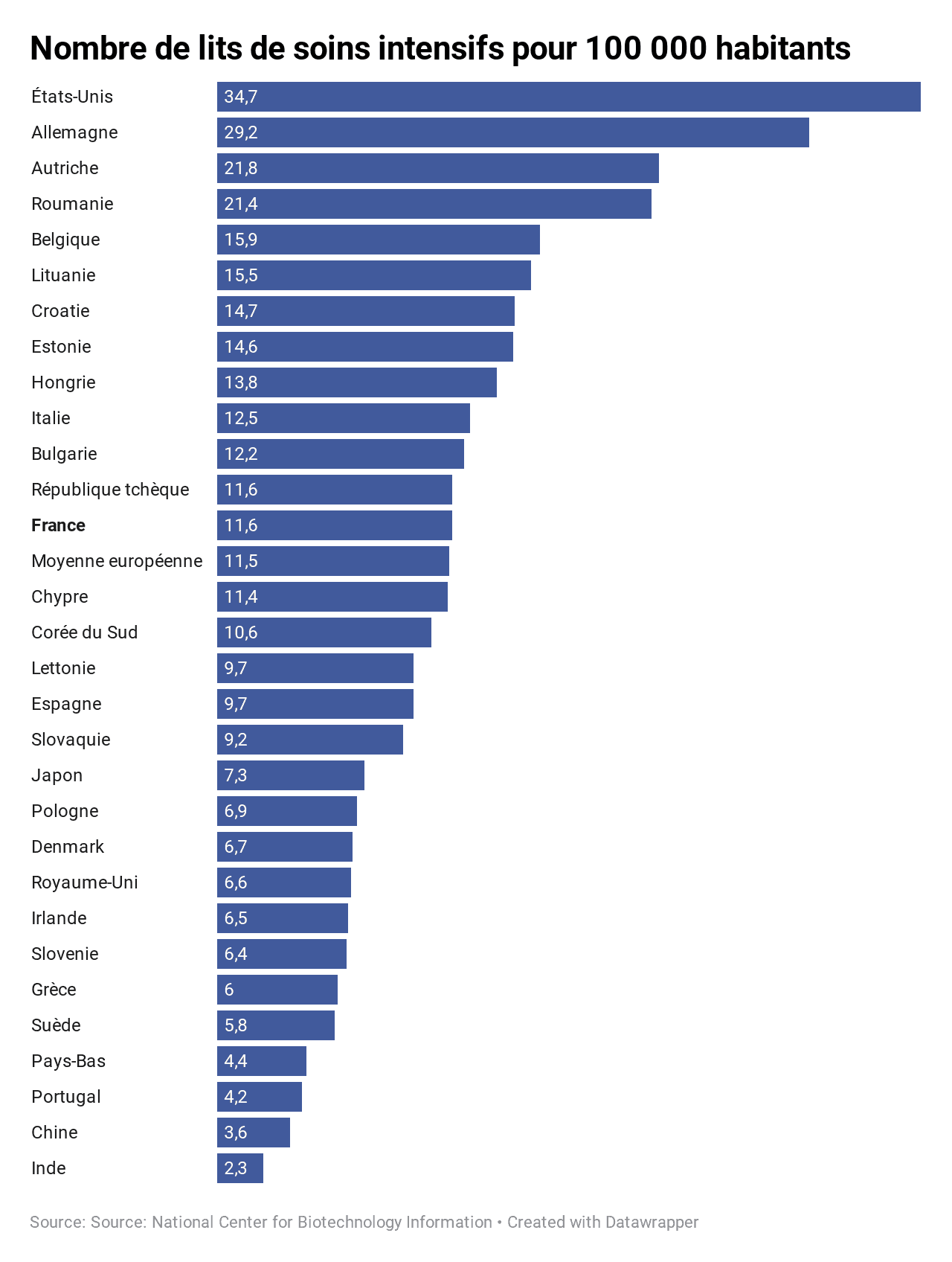

La troisième question touche, dans le cadre de cette stratégie de la « pandémie contrôlée », à la capacité des systèmes hospitaliers à amortir le choc de l’épidémie. En la matière, les pays européens déjà impactés ont des ressources très inégales. L’Allemagne est la mieux lotie avec 29.2 lits de soins intensifs pour 100 000 habitants en regard des 11.6 lits de la France et des 6.6 lits de la Grande-Bretagne.

Les chiffres prévisibles de l’épidémie annoncent 60 à 70 % de la population d’un pays comme la France ou l’Allemagne qui seraient contaminés par le coronavirus. La proportion de malades en situation de détresse respiratoire et nécessitant des soins intensifs déborde déjà largement les ressources disponibles.

La stratégie choisie de pandémie contrôlée accepte donc qu’une très grande partie de la population d’un pays soit contaminée par le virus et que plusieurs dizaines de milliers de personnes succombent à la maladie. En contrepartie, si cette expression est tolérable en l’espèce, on évite le lock down de l’activité du pays, c’est-à-dire que l’on réduit les dégâts économiques en attendant la fin de l’épidémie ou la mise au point d’un vaccin ou d’un traitement efficace. Une stratégie en forme de pari ou de course de vitesse entre la dissémination du virus et les moyens de le juguler.

Ce choix stratégique implique des questions qui ne manqueront pas de se poser au sein des populations concernées. Est-il légitime d’accepter que des millions de personnes soient infectées par le virus dans l’attente d’une éventuelle « immunité collective » ? Accepterons-nous que les personnes les plus faibles de la population (les personnes âgées ou vulnérables) soient sacrifiées comme une sorte de tribut payé au virus ? Le choix de préserver l’économie sera-t-il accepté in fine par la population quand l’heure des comptes morbides viendra ? Le journaliste italien Giuliano da Empoli rappelle que « Même la Chine, qui n’est pourtant pas connue pour ses valeurs humanistes, n’a pas osé porter à un tel point l’économisme : la colossale machine chinoise a choisi de ralentir, jusqu’à presque s’arrêter, pendant plusieurs mois, plutôt que d’infliger une pandémie à sa population. »

Autant de questions qui s’ajoutent à la pression des scientifiques sur le gouvernement, l’implorant de mettre en œuvre le plus rapidement des mesures de confinement total. Malgré toutes les questions que ce choix pose.