57% of city dwellers aspire to live elsewhere. The surprise is less in the tendency to want to leave the city, the big one, than in the intensity of the demand and the reasons for it. The dilemma, according to an ObSoCo study, is not to choose where to go, but to know how to build, through one's own practices, an "elsewhere": in France and in Europe, people have told about the city as they live it, the one they dream of and the ones they reinvent through new uses. Work, consumption, mobility, housing, relationships with others, citizenship, so many areas to explore in order to build the city of tomorrow.

L’Observatory of Emerging Uses of the City was carried out by the ObSoCoin partnership with Chronos. Bruno Marzloff deciphers urban lifestyles in France and Europe and looks at the new practices that are redesigning the city.

What is expected of the city: is it natural, collaborative? short distances? connected? diffuse? self-sufficient? A bit of all of this, certainly, but not in the way that the providers think.

Once we listen to the expectations and representations of the city's users, it is difficult to draw an ideal city, as these are so fragmented and paradoxical, and as the nuisances associated with the city clash with the experience of a desirable urban experience. The challenge then lies in the ability to free up other uses of the city, allowing it to be reinvented.

It is in order to deepen the nature of these uses that ObSoCo and Chronos have joined forces to launch, with the support of ADEME (French Environment and Energy Management Agency), CGET (General Commission for Territorial Equality), Clear Channel and Vedecom (Institute for Decarbonated and Communicating Vehicles and their Mobility), the first Observatory of Emerging Urban Uses.

This observatory is based on an extensive online survey of a representative sample of the French population aged 18 to 70 years old of more than 4,000 people, questioned from 3 to 31 July 2017. In order to establish international comparisons (limited to the European level for this first edition), the survey was conducted in parallel in Germany, Italy and the United Kingdom, each with a sample of 1000 people representative of the national population. It shows the evolution of the representations of the city within the populations of the territory, the development of new forms of aspirations in terms of living space and the emergence of other practices in terms of mobility, consumption, but also sociability and exchanges.

A need for a balanced city

Three entrances articulate and sketch a framework, a perspective and a narrative. Around it is organized a galaxy of observations.

1. The dilemma: How do the French (but this is true in the other three countries visited) love and reject the city at the same time? "I love you, neither do I. » The bigger it is, the more it welcomes hyperactivity, the more it motivates rejection.

2. Invention: How do users practice the city, invent it?

Through the invention of new behaviours, we can speak of a "balanced city". Weighted by them, that is to say, since the town planner and the private and public actors are in a different story from that of the users.

3. Balances: How do users conceive of the city and represent it to themselves? Rejecting excesses, they formulate other balances, utopias.

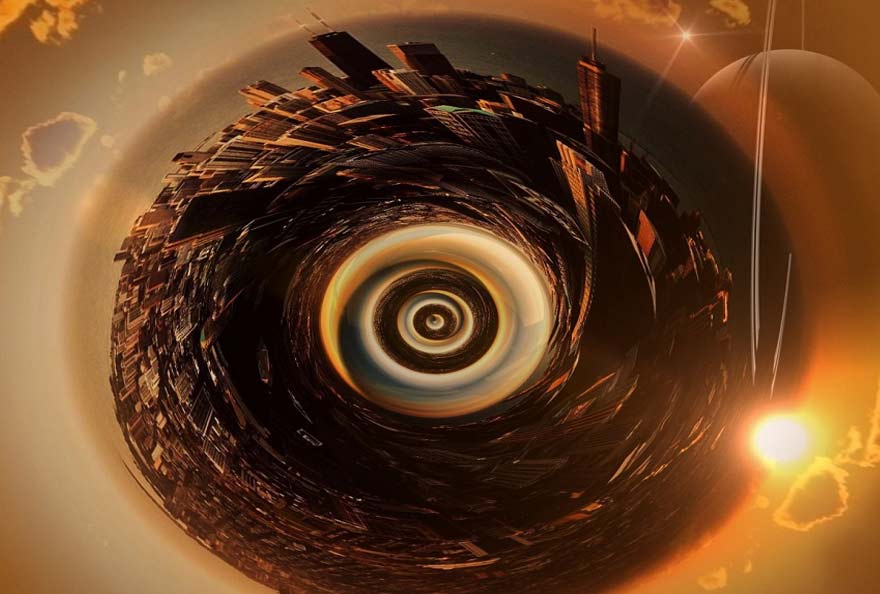

Hypothesis: A centripetal and devouring metropolitan dynamic (let's call it a "vortex") perpetuates the attraction of the hypercentres of the metropolises competing at the global level. It consolidates a Fordist logic that has been at work in functional urban planning for a century. This city ignores demand and is in fact lagging behind the new uses that are shaping it.

1 - The dilemma

A shadow hovers over the city. Its future is not necessarily bright (9% "tomorrow will be better" vs. 47% "tomorrow will be worse"). This translates into a neglect and at least strong objections on the city, at least the big one. The measure of urban malaise is immediately grasping. How can it be explained that one French person in two (48%) aspires to another residence, somewhere else?

With a powerful overweight in IDF (62%) and in large cities, but still 1/4 of the residents of isolated municipalities. To put it another way, the desire for escape correlates with the size of the city. How can we explain that these unsatisfied people do not succeed in their quest? Is it so difficult to move? Or is the very object from elsewhere unreachable? Would this elsewhere be a utopia?

In fact the plausible explanation for this figure - even stronger in Italy and the UK than in France - is twofold. On the one hand, city dwellers have little choice but to stay where they live, because the grass is definitely not greener elsewhere, and the nets that hold the city dweller back are too strong. For the city offers itself with its ambivalent effervescence - culture in all its dimensions (cultural diversity, 1st item of representation of the city, 7.0 points), multiple sociabilities, income, wealth of resources, festivities, entertainment ... ; on the other hand, one has to accept the lack of time, the invading car, noise, pollution, congestion, fatigue, stress, high prices, lost time ...

The city has a dark side that cannot be dissociated from its undeniable advantages. It is this trap that Europeans denounce in this aspiration to live elsewhere. To live elsewhere is to find this same cocktail; since it is not the actors who make the city, it is its size that determines it. Is this headlong rush towards hyperurbanisation of the city fatal?

2 - The invention

Hence the second part of the dialectic. Indeed, the complainant expresses his dismay, but does not give up facing his contradiction. So he does not leave the city, but tries to transform it from within. To escape the trap of immobility from above is to invent uses for the city (Michel de Certeau, The invention of the everyday life), but also in shaping the skills needed to use them. In a way, it means rebuilding the city on the city, not through infrastructure but through behaviour, and therefore through the services that are in demand.

Without claiming to exhaust the subject, let us highlight a few major chapters of innovations in use in the city.

1/ Mobility and agility :

The French - sometimes to a different extent in one direction or the other than Europeans - are inventing a great deal in terms of mobility (self-service bicycles, walking, carpooling, short car-sharing, car-sharing, VTC, etc.), they are in favour of multimodality, they bypass teleworking, third places, remote control, they value proximity and neighbourhoods, etc. They are also developing the use of the Internet, the Internet and the Internet.

2/ This variety of practices, agility and resilience with local shops is found in the tradeThe main reasons for this are the lack of a clear understanding of the role of the Internet, AMAPs, e-commerce and the variety of delivery methods. Proximity again! 63% are potential users of neighbourhood service kiosks.

The sense of belonging is built at the local level. 86% feel at home in their neighbourhood and another 85% at the neighbourhood level.

3/ Collaborative practices are first and foremost a response to an expensive city, but they are proving to be virtuous and ecological; the French confirm that they want to accentuate their already significant recycling practices.

4/ Ecology is absent from the city (4.5 points). It is returning to it through the plebiscite of self-production in food and soon in the energy field (61% of the owners are ready to adopt self-production in energy).

5/ Proximity and resilience with fab labs. Who make you dream if you are not already there (3% of users only). The future also claims to be creative, with the consent of 44% to fablabs to reproduce objects identified online, or 56% to repair used household equipment in fablabs.

6/ Health, well-being, vitality. 45% are expecting street furniture dedicated to sports, health and well-being, more than travel information kiosks, which are in any case made obsolete by mobiles and their applications.

7/ Openness to the world and citizen involvement. 63% are in favour of the coexistence of a diversity of cultures. 64% of the French would like to see the development of a participatory budget in their commune.

This is a largely incomplete but tangible and robust catalogue of urban creativity.

3 - The new balances

If the ideal city does not exist because of the contradictions of the Fordist city pushed ever further, higher, denser, more agitated, the respondents suggest denouncing the excesses and changing the way we look at it by combining these variables that make up the city and urbanity, following the example of the city of Delphi, which displayed on the portico marking its entrance: "Nothing too much". Rejecting the Fordist city's headlong rush, the respondents' point of view leads to the formulation of a theory of equilibrium.

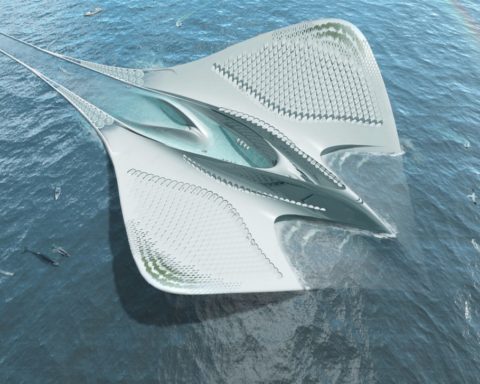

- None of the six city models proposed in the survey (natural, diffuse, short distance, collaborative, self-sufficient, connected) is enthused; connected and diffuse cities are even less so than the others. The solution is a weighted city, made of a brick layout, compromised between the six entrances to the ideal city.

- The city is also the choice of a city size and a location within the metropolitan grid. The model will then be the medium-sized city or the small town close to the big city, or the model of the village within the city. Another way of redoing the city on the city.

So this balanced city formulates, sheltered from "too much", the quest for human size, good living, what is humanly manageable, or the city at hand.

- Neither too big nor too small, we repeat over and over again in the verbatim.

- Not too close to the big city, ... not too far.

- The living space - that is to say, the living area also a territory of resources and amenities - is halfway between the city of short distances and the diffuse city.

This balanced and frugal city is a combination of multiple binomials in which urbanity is recomposed:

- Between the mineral and the green space, one must not choose, one must compose intelligently, and avoid the artificial, the superficial.

- A city should be dense enough but not too vertical.

- We reject the connected or futuristic city, but we do not reject data services that bring fluidity to a complex daily life.

- This town probably still has a few cars but no congestion.

- It is collaborative but not coercive.

Between the resource city and the city within reach and the city wellbeing, the exercise is as difficult as reconciling the active city and the inclusive city. To sum up, a city that is neither too concentrated flirting with confinement, nor too dispersed at the risk of loss of contact and urbanity, but also at the risk of mobility: too much particular mobility has hurt the city, leading its inhabitants to look for a way out. These hybridizations reflected in the sample's responses and verbatim comments can be read as the quest for calm and balance of an urban dweller who aspires to a quality of life without losing the advantages of an accessible city. This is not a non-choice, but rather reveals its very great difficulty.

4 - Delay and imbalance in supply, the "winner-take-all city"

This analysis underlines the extent to which the hyperactive city that concentrates the effervescence, which makes "noise", "pollution" and "congestion" its major and obvious symptoms, meets so many objections. Clearly, the construction of urban supply is lagging far behind demand expectations.

Why? Beyond the inertia of Fordist models, the abusive place of the car, zoning and its after-effects, economists and town planners put forward an intriguing explanation.

In the competition between cities, the "winner-take-all urbanism." is the monopolisation of value by certain cities and players capturing and concentrating the creative economic apparatus, innovation and economic growth on their territory in an exponential movement, identical to that of companies whose value and performance feed off their growing power, wiping out the rest of the market.

Their driving force is to make themselves indispensable - we hate Facebook, but we can't do without it. The same goes for the city, which we can't stand, but which we won't leave either, so vital are its resources. Its conclusion is a form of "vortex" that sucks in the living forces and throws its margins back into its steps, opening up another path for excesses.

A city governed by the duality of the tropisms that shape its territory: those of natural origin and those of human origin. Always too much "too much"; precisely the ubris that the ancient Greeks condemned.