The names of these promising drugs to treat COVID-19 patients are beginning to become known to the public: Remdesivir, Ritonavir, Lopinavir and of course the most talked about, Chloroquine. These four promising treatments will be the subject of a large global study conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO). Another study on the same substances (excluding Chloroquine) has just been launched by Europe with Inserm as coordinator. These two mega-studies are a first in terms of their size, the nature of their deployment in the midst of an epidemic crisis and the cooperation they demonstrate between scientists from all countries.

Could any of these drugs save patients with VIDOC-19 from serious harm or death? The World Health Organization (WHO) has announced a large global trial, called SOLIDARITY, to find out if any of them can treat infections with the new coronavirus for this dangerous respiratory disease. This is an unprecedented effort - a coordinated and comprehensive effort to rapidly collect sound scientific data during a pandemic. The study, which could involve several thousand patients in dozens of countries, has been designed to be as simple as possible so that even hospitals overwhelmed by an avalanche of patients with COVID-19 can participate.

With about 15% of COVID-19 patients suffering from serious illnesses and hospitals overwhelmed, treatment is desperately needed. That's why, rather than creating compounds from scratch that could take years to develop and test, researchers and public health agencies are looking to redirect drugs already approved for other diseases that are known to be largely safe. They are also looking at unapproved drugs that have worked well in animal studies with the other two deadly coronaviruses, which cause Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MRS).

Drugs that slow or kill the new coronavirus, scientifically known as SARS-CoV-2, could save the lives of seriously ill patients but could also be given prophylactically to protect health care workers and others at high risk of infection. The treatments could also reduce the time patients spend in intensive care units, freeing up critical hospital beds.

Tests conducted in record time

Scientists have proposed dozens of existing compounds for testing, but WHO is focusing on the four most promising treatments: an experimental antiviral compound, remesivir; the antimalarial drugs chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and this same combination plus interferon beta, an immune system messenger that can help paralyze viruses. Some data on their use in patients treated with COVID-19 have already been published - the HIV combination failed in a small study in China - but the WHO believes that a large trial with a wider range of patients is warranted.

It will be easy to register topics for SOLIDARITY. When a person with a confirmed case of COVID-19 is deemed eligible, the physician can enter the patient's data on a dedicated WHO website, including any underlying conditions that could alter the course of the disease, such as diabetes or HIV infection. The participant must sign an informed consent form that is scanned and sent electronically to WHO. Once the physician has indicated which drugs are available in his or her hospital, the website randomly selects the patient for one of the available drugs or for local standard care for COVID-19.

" After that, no further action or documentation is necessary. " says Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo, a physician in the WHO Department of Vaccines and Biologicals. Doctors will note the day the patient left the hospital or died, the length of stay in the hospital and whether the patient needed oxygen or ventilation, she says. " That's it."

Balancing scientific rigour and speedThe design is not double-blind, the gold standard of medical research, so there could be placebo effects in patients knowing they have received a drug candidate. But the WHO says it has had to balance scientific rigour with speed. The idea for SOLIDARITY came up less than two weeks ago, says Dr Henao-Restrepo, and the agency hopes to have documentation and data management centres in place by next week. " We're doing this in record time, " she says.

It will be important to get answers quickly, to try to find out what works and what doesn't work. We believe that the best way to do this is to use random evidence. Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University's Langone Medical Center, says he likes the design of the study. " No one wants to penalize the front-line caregiver who is overwhelmed and taking risks anyway, " he says. Hospitals that are not overburdened could record more data on disease progression, such as tracking the level of viruses in the body, Caplan suggests. But from a public health perspective, the simple results that WHO is trying to measure are the only relevant ones at the moment says virologist Christian Drosten of the Charité University Clinic in Berlin: " We don't know enough about this disease to know what it means when the viral load in the throat, for example, drops. ".

European Joint Trial

On Sunday, the French National Institute for Medical Research (INSERM) announced that it will coordinate a complementary trial in Europe, called DISCOVERY, which will follow the example of the WHO and include 3,200 patients from at least 7 countries, including 800 from France. This trial will test the same drugs as the WHO. In its French component, the trial will include at least 800 patients with severe forms of coronavirus. In total, some 3,200 European patients will be included in the study involving Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Germany and Spain. The data obtained will be shared with the WHO.

Other countries or host groups could also organize complementary studies, according to Ana Maria Heneo Restrepo. They are free to make additional measurements or observations, for example on virology, blood gases, chemistry, and lung imaging. " Although well-organized follow-up studies on the natural history of the disease or the effects of experimental treatments may be useful, they are not fundamental requirements, " she says.

The list of drugs to be tested first was drawn up for WHO by a group of scientists who have been assessing the evidence for candidate therapies since January, Restrepo explains. The group selected the drugs that were most likely to be effective, had the most safety data from previous use, and were likely to be available in sufficient quantities to treat a significant number of patients if the trial showed they were effective.

- READ IN UP' : The race for vaccines and treatments is accelerating

The treatments that SOLIDARITY and DISCOVERY will test:

Remdesivir

The new coronavirus gives this compound a second chance to shine. Originally developed by Gilead to fight Ebola and related viruses, remdesivir stops viral replication by inhibiting a key viral enzyme, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase.

Researchers tested the drug last year during last year's Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo, along with three other treatments. It showed no effect. But the enzyme it targets is similar in other viruses, and in 2017, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill showed in test tubes and animals that the drug can inhibit the coronaviruses that cause SARS and MERS.

The first COVID-19 patient diagnosed in the United States - a young man from Snohomish County, Washington - was given a comeback when his condition worsened and improved the next day, according to a case report published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). A patient in California who had been treated for depression - and whose doctors thought he might not survive - also recovered.

Such evidence from individual cases does not prove that a drug is safe and effective. Nevertheless, according to the drugs in the SOLIDARITY trial, " remdesivir is most likely to be used clinically, " says Jiang Shibo of Fudan University in Shanghai, China, which has long been working on coronavirus treatments. Jiang particularly appreciates the fact that high doses of the drug can be administered without causing toxicity.

However, it can be much more potent if given at the onset of an infection, like most other drugs, says Stanley Perlman, a coronavirus researcher at the University of Iowa. " What you really want to do is give a drug like this to people who present with mild symptoms, " he says. " And you can't do that because it's a [intravenous] drug, it's expensive and 85 out of 100 people don't need it. ".

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine

It's the most talked-about drug, even for people who aren't doctors. This was the case, at a press conference on Friday when President Donald Trump called chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine " game changer" . " I feel good about it." he said in his singular rhetoric. His remarks led to a rush on anti-malarial drugs that had been going on for decades.

The WHO scientific group that designed SOLIDARITY had originally decided to leave the duo out of the trial but changed its mind at a meeting in Geneva on March 13 because the drugs " have received significant attention "in many countries, according to the report of a WHO working group that examined the potential of the drugs. Widespread interest prompted " the need to examine emerging evidence to inform a decision on its potential role."

The data available is meagre. Drugs work by decreasing the acidity of endosomes, compartments inside cells that they use to ingest external material and that some viruses can co-opt to enter a cell. But the main route of entry for SARS-Cov-2 is different, using its so-called spike protein to bind to a receptor on the surface of human cells. Cell culture studies have suggested that chloroquines have some activity against SARS-CoV-2, but the doses needed are generally high and could cause severe toxicity.

Encouraging results from cellular studies of chloroquines against two other viral diseases, dengue fever, and chikungunya, have not yielded convincing results in humans in randomized clinical trials. And non-human primates infected with chikungunya had even worse results when given chloroquine. " Researchers have tried this drug virus after virus, and it has never worked in humans. The dose needed is simply too high, " says Susanne Herold, an expert in lung infections at the University of Giessen, Germany.

The results in patients treated with COVID-19 are unclear. Chinese researchers who claim to have treated more than 100 patients with chloroquine touted its benefits in a letter published in BioScience, but the data behind this claim have not been published. In total, more than 20 COVID-19 studies in China have used chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, the WHO notes, but their results have been difficult to obtain. " WHO engaged with Chinese colleagues at the Geneva mission and was assured of better collaboration; however, no data were shared on chloroquine studies. ".

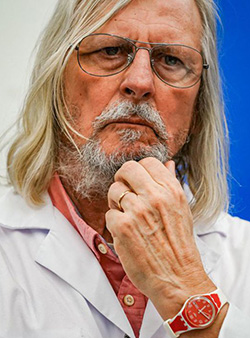

The French team of the now-famous Professor Didier Raoult published a study in which doctors treated 20 COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine. They concluded that the drug significantly reduced the viral load in nasal swabs. But this was not a randomized controlled trial and it did not report clinical outcomes such as deaths. In a guideline published Friday, the American Society of Critical Care Medicine said " there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation on the use of chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine in critically ill adults with COVID-19 ".

These reservations did not prevent Professor Raoult from launching tests directly on patients at the IHU in Marseille, even before the publication of the results of the European clinical trial that began this Sunday.

Professor Philippe Parola, head of the Infectious Diseases Department at the IHU in Marseilles, justifies this decision: " We must not wait for patients to get worse and arrive in intensive care to see what my fellow resuscitators are experiencing, i.e. a massive influx of patients who are often elderly and at a very advanced stage of the disease, " he told France Info. Professor Parola also provided new data on chloroquine as part of a treatment against coronavirus. According to him, the tests should combine chloroquine "with an antibiotic called azithromycin". " In the first licensed trial we did, the combination of chloroquine and azithromycin meant that by six days the small number of patients who received this treatment had no detectable virus, meaning they were no longer contagious, " he said. In France, the only French manufacturer of chloroquine is currently in the midst of work to supply testing facilities.

However, there are opinions that hydroxychloroquine, in particular, could do more harm than good. This drug has many side effects and may, in rare cases, lead to heart problems. Because people with heart problems are at greater risk of serious COVID-19, this is a concern, says David Smith, an infectious disease physician at the University of California, San Diego. " It's a red flag, but we still need to test it, " he says.

Ritonavir/lopinavir

This combination of drugs, sold under the brand name Kaletra, was approved in the United States in 2000 to treat HIV infections. Abbott Laboratories developed lopinavir specifically to inhibit HIV protease, an important enzyme that breaks a long chain of proteins into peptides when assembling new viruses. Because lopinavir is rapidly broken down in the human body by our own proteases, it is administered with low levels of ritonavir, another protease inhibitor, which allows lopinavir to persist longer.

This combination may also inhibit the protease of other viruses, particularly coronaviruses. It has been shown to be effective in marmosets infected with the MERS virus, and has also been tested in patients with SARS and MERS, although the results of these trials are ambiguous.

However, the first trial with COVD-19 was not encouraging. Doctors in Wuhan, China, gave 199 patients two lopinavir/ritonavir pills twice a day in addition to usual care, or usual care alone. There was no significant difference between the groups, they reported in the March 15 NEJM . But the authors warn that the patients were very ill - more than one-fifth died - and that the treatment may have been given too late to help them. Although the drug is generally safe, it can interact with drugs usually given to seriously ill patients, and doctors warned that it could cause significant liver damage.

Ritonavir/lopinavir + interferon beta

SOLIDARITY will also have a component that combines the two antivirals with interferon beta, a molecule involved in the regulation of inflammation in the body that has also shown an effect in marmosets infected with MERS. A combination of these three drugs is currently being tested in MERS patients in Saudi Arabia in the first randomized controlled trial for this disease.

But the use of beta interferon on patients with severe COVID-19 could be risky, warns Professor Susanne Herold. " If given at an advanced stage of the disease, it could easily lead to more severe tissue damage instead of helping patients, "she warns.

Thousands of patient guinea pigs

The design of the SOLIDARITY test can be modified at any time. A Global Data Security Monitoring Board will review the interim results at regular intervals and decide whether any of the members of the quartet have a clear effect or can be dropped because they clearly do not. Several other drugs, including the anti-influenza drug favipiravir, produced by the Japanese company Toyama Chemical, could be added to the trial.

In order to obtain robust study results, several thousand patients will likely need to be recruited," explains Henao-Restrepo. Argentina, Iran, South Africa and several other non-European countries have already signed on. WHO also hopes to conduct a prevention trial to test drugs that can protect health workers from infection, using the same basic protocol, says Henao-Restrepo.

The European counterpart of the DISCOVERY trial, will recruit patients from France, Spain, the UK, Germany and the Benelux countries, according to an INSERM press release issued today. The trial will be led by Florence Ader, a researcher in infectious diseases at the Lyon University Hospital Center.

Doing rigorous clinical research during an epidemic is always a challenge, says Dr. Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo, but it's the best way to make progress against the virus.

Source : Science