On December 12 and 13, a meeting is being held in Paris on December 12 and 13. health symposium. Organized by the Centre d'études des techniques, des connaissances et des pratiques (CETCOPRA), this meeting will question the stakes of self-monitoring generalized by sensors, early diagnosis, permanent self-quantification. Two organizers will present the landscape of "assisted health" and point out some questions: what figures of the body, the living and health shape these practices? What is their impact on current medicine and public health policies?

Healthism" is an ideology that increasingly pervades our contemporary societies. This doctrine makes the permanent improvement of one's health a moral imperative. Its origin probably dates back to 1946, when the World Health Organization in its Constitution defines health as "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity". In the post-war enthusiasm, the goal of raising the level of health of populations to the highest level was clearly a social and egalitarian one.

Thirty years later, the situation has radically changed. The battle against disease and aging as well as the optimization of well-being have become the watchwords of a new market. It is no coincidence that people are starting to talk about healthism in the United States, the western country with the most privatized health care system in the world. Robert Crawford, a public health analyst, was the first to formulate the concept of healthism in 1980 to criticize the commercialization and individualization of health. This trend has increased dramatically with the technological and scientific innovation that has revolutionized contemporary biomedicine.

Quantified or standardized "healthy living"?

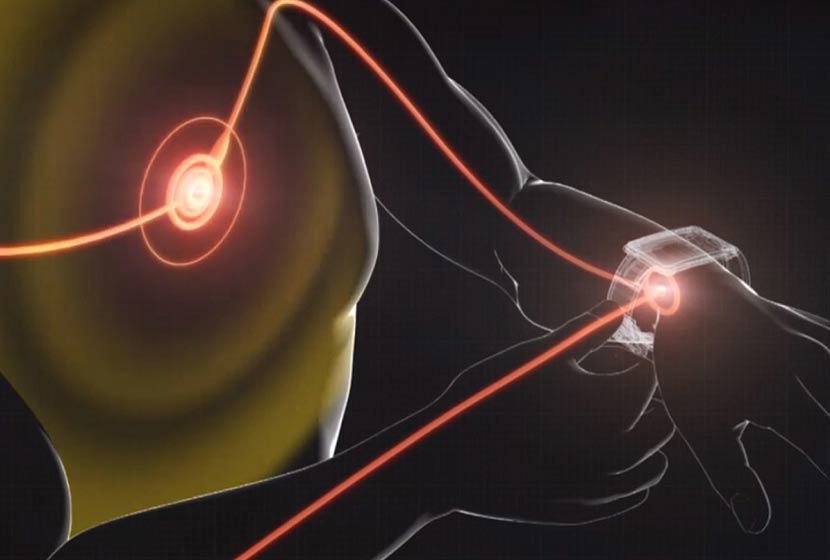

Examples include pedometers, biosensors and measuring devices used to generate personal biological data about diet, health, sports or sexual performance. All of these technologies are part of the "self-quantification" (quantified self) which consists in making one's own body a clinical object under constant observation, even in the absence of disease. The offer is vast. There are a multitude of biosensors connected to the smartphones with applications that push you to drive the most miles, burn the most calories, or share performance and compare it with friends and other users. Another popular example is "diet" applications, which can determine the ideal weight and indicate how to reach it, taking into account the user's diet. All these forms of "self-tracking" reduce the notion of well-being, like the human body, to a simple matter of numbers, an algorithmic "numbering" of oneself. We train and eat for the sole purpose of producing data to ensure a level of good health. If the fetishism of data is reminiscent of the "surveillance society" described by Gilles Deleuzethe scenario becomes even darker when you think about the possibility of sequencing his DNA.

Examples include pedometers, biosensors and measuring devices used to generate personal biological data about diet, health, sports or sexual performance. All of these technologies are part of the "self-quantification" (quantified self) which consists in making one's own body a clinical object under constant observation, even in the absence of disease. The offer is vast. There are a multitude of biosensors connected to the smartphones with applications that push you to drive the most miles, burn the most calories, or share performance and compare it with friends and other users. Another popular example is "diet" applications, which can determine the ideal weight and indicate how to reach it, taking into account the user's diet. All these forms of "self-tracking" reduce the notion of well-being, like the human body, to a simple matter of numbers, an algorithmic "numbering" of oneself. We train and eat for the sole purpose of producing data to ensure a level of good health. If the fetishism of data is reminiscent of the "surveillance society" described by Gilles Deleuzethe scenario becomes even darker when you think about the possibility of sequencing his DNA.

In addition, hundreds of thousands, if not millions of pieces of genetic data can be accessed through open-access genetic testing services on the Internet. The data, known as SNPs (from the soft name of single-nucleotide polymorphismThe information provided on the website (e.g., single nucleotide polymorphism) is capable of informing the user about the presence of rare diseases, the predisposition to common diseases (ranging from cancer to obesity), physical traits (such as blue eyes or breast size), or ethnic origins. The company 23andMe has become a world leader in DNA decoding by promoting the sharing of data on a dedicated social network that allows Internet users to learn about predisposition to a disease (such as Parkinson's disease), or more simply about the genetic traits that determine eye colour. Medical communities, especially in Europe, denounce these services as devices aimed at commercializing developments in genomics without providing any clinical utility. Indeed, it is not easy for ordinary people to understand the meaning of an extraordinary amount of extremely complex data.

Useful service, as long as the person can make sense of it.

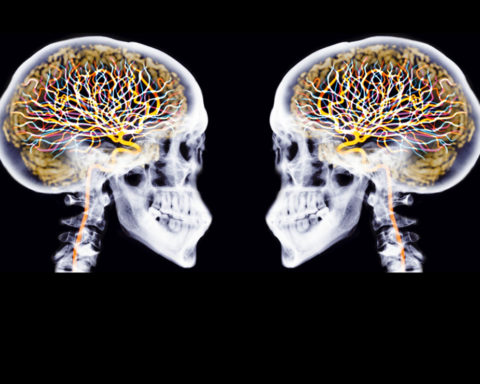

One may wonder to what extent healthism contributes to the popularization of biomedical knowledge, or even to the advent of new modes of knowledge. The case of Vivienne Ming is often cited. This scientist had no expertise on diabetes before her son was diagnosed. She later developed a system capable of measuring glucose levels continuously, taking into account her child's diet and activity according to the dose of insulin injected. Contrary to her expectations, Vivienne Ming realized that the rise in her son's blood sugar level was not related to his diet but rather to his stress level. In the case of "mainstream genomics", this is a more collective approach, inspired by the utopias of free software. Biologist Greg Lennon and computer scientist Michael Cariaso have thus jointly developed an online encyclopaedia, "SNPpedia", which provides Internet users with interpretations of their genetic data. They can also contribute to improving this interface thanks to a method of open source. What kind of knowledge is built through these direct links between patients and these technomedical innovations?

In the case of "mainstream genomics", this is a more collective approach, inspired by the utopias of free software. Biologist Greg Lennon and computer scientist Michael Cariaso have thus jointly developed an online encyclopaedia, "SNPpedia", which provides Internet users with interpretations of their genetic data. They can also contribute to improving this interface thanks to a method of open source. What kind of knowledge is built through these direct links between patients and these technomedical innovations?

The personalization of the individual through data therefore represents today one of the strong trends in the biomedicalization of technologically advanced societies. In this context, the patient, just like the healthy individual concerned about his or her well-being, "produces" and "consumes" digital data which, correctly correlated and interpreted, enables practitioners to make a decision on his or her state of health. This is the case in the field of telemedicine today, particularly in France.

Telemedicine and digitization of humans: the threat of infobesity

The "digitization of oneself" by means of biosensors and "communicating medical devices" (CMDs), particularly in the context of telemonitoring, makes it possible to capture vital patient data (pulse, temperature, weight) and to anonymize them before they are analyzed according to criteria such as age group, sex and pathology. Therapeutic protocols are then drawn up on the basis of this "patient information" which is re-evaluated using averaged data. The knowledge of the body is therefore carried out, in a telemedical context, according to a generically customizable model. And this personalisation by data, data and even by Big Data (positioning of the patient in relation to averaged data) modifies, among other things, the global perception of the disease, which becomes an object of quantification, relativised, even objectified. This view has always been more or less present in medicine, but what is new here is the acceleration in the transfer and dissemination of these data. And behind this acceleration is the threat of infobesity and over-diagnosis. In this way, the digitalization of the body, which has led to the emergence of the digital patient, or patient 2.0, is accompanied, in a telemedical context, by the patient's appropriation of connected objects (smartphones, tablets, PDAs) and mobile applications.

The "digitization of oneself" by means of biosensors and "communicating medical devices" (CMDs), particularly in the context of telemonitoring, makes it possible to capture vital patient data (pulse, temperature, weight) and to anonymize them before they are analyzed according to criteria such as age group, sex and pathology. Therapeutic protocols are then drawn up on the basis of this "patient information" which is re-evaluated using averaged data. The knowledge of the body is therefore carried out, in a telemedical context, according to a generically customizable model. And this personalisation by data, data and even by Big Data (positioning of the patient in relation to averaged data) modifies, among other things, the global perception of the disease, which becomes an object of quantification, relativised, even objectified. This view has always been more or less present in medicine, but what is new here is the acceleration in the transfer and dissemination of these data. And behind this acceleration is the threat of infobesity and over-diagnosis. In this way, the digitalization of the body, which has led to the emergence of the digital patient, or patient 2.0, is accompanied, in a telemedical context, by the patient's appropriation of connected objects (smartphones, tablets, PDAs) and mobile applications.

By participating in the therapeutic protocol through these devices, the patient acquires knowledge about himself that he can share with his family or social caregivers or health professionals. This acquisition and sharing of "patient knowledge" has three main consequences. On the one hand, the patient becomes a "consumer" of data concerning his or her own state of health. On the other hand, he enters into a relationship of co-construction of knowledge with the different partners involved in his therapeutic protocol. Finally, he can "individuate" his own health standard thanks to the empowerment acquired by the connected objects (e-balance, connected blood pressure monitor, computerised pacemaker). These give him the possibility to "follow" and therefore to better understand the evolution of his disease. Connected objects and mobile applications are therefore new self-care techniques that bring the patient into the era of technological "self-care".

Self-surveillance or massive packaging?

Connected objects and applications certainly represent progress for the individual because they make it possible to prevent certain crises in chronic patients, to anticipate states of suffering and to prepare for certain treatments. They have an ethical value in that they aim at the noble goal of a "good life", which includes the general improvement of health. However, it is noticeable that through the use of these objects the patient seems less "empowered" than "responsible". He seems to be less the actor of a transformation of himself by himself than the agent of a delegation, i.e. of a "self-surveillance" based on algorithmically determined selfcare techniques, which seem to enhance an essentially quantitative vision of the body.

Connected objects and applications certainly represent progress for the individual because they make it possible to prevent certain crises in chronic patients, to anticipate states of suffering and to prepare for certain treatments. They have an ethical value in that they aim at the noble goal of a "good life", which includes the general improvement of health. However, it is noticeable that through the use of these objects the patient seems less "empowered" than "responsible". He seems to be less the actor of a transformation of himself by himself than the agent of a delegation, i.e. of a "self-surveillance" based on algorithmically determined selfcare techniques, which seem to enhance an essentially quantitative vision of the body.

Within the tele-patient's universe of "informational prosommation" (producer and consumer of data), digital knowledge about oneself nevertheless confers a certain degree of empowerment, which stems from the patient's ability to self-manage, or even self-regulate, according to the data acquired and shared about his or her illness on the telemonitoring platform. The question of the "technologically assisted" patient and that of "self-care" can therefore no longer be locked between a sterile alternative between total freedom of autonomy or, on the contrary, medical guardianship.

But, then, what is healthism? What is self-care in the age of new technologies? Is it an evolution towards a society that makes health a consumer good reserved for the wealthiest social classes, or is it an involvement of all in medical innovation? This conference invites us to adopt both an open attitude and a critical look.

Philippe Bardy, Ph.D. student in philosophy of emerging health technologies

Mauro TurriniMarie Curie researcher, at CETCOPRA University Paris 1- Panthéon-Sorbonne