President Macron is right to attack fake news head-on... but the response to a media phenomenon of this magnitude is systemic and complex, and perhaps not reducible to a law targeting election periods. However, the discussion on fake news is an opportunity to bring about a long overlooked public debate about digital media and their effects on our democratic societies. It is an opportunity to rebalance the forces between the Internet of things and the Internet of citizens. It is a time when there is an urgent need to address the question of digital media of public utility, or even public service, given the "crucial resource" that the Internet has become, along with the water and air that make up our environment.

Che paradox with fake news is that it is both an epiphenomenon and a groundswell. An epiphenomenon if they are taken as propaganda or a hoax, a background phenomenon if they are seen as a signal of major democratic risks (the media being diluted in the digital world).

This is the case in France, because of the divide between those who find media literacy old-fashioned and pre-digital skills and those who see digital as so disruptive that it cannot take the media with it. This is manifested by the multiplication of distinct operators and services, the Centre for Media and Information Literacy (CLEMI) in conjunction with the Digital Education Directorate (DNE) on the one hand and the National Digital Council (CNNum) on the other. This approach is also endorsed in the Jules Ferry 3.0 report. However, it would be more judicious to emphasize the elements of continuity or convergence between these various spheres which are part of the new information cultures. They combine news, files and data - all elements at work in fake news.

The media is not digitally soluble and it remains essential to liberal democracies, struggling with the misinformation which is the basis of fake news. This one is far worse than the classic misinformation.

It is of a new kind because it is going through new media, digital platforms and their associated social network media. In the United States, where they are legally located, these platforms enjoy "carrier" status (common carrier) currently given to the Internet. They are located in the Ministry of Commerce, Transport sub-sector (not in the Ministry of Culture, which does not exist). In this way, they have managed to avoid having a public trustee status like the audiovisual sector, with public service obligations. Like most American media, they are financed by advertising. This monetization affects fake news because fake news can be financed by advertising, even when it is political propaganda.

If there is to be legislation, the question of defining the status of digital media platforms arises, even more so than that of fake news, which is one of their current emanations (others are to be expected with the trivialization of artificial intelligence). They are indeed the ones that are in the line of sight of any law. Their social, commercial and legal responsibility may be called into question, especially their current impunity and immunity. If the law qualifies them as "media", which they were forbidden to be before 2017 and the fake news crisis, they will have to assume their public obligations.

Creating a new media status for digital platforms

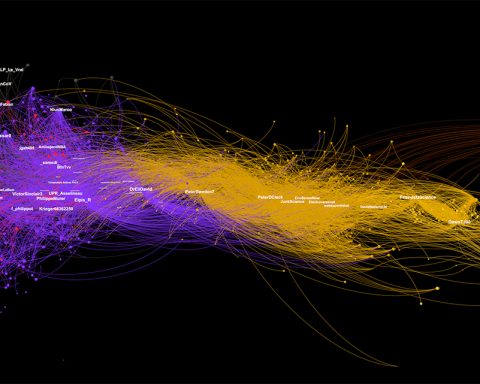

And for that we must look on the American side first if we want to hope for real change. The time is ripe because the platforms themselves want it because they are so keen on their brand image and on the revenues dependent on their audiences and communities, in connection with trust. Facebook, Google, Twitter are facing congressional hearings to explain how Russia used them during the last presidential campaign to sow "memes", basic, easily replicable pieces of information. The memes Russian people on Facebook would have reaches 126 million people...including advertisements.

This negotiation requires the demonstration that these platforms are media, requiring a specific status that respects their new potential, while remaining within the framework of freedom of expression and dissemination.

Some criteria are there: algorithms can reflect an editorial line; new audiences are made up of online communities; advertising offers a new windfall associated with the monetization of public broadcasting (Doubleclick, Adsense, etc.).

As a result, shortcomings appear in relation to the public service obligations that often accompany democratic media: the right of reply on the same medium does not exist; there is no possibility that the denial affects the same recipient communities that the fake news originally affected; the right of resale is absent; no instance can be seized other than the platform itself.

Above all, the numerical mechanisms that impact information are undervalued. Interactivity and virality impose to take into account not only the messages but also the interactions they generate (clicks, likes, posts...). In addition, there are interactions potentially extended by other tools (retweet apps and repost) as well as recommendation mechanisms, including influencers (the most followed being... the press organs themselves!).

This is not to mention the de facto monopolies, which allow Instagram to rely on the commercial and advertising power of Facebook or YouTube to call on that of Google, which multiplies the opportunities for republication and thus the impact of misinformation.

We must therefore discuss this media status with the platforms in a systemic way: in addition to content and interaction, we must take into account regulation, competition, taxation, among others. This will undoubtedly lead to a hybrid and unprecedented status, between that of carrier and that of curator.

This debate is essential because the platforms are our infomediaries

And the gigantic size of these platforms and the power we have allowed them to gain is the result of monopolies that can be toxic to democracy, which is based on informed public opinion that is brought to the ballot box.

The fundamental debate on the liability of Internet infomediaries and question their relationship to freedom of expression and online dissemination. The balance between these issues is crucial. It is not easy to manage: it is a question of information sovereignty, and the capacity of states to respond to a transborder medium. More broadly, it is a question of national digital sovereignty at a time when US-regulated media platforms have a de facto monopoly position and threaten the independence and pluralism of content and the integrity of online interactions.

Liberal instruments of self-regulation have reached their limits, particularly in relation to risk content and behaviour: the dereferencing has been put in place by the platforms; in-house assessment teams are working to close accounts, interrupt feeds, remove videos deemed unsuitable; online hate speech and forms of cyberstalking are being dealt with ad hoc, which may include blocking websites or interrupting subscriber accounts

The difficulty is all the greater in that misinformation is not illegal and it would be difficult to make it illegal with regard to political discourse, since political discourse is inherently free in a democracy. This is the whole problem of confining a law to the electoral period, as if fake news were not toxic at other times of the year: the Russian memes aim to create links and to make the public aware of the situation. to reach communities over time.

The actor who manipulates fake news can be abroad, or even be a state in the same way as France. In fact, Facebook self-designated itself as a "public curator" by closing 3,000 fake accounts in anticipation of the elections in France, to counter Russian interventions. Could a French law provide the means to bring this international issue before a national court of justice, which in fact involves two third countries, the United States (as far as digital platforms are concerned) and Russia (as far as the memes) ?

The Conseil Supérieur de l'Audiovisuel, Tour Mirabeau, Paris. P Beef Turners CSA

France is rich in instruments, poor in governance

It has the CSA, CNIL and ARCEP, among others. It can rely on the 1881 law on freedom of the press, which includes defamation... But it is true that these instruments are compartmentalized, sectorized, siloed and cannot cover transmedia and cross-border entities such as digital platforms on the Internet.

The public debate on fake news is perhaps an opportunity to think about a well-coordinated governance between these bodies. It could go through an in-depth reform of a body in crisis, following the resignation of the president and a large part of its members, the CNNum. This would be an opportunity to make it an independent and truly multi-stakeholder ethical governance body, which implies transparency, accountability and so on.

It is also a real opportunity for CLEMI to make its transformation from a simple analysis of the press, however useful it may be, to a mastery of what data do to the media. Content alone is not enough to understand the phenomenon if interactions on social networks and regulation by algorithms are not taken into account. This explains the lack of success of fact checking as the only answer to fake news. We cannot avoid this public debate and this opportunity for basic pedagogy to give French people a real general knowledge of the Internet and avoid major risks of rejection of this crucial resource.

Any law in France, in order to be effective, must coordinate its action with the transnational logic necessary for transfrontier media and increasingly interdependent software infrastructures. It cannot ignore national thinking in other European countries, whether in Germany, Sweden or elsewhere. It can benefit from taking into account the work of the high level panel on fake news by Mariya Gabriel, the new digital commissioner.

Finally, civil society, especially NGOs with a strong presence in France and at the UN, such as Article 19 and APC, are mobilising against the direct regulation of fake news. This will create tensions between the different jurisdictions, with the United States and the rest of the world in the lead (as demonstrated by the recent cancellation of the net neutrality by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). But also between regional jurisdictions such as those of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) .

In this period of hopes for the year 2018, the challenge to be overcome is to find a vision shared by liberal democracies on the strategy to follow, because otherwise the risk is to patch every new form of fake news that emerges. Above all, the risk is that of a freeze on freedom of expression and dissemination, leading to self-censorship for fear of sanctions.

The solution is multiple. It involves changing the tax system applied to media platforms and amending the laws governing competition between media. It also includes the protection and promotion of an ethical and quality journalistic system. In the medium term, it involves media and information education that is not limited to the example that is cited at each sad commemoration of the Charlie Hebdo attack.

Finally, it seems essential to open the debate on the creation of a genuine digital public service, which could enrich the new status of digital media, beyond the hybridity between carrier and curator. In order to give it real autonomy and quality resources, it could benefit from long-term funding from a levy on the revenues earned by digital media platforms in France. It is at this price that we will be able to find various democratic means to tip the balance towards the reasoned practice of information and the search for the reality of the facts, if not the truth.

Divina Frau-MeigsProfessor of Information and Communication Sciences, Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris 3 - USPC

The original text of this article was published on The Conversationeditorial partner of UP'.