"Nothing will be the same as it was before." This sentence has been resonating on the web for several weeks now. With containment, a tidal wave of questions about tomorrow's world is flooding onto our screens. And the future of work occupies a central place in this questioning (e.g., how will the work of the future be perceived and how will it be perceived? here and there). In fact, this "nothing will ever be the same again" is not so much a question as an affirmation. An affirmation in which one perceives both a deep unease and the desire for a slightly better future. What if we could build another future of work, thanks to the commons?

A "work system" too vulnerable

Let's move on from the absurdity of debates such as " Will we still be kissing at the office tomorrow? "(to which the guest expert on the TV set obviously replies "Ewell no, nothing will be the same anymore... ")What is at stake here is the vulnerability of the "work system" as a whole.

First of all.., vulnerability of our division of labourThe fragmentation of supply chains and the widespread interdependence of activities make work dependent on distant shocks. When the system gets a flu, all workers suffer, while in a globalized economic system.a less interconnected system would be more resilient... at the local level.

Next, vulnerability of the ecosystem in which human activities take placeThe danger of the virus is a stinging reminder of the climate emergency: in the Earth system, the fruits of human labor depend on the non-human world. The model of work organization inherited from the past has as a corollary the domination of nature and the extensive exploitation of energy resources. What will be the corollary of the future?

Last but not least, precariousness of a growing share of workers Health, food production and distribution, maintenance of infrastructure... What about a world where the people who care for the community are less well paid for their workwhile putting further endanger their health than the others?

This "nothing will be the same again" sounds like a "nothing". must no longer And if we don't start transforming the way we organise our work, in the face of the repeated crises that climate change will bring, we will have to be content with "nothing has changed" (which goes very well with the bitterness of a little "it was better before").

What is the future of work to meet the climate challenge?

We therefore need a more resilient and reasoned system. A world where work serves to repair and care for the world rather than to exploit and dominate it. Where economic and financial flows reconnect with the reality of territories and ecosystems. And whatever the future may bring, labour organisations (companies, associations, cooperatives, administrations, etc.) will have played a central role. Either because of the inertia of the business as usualor through a profound transformation of their own relationship to work.

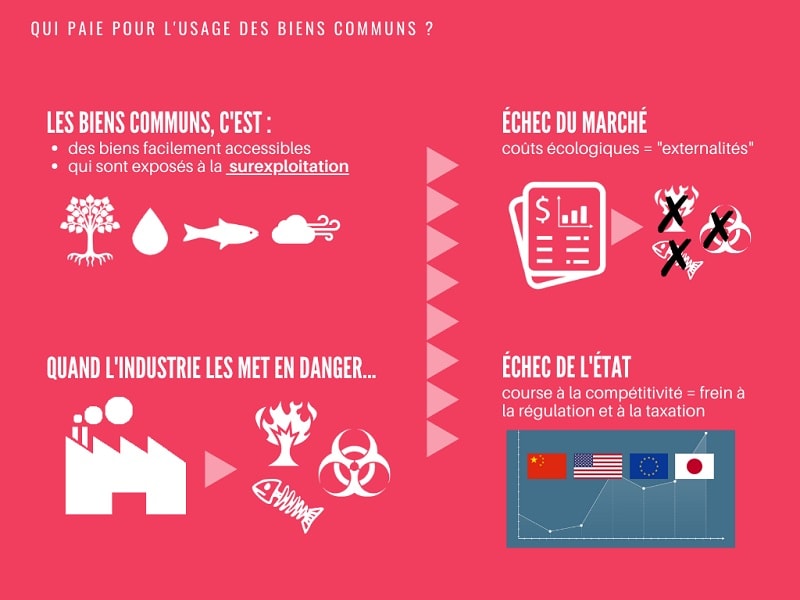

But where to start? The Godwin point of any discussion on the transformation of the world is the "state versus market" debate. On the one hand, the authority of the state, which can impose new rules of the game, and on the other, the mechanisms of the market and free competition, which could provide innovative solutions. The problem with this eternal debate between socialism and liberalism is that it too often remains trapped in a productivist and abstract perspective. Whereas another path is already open to the world of work: that of the commons.

The protection of common property, a new raison d'être of the work?

If your work helped protect the planet, would it make more sense to you? The commons are the subject of research that earned Elinor Ostrom the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009.

What is common property?

Two characteristics distinguish them from other types of goods: (1) they are difficult to deny access (the so-called "stowaway problem"), and (2) they are at risk of overexploitation as limited resources.

Ostrom's genius was to open a third way in the debate between the advocates of public management of common goods by an all-powerful state and the defenders of the market and private property as the best way to regulate the use of a resource: local and collective governance.

Key success factors

In addition, by studying various examples of communes such as forests or water reserves in America, Asia, Africa and Europe, Ostrom identifies the key factors for the success of the governance of communes, the first of which is the existence of a community of individuals committed to participating in this governance. It is this participation in the community that creates the mutual obligation necessary to respect the rules defined by the collective: rules of use, conflict arbitration, application of sanctions, etc. This represents a great deal of work.

For finally, who will deny that this active participation of individuals in the governance of common goods deserves the name work in the noblest sense of the word? It is not a question here of saying that participation in the governance of common goods should replace the wage-earning model thanks to a universal income. But it is a question of envisaging this eventuality: what if we gave ourselves the means (time) to work for the protection of common goods?

The Common as the future of work organisation

You may have noted that the key success factors identified by Ostrom are also organizational principles. These principles are found at the margins of the world of work: in hackers and in free software, in third places and in some "horizontal" companies. Beyond common goods, there is therefore a principle OF THE COMMON that suggests other possible ways of organizing work.

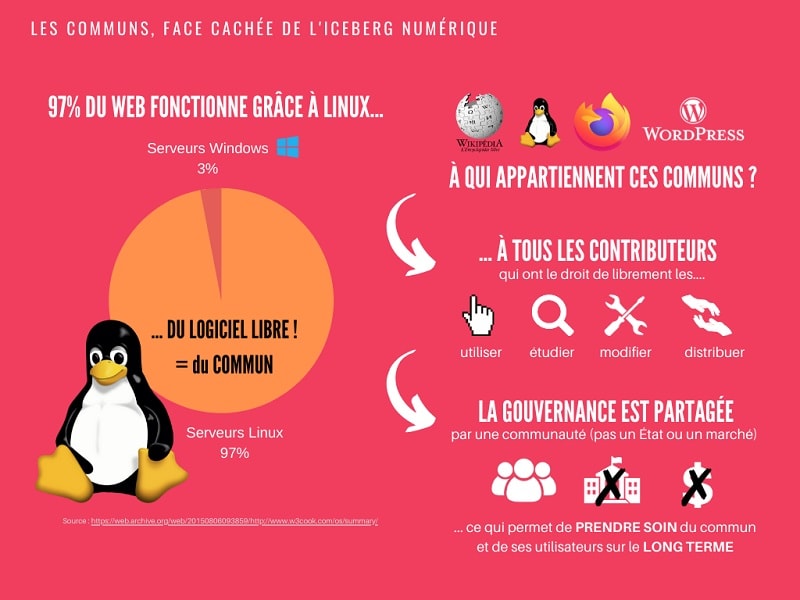

Web and common, for another future of work

Let's start with the digital. In case you didn't know it, almost all of the Web is powered by operating systems. LinuxWithout this monument of free software, our experience of the web would be reduced to nothing, compared to the possibilities it offers us today. The largest encyclopedia in history? Wikipediawhose code is free and whose contents are under licence. Creative Commons. WordPress, which we use to create blogs? Also under a free license, and it allows us to manage a third of the world's websites. All these projects under a free license ("Copyleft") are Digital Commons. Anyone is allowed to use, study, modify and distribute them as long as they do not deny these same rights to their own users.

And guess what? A huge part of the work needed to build these commons is completely outside the boxes of the working world we know. Their contributors are often volunteers. They live on different continents. They are not subordinate to the authority of a boss. It is not the lure of gain that leads them to contribute, but an ethic of freedom and equality (does that remind you of anything?), often with a strong commitment to theempowerment of users and the protection of privacy.

Territories and commons, for another future of work

Second, third places. Fablabs, coworking areas rural, medialabs, recycleries, repair cafes are all alternative ways of organizing work on a territory.

Community members are often freelancers, freelancers, VSEs, volunteers and increasingly employees. The legal vehicle of the third party, when it has one, is the association, the cooperative, even the local authority or even the traditional public limited company.

But what is striking is that the principles of third place governance (collective rule-making) are exactly the same as those identified by Elinor Ostrom in her work on common goods.

Enterprise and common, for another future of work

Finally, the company. First of all, it should be remembered that the company itself has no legal existence, unlike a corporation (public limited company, cooperative, etc.). A public limited company owns its assets. But what about work organisation? Corporate culture? Relations between employees? Managerial rules? liberated companies, holacracies, sociocracies, Teal organizations and other empowering organizations are attempting to acknowledge the inappropriateness of the enterprise to implement shared governance of the work organization itself. If the company is privately owned, thecompany as a collective project and as an organization can be a matter of common interest. However, it should be noted that the SCOP model (and other cooperatives) seems more promising than that of liberated companies. Why? Because the principle of shared governance is then written into the very DNA of the company (its legal status and economic structure). With the capital structure of the traditional public limited company, the risk increases that collective governance will be subordinated to the sole imperative of profit.

Conclusion

Work plays a hyperstructuring role in our model of society. Our current organization of work is both a driving force of modernity and one of the causes of our vulnerability. The opportunity we have is that this vulnerability can serve as a trigger to find the human momentum that will help us overcome this dilemma. The commons offer us a potential way out. Both a vital infrastructure of our world and "acting together", they help us to build healthier productive ecosystems. To paraphrase two emblematic authors of the commons' thinking, "... the commons are the only way out of our world. the common is the inappropriate " (1).

The commons can help us to build another future of work, but there is still a lot to be done. Whatever your profession and level of qualification, there is no shortage of building sites to organise a real transition into the world of work.

Gregoire Epitalon, Co-founder of libertalia.work

(1) « The common is the inappropriate... ", by Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval - " Common, Essay on the Revolution in the 21st Century "Edition La Découverte, 2014

To go further :

- Release of the N°1 of the quarterly review TaF, Working on the future, directed by Patrick Le Hyaric