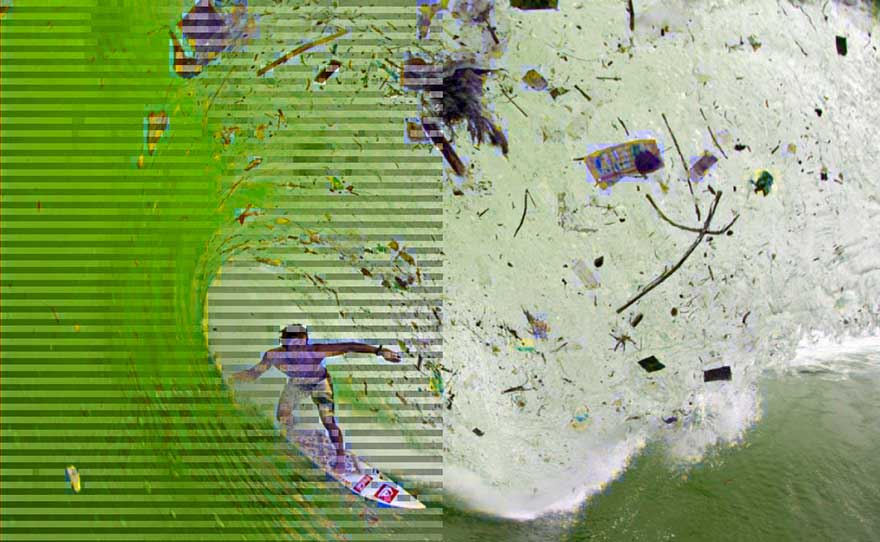

When we think of plastic pollution of the ocean, images of seabird intestines filled with lighters or corks, marine mammals choking on fishing nets, or bags drifting like a gelatinous mass immediately come to mind. Last year, one study estimated that about 8 million tonnes of plastic litter reaches the ocean each year.

Owhere and in what form this plastic ends up remains a mystery. While this pollution consists mainly of everyday objects - bottles, packaging or bags - the vast majority of debris on the high seas is much smaller: tiny particles, resulting from the degradation of plastic compounds, called "microplastics".

In a recent studywe showed that these microplastics accounted for 1 % of the total plastic debris reaching the ocean annually. To arrive at this figure - estimated between 93,000 and 236,000 tonnes - we used all measurements of the presence of microplastics and three numerical models of ocean circulation.

Genuine garbage continents

Our new estimate is 37 times higher than previous studies on microplastics. This upward revision is primarily due to a larger dataset that was consulted: we have compiled more than 11,000 measurements of microplastics collected in plankton nets since the 1970s. This database has been homogenized taking into account the different sampling conditions.

We have thus achieved that trawls operating in strong winds tended to carry much less microplastic in their nets than in calmer weather conditions. This is because winds blowing at the sea surface cause turbulence that pushes the plastics tens of metres down and out of reach of the nets. Our statistical models have taken these specificities into account.

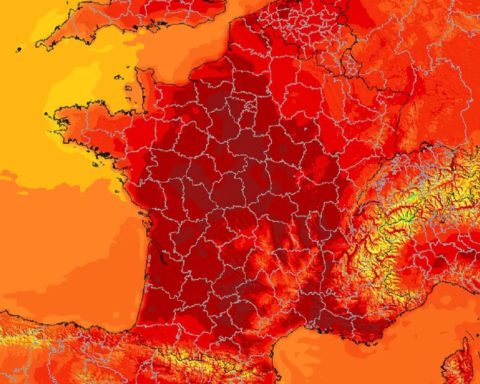

Maps of the three models used to estimate the amount of microplastics floating in the ocean (as particles in the left column and as mass in the right column). The highest concentrations are shown in red, the lowest in blue. van Sebille et al (2015)

The wide range of our results (from 93 to 236,000 tonnes) is explained by the absence of microplastic surveys over very large oceanic regions.

It is now known that the greatest concentrations of floating microplastics are found in subtropical ocean currents, also known as "gyres", where surface currents converge towards a kind of oceanographic dead end. These "trash continents" composed of microplastics have been the subject of numerous studies in the Atlantic and North Pacific. Our study includes complementary data in less studied areas, making it the most comprehensive study of microplastic debris to date.

However, very few studies have been conducted in the ocean areas of the Southern Hemisphere and outside the subtropical gyres. Small variations in oceanographic models give very mixed results in estimates of the presence of microplastics in these regions. Our study indicates where further investigations should be carried out to refine these assessments.

A small part of plastic pollution

The floating microplastics that are collected in plankton nets are among the best quantified plastic debris, in part because they have been collected by researchers studying plankton for several decades now. But these microplastics represent only a small part of all the plastic polluting the ocean.

After all, "plastic" is an umbrella term for a variety of polymers with many different properties, including density. Some very common plastics are denser than seawater and sink as soon as they enter the ocean. However, it is well known that it is not easy to estimate the quantity of plastics present on the seabed, especially in coastal areas, not to mention the immense ocean basins with an average depth of 3.5 kilometres.

It is also not known how much of the 8 million tonnes of plastic waste that pollute the marine ecosystem each year ends up on beaches. In a one-day clean-up campaign in 2014, volunteers from theInternational Coastal Cleanup collected no less than 5,500 tonnes of waste, including 2 million cigarette butts and hundreds of thousands of food wrappings, bottles, corks, straws and plastic bags.

We know that this plastic waste will eventually disintegrate into micro-particles. But how long it will take for large pieces - such as buoys or fishing gear, for example - to break up into tiny pieces of debris when exposed to sunlight is still largely unknown. How small these pieces could be reduced to before being degraded by marine micro-organisms is even less certain - largely because it is very difficult to know whether the microscopic particles in question are actually plastic.

Laboratory and field experiments to expose plastics to the elements should provide a better understanding of the fate of different plastics in the ocean.

Act Now

Since we know that a huge amount of plastic ends up in the ocean every year, what good does it do us to know whether it is a cork found on a beach, a lobster trap lost on the seabed, or an almost invisible particle floating offshore? If this pollution was merely cosmetic, it would not matter to us much indeed.

A Steller sea lion observed in Vancouver, Canada, with a deep neck wound. Wendy Szaniszio

But this ocean pollution poses a threat to many marine species; and this risk varies according to the amount and type (size, shape) of debris to which an animal is exposed.

For a curious seal, a drifting packing slip presents a serious risk of strangulation; as for microplastics, they could just as easily be absorbed by gigantic whales as by microplankton. Until we know where the thousands of tonnes of plastic in the ocean are, we cannot fully understand the effects on marine ecosystems.

But we don't need any further research to try to stop this serious problem. We know that it is not possible to clean up the water from the hundreds of tonnes of microplastics that spread over thousands of kilometres on the surface. Instead, we need to close the sluice gates to prevent this waste from reaching the ocean in the first place.

In the short term, systems must be put in place to collect and recycle this waste where it exists. most needThis is the case in countries with strong economic development such as China, Indonesia and the Philippines; here, strong economic growth is accompanied by an increase in waste that is too rapid to be treated by the existing infrastructure. In the longer term, we need to rethink our use of plastics in terms of their use and life cycle. At the end of the day, plastics should be seen as a resource to be processed and used, rather than simply as a disposable product.

Kara Lavender LawResearch Professor of Oceanography, Sea Education Association

Erik van SebilleLecturer in Oceanography and Climate Change, Imperial College London

Photo: Zak Noyle / Aframe

The original text of this article was published on The Conversation.