While "free models" are nothing new, the digital economy has given them an unprecedented scale. From the LinkedIn professional network to dating applications and video games, digital players are deploying a range of strategies in which the user has free access to a partial service according to a logic of "free of charge". freemium. In some cases, the user is never even involved, with a "third party activity" (such as licensing) or "third party financing" (such as advertising) providing the service publisher's revenues. It may come as a surprise to some that free of charge - so widespread in the digital world - may become an issue that is prompting more and more competition authorities to open investigations against the digital giants, led by GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft), including in the United States where they come from. Because, ultimatelyHow could a seemingly free service be detrimental to consumers and, beyond that, to the general interest?

Natural Concentration

Already, some market practices based on the exploitation of personal data are questioning. The scandal Cambridge Analytica For example, the 2018 revelation of the fraudulent use of Facebook data for political influence put the spotlight on the commercial, and covert, exploitation that can be made of personal data. And the suspicions about Google's practicesThe European Commission and the European Commission, suspected of circumventing the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe, recall that legal protection measures remain in place. generally ineffective.

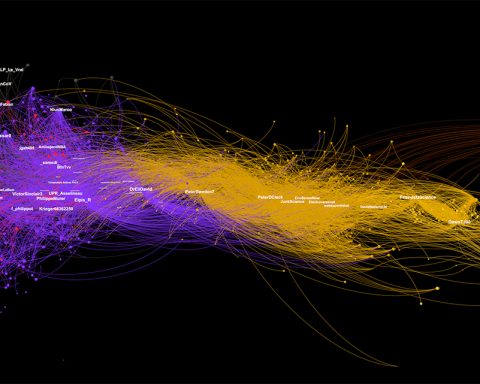

Beyond that, it is the concentration that we observe in the digital markets around a few leaders that raises questions. Such concentration is the natural result of these services, the success of which depends on important economies of scale and powerful network effects (when the usage value of a digital service increases with the number of users).

These two factors quickly lead to a third effect: the single-homingThis "locks" the consumer into the exclusive use of a single service. When a digital offer reaches a certain level of performance, users - both providers and demanders - have little interest in turning to a competing offer, when it exists! This trend could be summed up in one simple question, which can be applied to almost all digital markets: why would I use a service other than the one offered by the leader if the performance of the service is based precisely on the number of users? For example, whether you are a traveller or a driver, choosing a VTC application that competes with Uber will reduce your utility wherever Uber is dominant: on average, you will have fewer errands or have to wait longer before making a trip.

Illusionary competition

In this game of conquest of digital spaces, no other players have distinguished themselves as brilliantly as GAFAM and BATX (their Chinese counterparts). And the free nature of the services offered has undoubtedly contributed to this: it has attracted a significant number of users to the point of creating the conditions for a (near) natural monopoly.

Why not enjoy unlimited reading of UP'? Subscribe from €1.90 per week.

Barring technological disruption, it is now illusory to want to compete with Google, Facebook or Amazon (to name but a few). The entry ticket would be colossal and the delay in exploiting qualified data would be abyssal. The cases of Bing, with its "confidential" market shares, but also the Windows phoneThe fact that it is not enough to have the financial means and technical capacity to enter these markets is now buried. Network effects, user routines, and the commercial choices of the complementers (especially application developers) are all particularly tight barriers to entry.

In short, free access is the basis for audience acquisition which, in turn, will generate ripple effects to the point of creating near monopolies on all the multifaceted marketsThe aim of the project is to create an environment where several categories of actors can meet. The difficulty for competition authorities seeking to determine a possible abuse of a dominant position lies in the fact that not all monopolies are to be foughtSome of them are of course the most efficient market structures. As reported to the GAFAM, the question is all the more complex because their strategies have on the competition of the ambivalent effects.

In a sense, the digital giants are building a high-performance offer and offering many complementary players access to a colossal market. Rovio's Angry Birds game could not have known the same thing. success without the global visibility afforded by the Android (Play Store) and Apple (App Store) application stores, nor the technical support for mobile terminals and operating systems.

Eviction strategies

But conversely, these same giants have an expansionist strategy (before becoming commercial empires, Alphabet started with a search engine; Amazon with an online library) which can result in strategies to evict "third party financiers". These can take the form of unilateral price increases sometimes difficult to support, such as Google's mapping service, which has increased 14-fold for businesses in mid-2018. These giants may even choose to compete head-on with these third-party financiers to oust them. When, for example, Amazon decides to source to own of the products formerly only offered on its marketplace, Jeff Bezos' platform clearly shows the way out to independent sellers who offer these products. They can continue to offer them on the marketplace, but it is an illusion that they can compete with Amazon.

At the same time, the digital giants are particularly active on the acquisition front. The critics Such operations see it as a means of capturing early on innovations likely to compete with them in the long run. However, two arguments can be put forward against them: firstly, being bought out by one of the GAFAMs is very often the only way to ensure that the company will be able to compete in the long term.strategic focusAnd would Instagram have become Instagram without the technological and commercial support of Facebook? A real puzzle...

Finally, it is not so much business practices or pricing strategies that have changed with digital, but rather the speed with which (near) monopolies with little challenge have emerged, taking full advantage of digital to extend their market power on both a sectoral and geographical basis. Yet, how can we regulate firms whose technological boundaries and activities are constantly changing and whose natively globalized activities cannot be confined to a given territory? Is it possible to sanction them, or even to dismantleon the pretext that they would have annihilated any form of competition? It would be to disregard the fierce competition that these giants - and the BATXs - engage themselves in markets as diverse as the cloud, online advertising, streaming, or even the smart city and the autonomous vehicle.

What about the consumer in all this?

This regulation is made all the more complicated by the fact that the consumer must also be included in the equation, since safeguarding his interests is an integral part of the mission assigned to the competition authorities. In this field, one reproach can mainly be levelled at the domination exercised by the GAFAMs: the façade free of charge, against the exploitation of personal data. However, neither the multiplication of awareness-raising campaigns nor the implementation of mechanisms as visible as the DPMR have, for the time being, had the slightest impact on consumer choice. Facebook did suffer some losses in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, but remains ultra-dominant. Qwant remains in the shadow of the giant Google, and connected objects, sometimes very intrusive, continue to flow in the millions. Does this mean that the consumer prefers the raw performance of the service to the respect of his privacy?

By extending their reach and customer knowledge (via data mining), GAFAMs have succeeded in building powerful bundles - such as Google's service suite or Amazon Prime - that are popular with consumers. Condemning or regulating the GAFAMs too hastily, or even arbitrarily, would also run the risk of abandoning services whose efficiency depends on their addition within the same brand universe. And their apparent gratuitousness.

Julien PillotProfessor and Researcher in Economics and Strategy (Inseec U.) / Pr. and Associate Researcher (U. Paris Saclay), INSEEC School of Business & Economics and Frédéric MartyResearch Fellow in Law, Economics and Management, National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS)

This article is republished from The Conversation, editorial partner of UP' Magazine. Read theoriginal paper.

To fight against disinformation and to favour analyses that decipher the news, join the circle of UP' subscribers.